J Korean Med Sci.

2022 Feb;37(6):e49. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e49.

Workload of Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Outbreak in Korea: A Nationwide Survey

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyungpook National University, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University Chilgok Hospital, Daegu, Korea

- 3Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyungpook National University, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, Korea

- 4Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Internal Medicine, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Internal Medicine, Pusan National University School of Medicine and Medical Research Institute, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea

- 7Department of Internal Medicine, Konkuk University School of Medicine, Konkuk University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 8Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Jeju National University, Jeju, Korea

- 9Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea

- 10Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, National Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 11Department of Infectious Diseases, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea

- 12Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 13Hospital Infection Control Team, Daegu Medical Center, Daegu, Korea

- 14Division of Respiratory Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Masan Medical Center, Changwon, Korea

- 15Department of Internal Medicine, Andong Medical Center, Andong, Korea

- 16Department of Internal Medicine, Konyang University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea

- KMID: 2526037

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e49

Abstract

- Background

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is ongoing, heavy workload of healthcare workers (HCWs) is a concern. This study investigated the workload of HCWs responding to the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea.

Methods

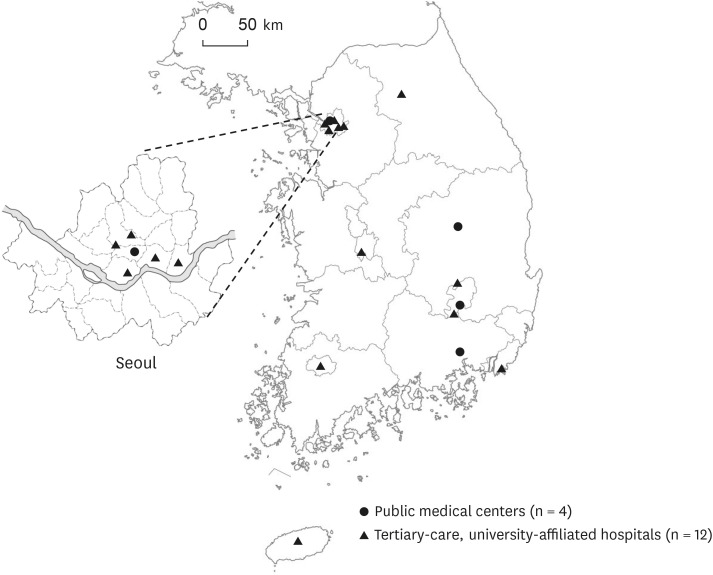

A nationwide cross-sectional survey was conducted from September 16 to October 15, 2020, involving 16 healthcare facilities (4 public medical centers, 12 tertiary-care hospitals) that provide treatment for COVID-19 patients.

Results

Public medical centers provided the majority (69.4%) of total hospital beds for COVID-19 patients (n = 611), on the other hand, tertiary care hospitals provided the majority (78.9%) of critical care beds (n = 57). The number of beds per doctor (median [IQR]) in public medical centers was higher than in tertiary care hospitals (20.2 [13.0, 29.4] versus 3.0 [1.3, 6.6], P = 0.006). Infectious Diseases physicians are mostly (80%) involved among attending physicians. The number of nurses per patient (median [interquartile range, IQR]) in tertiarycare hospitals was higher than in public medical centers (4.6 [3.4–5] vs. 1.1 [0.8–2.1], P =0.089). The median number of nurses per patient for COVID-19 patients was higher than the highest national standard in South Korea (3.8 vs. 2 for critical care). All participating healthcare facilities were also operating screening centers, for which a median of 2 doctors, 5 nurses, and 2 administrating staff were necessary.

Conclusion

As the severity of COVID-19 patients increases, the number of HCWs required increases. Because the workload of HCWs responding to the COVID-19 outbreak is much greater than other situations, a workforce management plan regarding this perspective is required to prevent burnout of HCWs.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), weekly epidemiological update. Updated 2022. Accessed March 29, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/m .2. Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Updated 2022. Accessed March 30, 2021. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/ .3. Oh J, Lee JK, Schwarz D, Ratcliffe HL, Markuns JF, Hirschhorn LR. National Response to COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea and lessons learned for other countries. Health Syst Reform. 2020; 6(1):e1753464. PMID: 32347772.4. Wi YM, Lim SJ, Kim SH, Lim S, Lee SJ, Ryu BH, et al. Response system for and epidemiological features of COVID-19 in Gyeongsangnam-do Province in South Korea. Clin Infect Dis. 2021; 72(4):661–667. PMID: 32672789.5. Sun S, Xie Z, Yu K, Jiang B, Zheng S, Pan X. COVID-19 and healthcare system in China: challenges and progression for a sustainable future. Global Health. 2021; 17(1):14. PMID: 33478558.6. Son KB, Lee TJ, Hwang SS. Disease severity classification and COVID-19 outcomes, Republic of Korea. Bull World Health Organ. 2021; 99(1):62–66. PMID: 33658735.7. Park SY, Kim B, Jung DS, Jung SI, Oh WS, Kim SW, et al. Psychological distress among infectious disease physicians during the response to the COVID-19 outbreak in the Republic of Korea. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):1811. PMID: 33246426.8. Choi JY. COVID-19 in South Korea. Postgrad Med J. 2020; 96(1137):399–402. PMID: 32366457.9. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(25):2451–2460. PMID: 32412710.10. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Updated 2021. Accessed Oct 1, 2021. https://www.hira.or.kr/eng/main.do2021 .11. Jang Y, Park SY, Kim B, Lee E, Lee S, Son HJ, et al. Infectious diseases physician workforce in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(49):e428. PMID: 33350186.12. Kwon S. Thirty years of national health insurance in South Korea: lessons for achieving universal health care coverage. Health Policy Plan. 2009; 24(1):63–71. PMID: 19004861.13. Yoo KJ, Kwon S, Choi Y, Bishai DM. Systematic assessment of South Korea’s capabilities to control COVID-19. Health Policy. 2021; 125(5):568–576. PMID: 33692005.14. Cho Y, Chung H, Joo H, Park HJ, Joh HK, Kim JW, et al. Comparison of patient perceptions of primary care quality across healthcare facilities in Korea: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020; 15(3):e0230034. PMID: 32155199.15. Kim J, Kim S, Lee E, Kwon H, Lee J, Bae H. The effect of the reformed nurse staffing policy on employment of nurses in Korea. Nurs Open. 2021; 8(5):2850–2856. PMID: 33838018.16. Park SH. Personal protective equipment for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Chemother. 2020; 52(2):165–182. PMID: 32618146.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Burnout among Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic

- Burnout and Its Associated Factors Among COVID-19 Frontline Healthcare Workers

- Hospital Infection Control Practice in the COVID-19 Era: An Experience of University Affiliated Hospital

- An Outbreak of Campylobacter Jejuni Involving Healthcare Workers Detected by COVID-19 Healthcare Worker Symptom Surveillance

- Factors Affecting Fear of COVID-19 Infection in Healthcare Workers in COVID-19 Dedicated Teams: Focus on Professional Quality of Life