J Dent Rehabil Appl Sci.

2021 Mar;37(1):31-38. 10.14368/jdras.2021.37.1.31.

Heme effects of hemin on growth of peridontopathogens

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Preventive Dentistry, College of Dentistry, Dankook University, Cheonan, Republic of Korea

- 2Department of Oral Microbiology and Immunology, College of Dentistry, Dankook University, Cheonan, Republic of Korea

- KMID: 2525976

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14368/jdras.2021.37.1.31

Abstract

- Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate effect of heme on periodontopathogens. Materials and Methods: The experiment was performed using 7 types of anaerobic bacteria present in the periodontal pocket. The bacteria were cultured using suitable medium in an anaerobic condition with or without hemin, and the growth of the bacteria was measured every 6 hours by a spectrophotometer.

Results

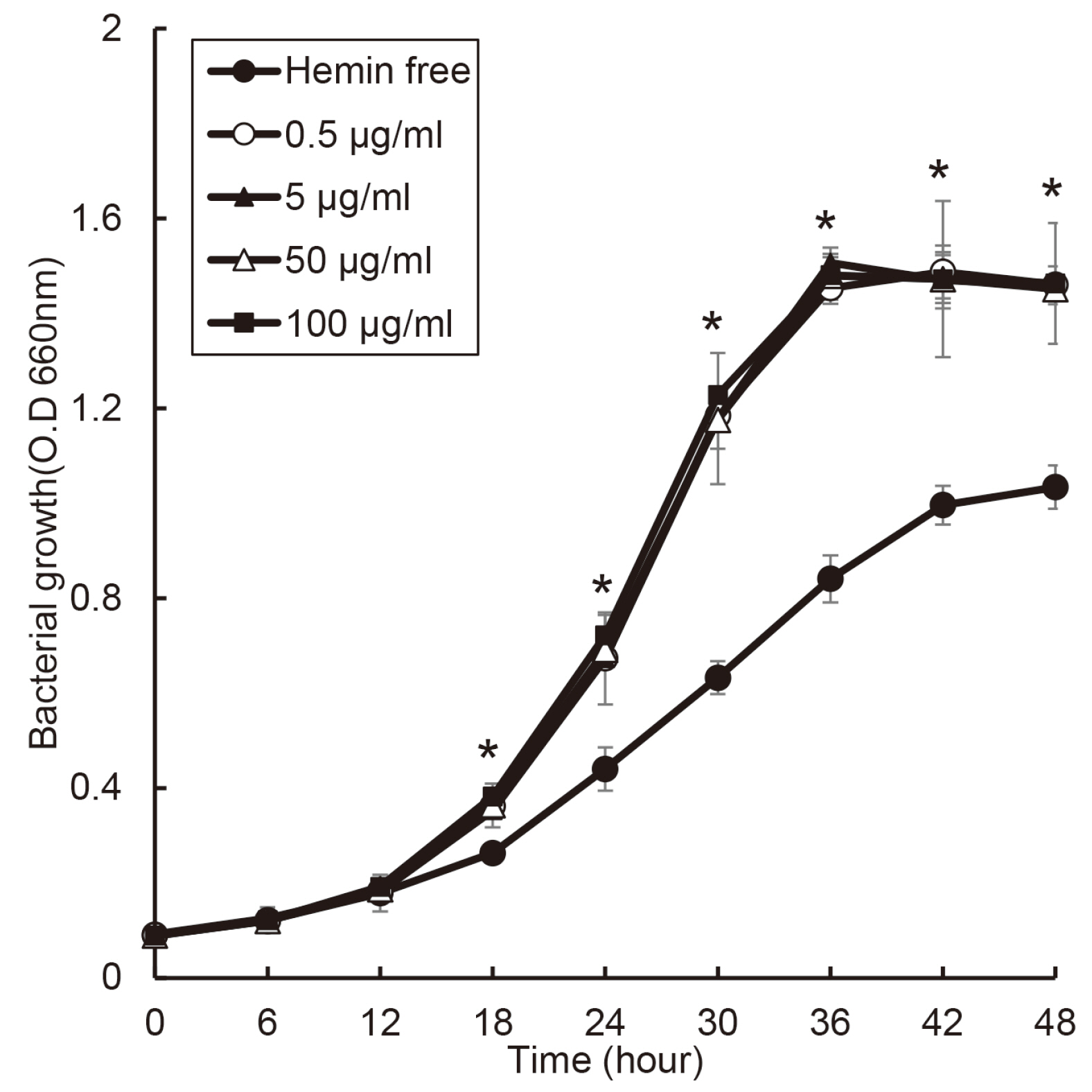

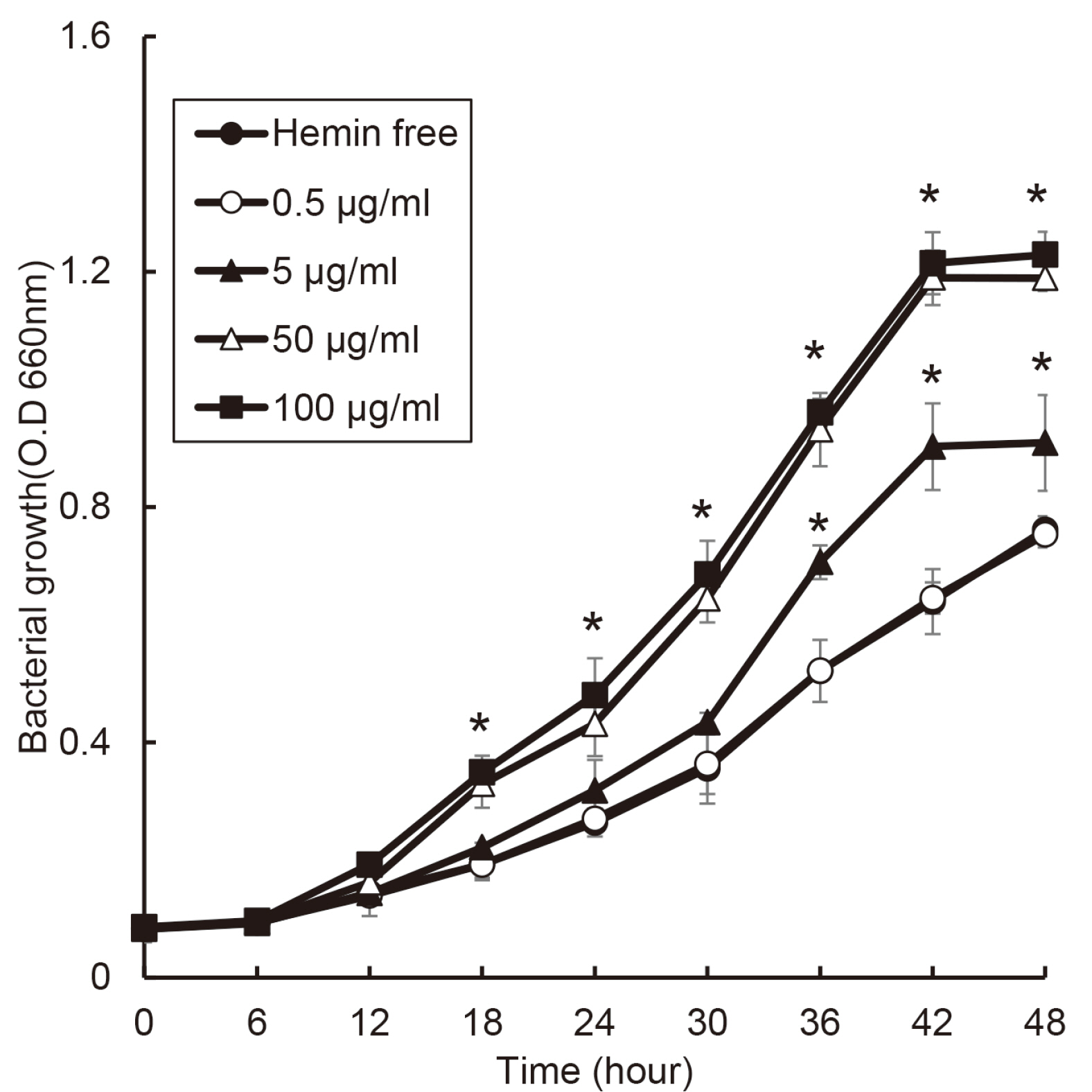

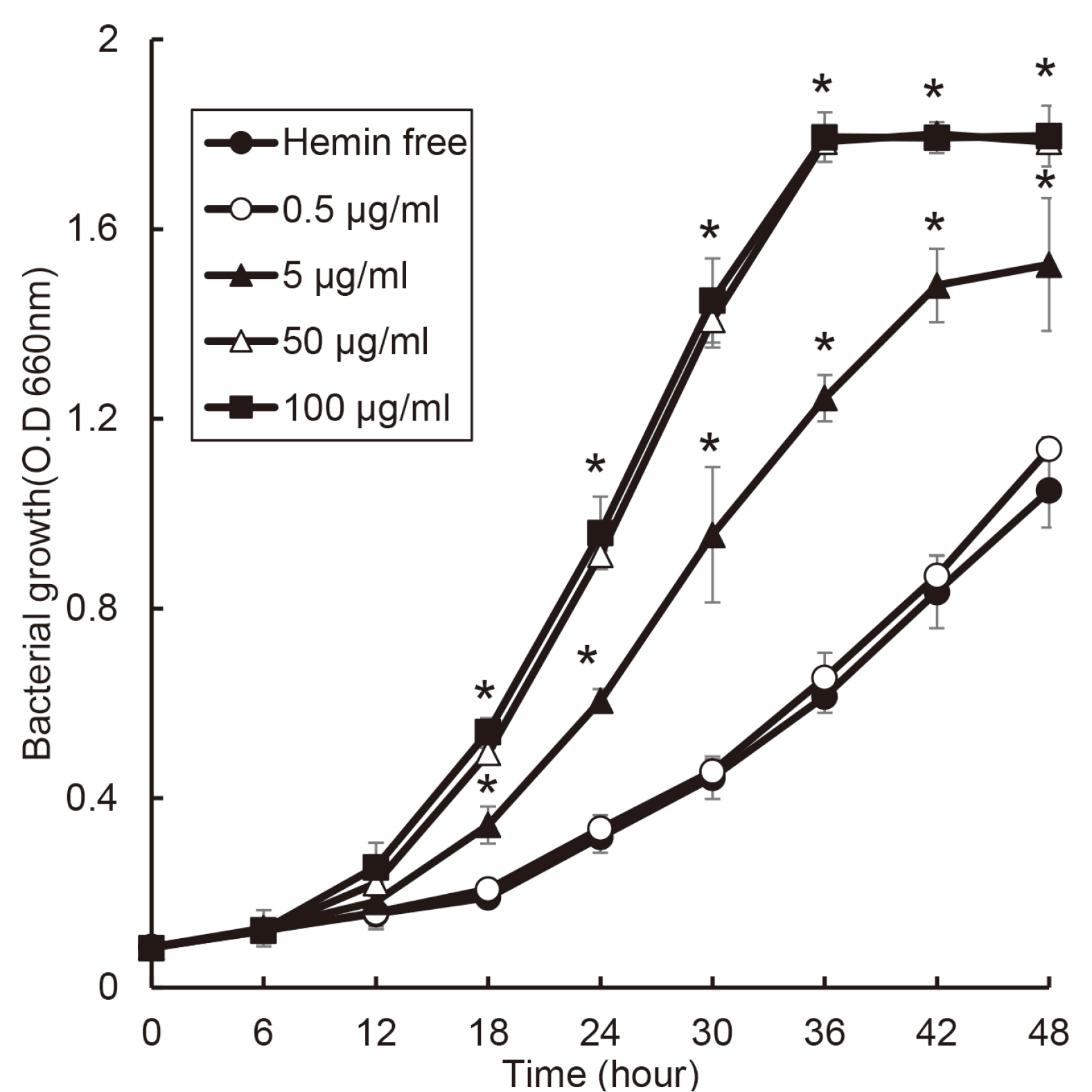

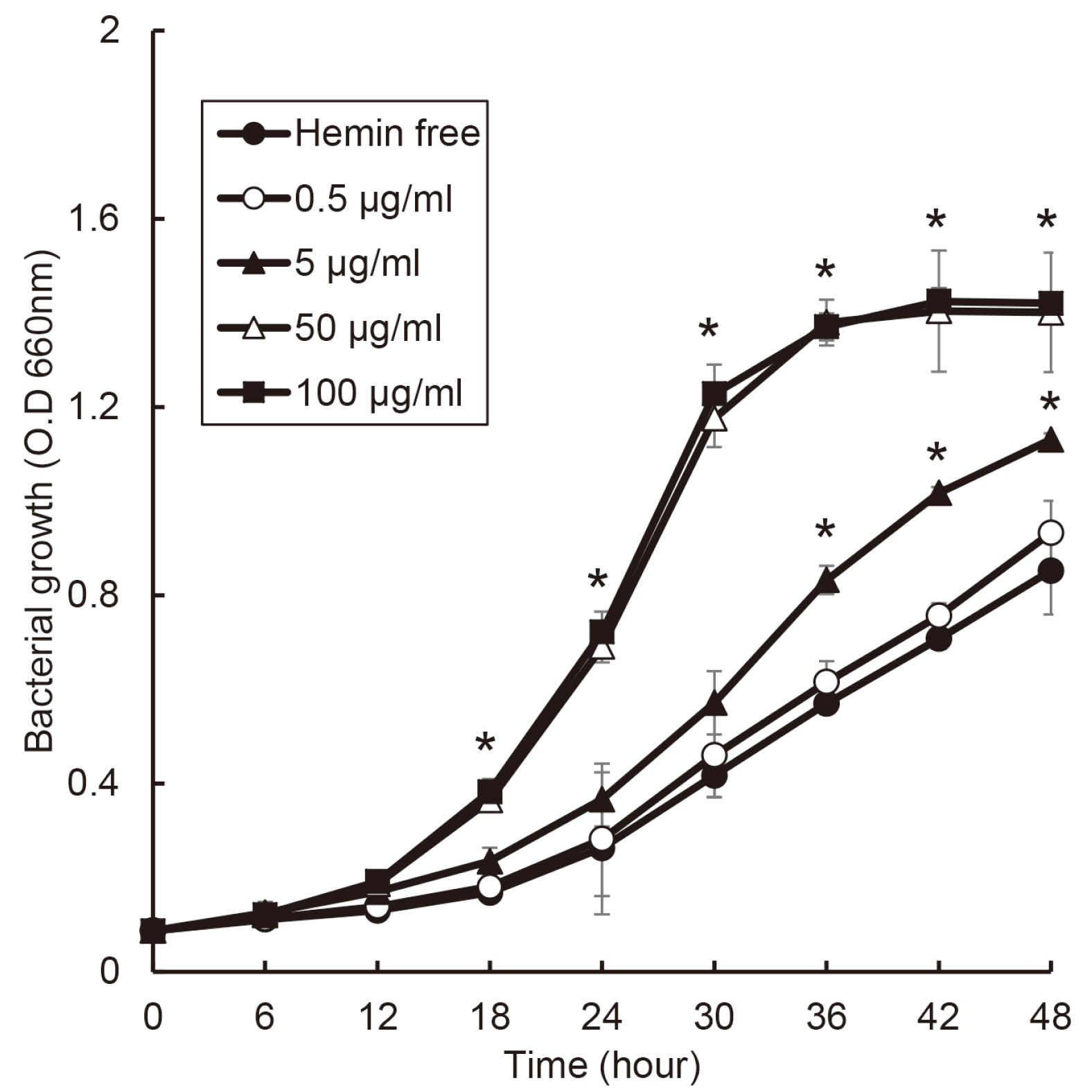

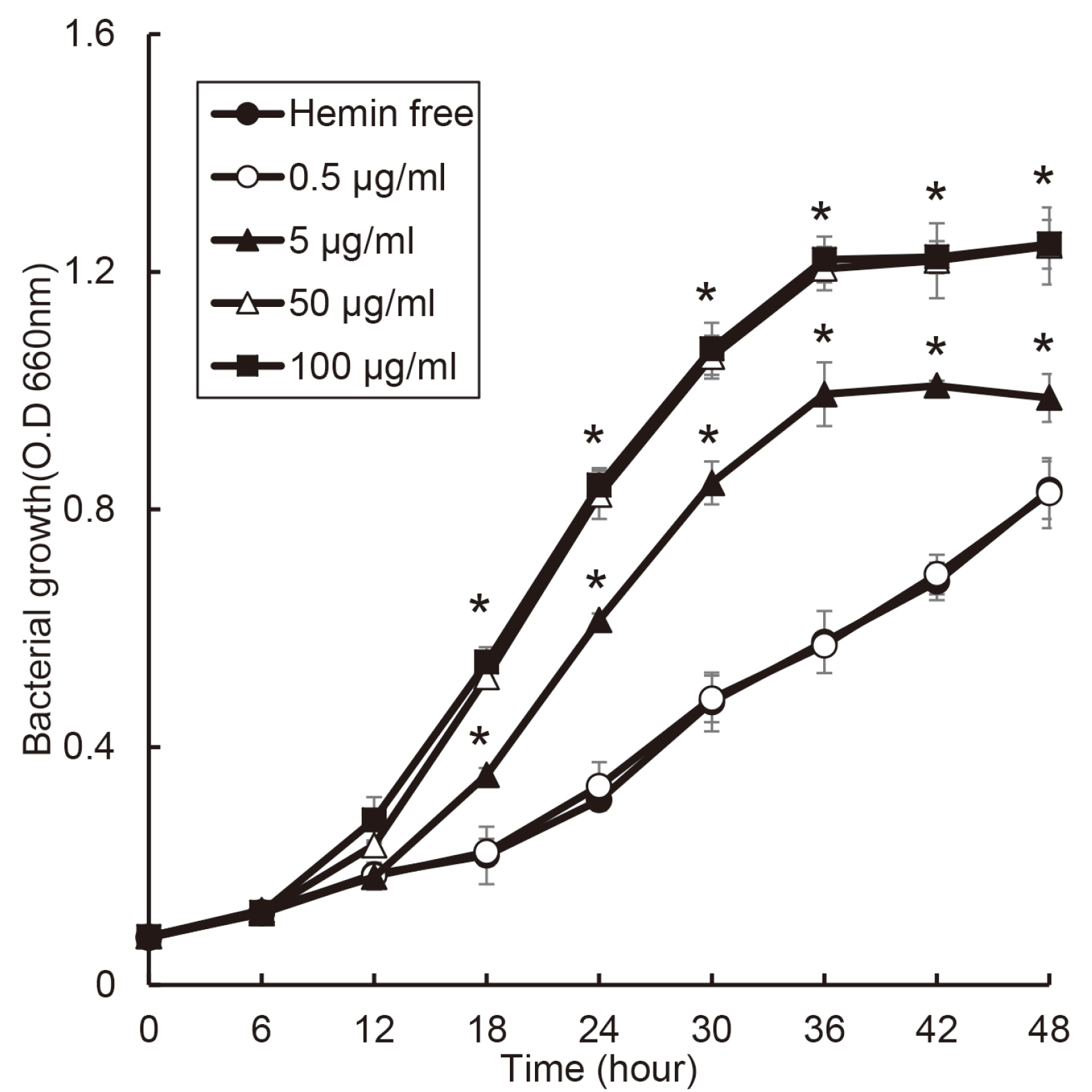

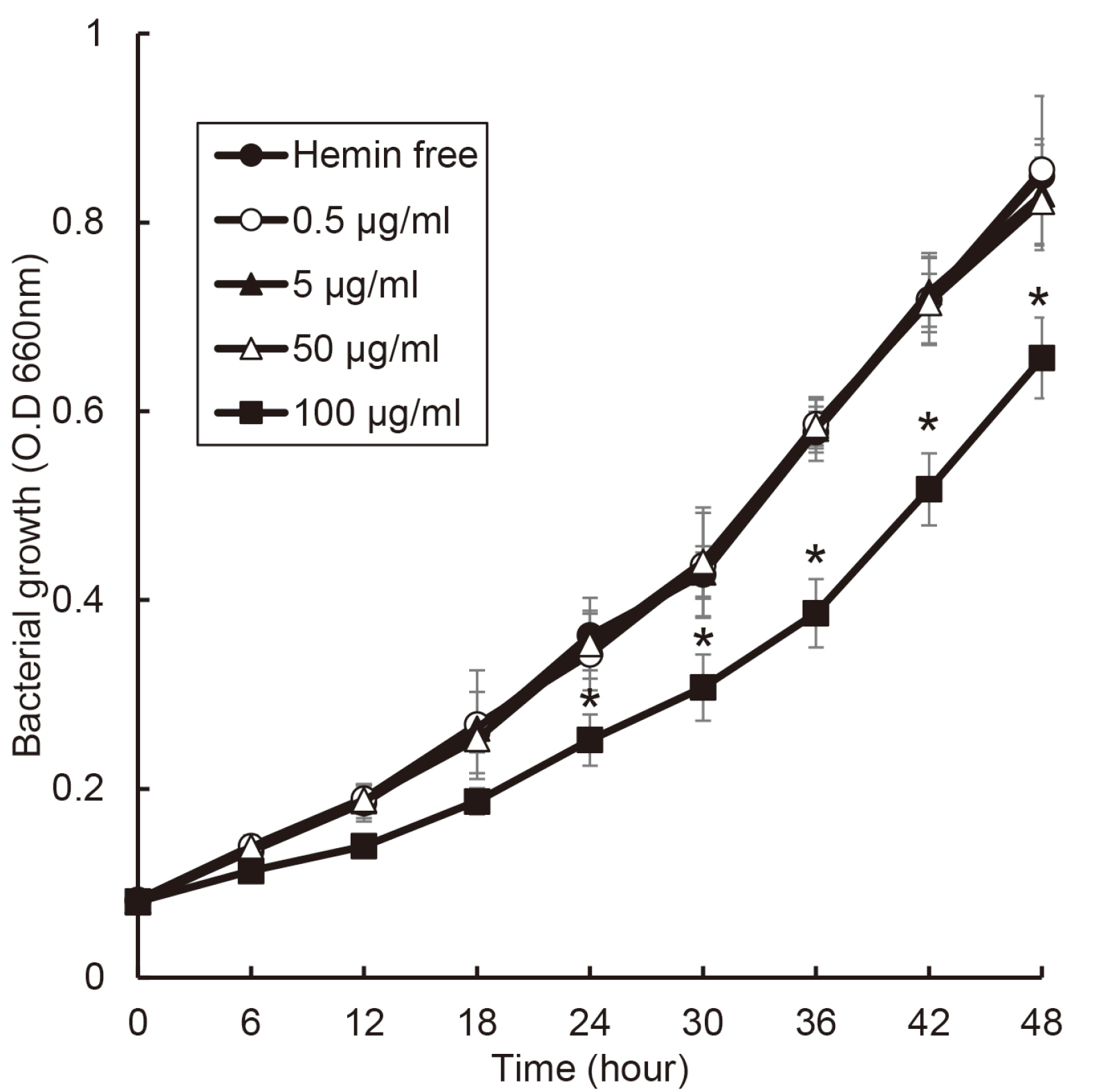

the growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis was different only by the presence or absence of hemin. The growth of other periodontopathogens except Treponema denticola was different in a hemin concentration-dependent manner. The growth of T. denticola was interfered by hemin.

Conclusion

Heme may be a factor that leads dysbiosis in the microbial ecosystem of the subgingival plaque and thereby promote a periodontitis-causing environment.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Dahlén GG. 1993; Black-pigmented gram-negative anaerobes in periodontitis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 6:181–92. DOI: 10.1016/0928-8244(93)90089-M. PMID: 8518755.2. Socransky SS. 1977; Microbiology of periodontal disease - present status and future considerations. J Periodontol. 48:497–504. DOI: 10.1902/jop.1977.48.9.497. PMID: 333085.3. O'Brien-Simpson NM, Veith PD, Dashper SG, Reynolds EC. 2004; Antigens of bacteria associated with periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 35:101–34. DOI: 10.1111/j.0906-6713.2004.003559.x. PMID: 15107060.4. Marsh PD. 1994; Microbial ecology of dental plaque and its significance in health and disease. Adv Dent Res. 8:263–71. DOI: 10.1177/08959374940080022001. PMID: 7865085.5. Listgarten MA. 1988; The role of dental plaque in gingivitis and periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 15:485–7. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.1988.tb01019.x. PMID: 3053789.6. Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. 2012; The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 10:717–25. DOI: 10.1038/nrmicro2873. PMID: 22941505. PMCID: PMC3498498.7. Wijnsma KL, Veissi ST, de Wijs S, van der Velden T, Volokhina EB, Wagener FADTG, van de Kar NCAJ, van den Heuvel LP. 2020; Heme as Possible Contributing Factor in the Evolvement of Shiga-Toxin Escherichia coli Induced Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome. Front Immunol. 11:547406. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.547406. PMID: 33414780. PMCID: PMC7783363.8. Muller-Eberhard U, Fraig M. 1993; Bioactivity of heme and its containment. Am J Hematol. 42:59–62. DOI: 10.1002/ajh.2830420112. PMID: 8416298.9. Chaudhry SR, Hafez A, Rezai Jahromi B, Kinfe TM, Lamprecht A, Niemela M, Muhammad S. 2018; Role of Damage Associated Molecular Pattern Molecules (DAMPs) in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (aSAH). Int J Mol Sci. 19:2035. DOI: 10.3390/ijms19072035. PMID: 30011792. PMCID: PMC6073937.10. Liu X, Olczak T, Guo HC, Dixon DW, Genco CA. 2006; Identification of amino acid residues involved in heme binding and hemoprotein utilization in the Porphyromonas gingivalis heme receptor HmuR. Infect Immun. 74:1222–32. DOI: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1222-1232.2006. PMID: 16428772. PMCID: PMC1360300.11. Rouault TA. 2004; Microbiology. Pathogenic bacteria prefer heme. Science. 305:1577–8. DOI: 10.1126/science.1102975. PMID: 15361615.12. Al-Qutub MN, Braham PH, Karimi-Naser LM, Liu X, Genco CA, Darveau RP. 2006; Hemin-dependent modulation of the lipid A structure of Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 74:4474–85. DOI: 10.1128/IAI.01924-05. PMID: 16861633. PMCID: PMC1539574.13. Lee HR, Rhyu IC, Kim HD, Jun HK, Min BM, Lee SH, Choi BK. 2011; In-vivo-induced antigenic determinants of Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum. Mol Oral Microbiol. 26:164–72. DOI: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2010.00594.x. PMID: 21375706.14. Yu F, Anaya C, Lewis JP. 2007; Outer membrane proteome of Prevotella intermedia 17: identification of thioredoxin and iron-repressible hemin uptake loci. Proteomics. 7:403–12. DOI: 10.1002/pmic.200600441. PMID: 17177252.15. Aguilera O, Andrés MT, Heath J, Fierro JF, Douglas CW. 1998; Evaluation of the antimicrobial effect of lactoferrin on Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia and Prevotella nigrescens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 21:29–36. DOI: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01146.x. PMID: 9657318.16. Liu LY, McGreor N, Wong BK, Butt H, Darby IB. 2016; The association between clinical periodontal parameters and free haem concentration within the gingival crevicular fluid: a pilot study. J Periodontal Res. 51:86–94. DOI: 10.1111/jre.12286. PMID: 26094689.17. Loesche WJ. 1976; Chemotherapy of dental plaque infections. Oral Sci Rev. 9:65–107. PMID: 1067529.18. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL Jr. 1998; Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 25:134–44. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.1998.tb02419.x. PMID: 9495612.19. Olczak T, Simpson W, Liu X, Genco CA. 2005; Iron and heme utilization in Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 29:119–44. DOI: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.001. PMID: 15652979.20. Lee SH, Baek DH. 2014; Effects of Streptococcus thermophilus on volatile sulfur compounds produced by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Arch Oral Biol. 59:1205–10. DOI: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.07.006. PMID: 25105253.21. Lee SH, Baek DH. 2013; Characteristics of Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide in co-culture with Fusobacterium nucleatum. Mol Oral Microbiol. 28:230–8. DOI: 10.1111/omi.12020. PMID: 23347381.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Characterization of hemin-binding of oral streptococci

- Characterization of the hemin-binding property of Porphyromonas endodontalis

- Characterization of Congo red binding in Streptococcus gordonii

- Effect of ascorbic acid and hemin on experimental colon carcinogenesis in mice

- Isolation and Partial Characterization of a 50 kDa Hemin-regulated Cell Envelope Protein from Prevotella nigrescens