J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Dec;36(47):e325. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e325.

How COVID-19 Affected Healthcare Workers in the Hospital Locked Down due to Early COVID-19 Cases in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Psychiatry, Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 2Division of Psychiatry, Health Screening and Promotion Center, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2523242

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e325

Abstract

- Background

The healthcare workers (HCWs) were exposed to never-experienced psychological distress during the early stage of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The aim of this study was to investigate how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the mental health of HCWs during the hospital lockdown period due to mass healthcare-associated infection during the early spread of COVID-19.

Methods

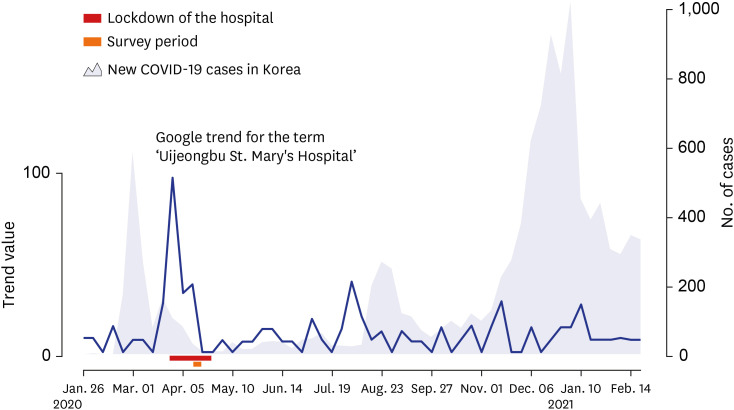

A real-time online survey was conducted between April 14–18, 2020 among HCWs who worked at the university hospital where COVID-19 was confirmed in a patient, and the hospital was shut down for 3 weeks. Along with demographic variables and work-related information, psychological distress was measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey scale, and the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-9.

Results

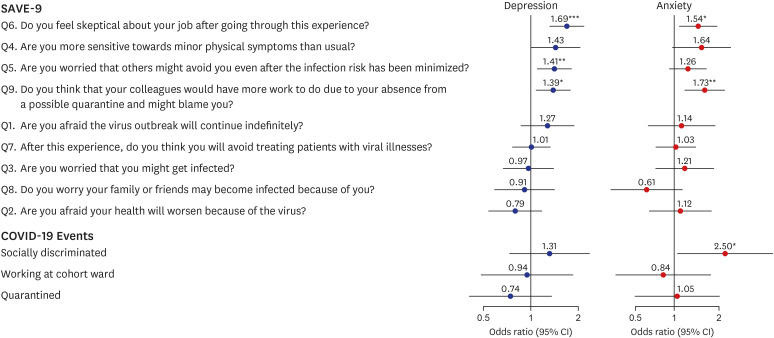

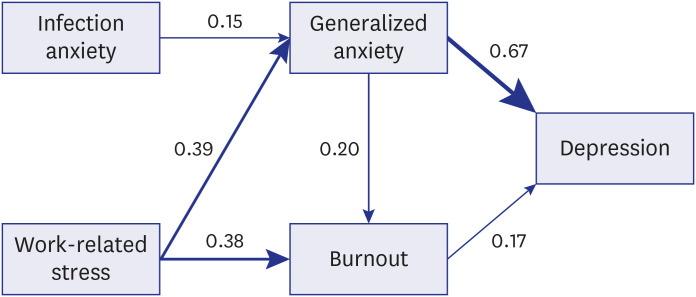

The HCWs working in the cohort ward and those who have experienced social discrimination had significantly higher level of depression (PHQ-9 score; 5.24 ± 4.48 vs. 4.15 ± 4.38; P < 0.01 and 5.89 ± 4.78 vs. 3.25 ± 3.77; P < 0.001, respectively) and anxiety (GAD-7 score; 3.69 ± 3.68 vs. 2.87 ± 3.73;P < 0.05 and 4.20 ± 4.22 vs. 2.17 ± 3.06; P < 0.001, respectively) compared to other HCWs. Worries regarding the peer relationship and the skepticism about job were associated with depression (odds ratio [OR], 1.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07–1.79; P < 0.05 and OR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.31–2.17; P < 0.001, respectively) and anxiety (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.21–2.49; P < 0.01 and OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.09–2.17; P < 0.05, respectively), while fear of infection or worsening of health was not. Path analysis showed that work-related stress associated with the viral epidemic rather than anxiety about the viral epidemic mainly contributed to depression.

Conclusion

The present observational study indicates that mental health problems of HCWs exposed to COVID-19 are associated with distress in work and social relationship. Early intervention programs focusing on these factors are necessary.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020; 579(7798):270–273. PMID: 32015507.

Article2. Kim T, Lee JY. Letter to the Editor: Risk communication, shared responsibility, and mutual trust are matters: real lessons from closure of Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital due to coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(16):e159. PMID: 32329262.

Article3. Korean Society of Infectious Diseases. Korean Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Korean Society of Epidemiology. Korean Society for Antimicrobial Therapy. Korean Society for Healthcare-associated Infection Control and Prevention. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report on the epidemiological features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in the Republic of Korea from January 19 to March 2, 2020. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(10):e112. PMID: 32174069.4. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(3):e203976. PMID: 32202646.

Article5. Zhu Z, Xu S, Wang H, Liu Z, Wu J, Li G, et al. COVID-19 in Wuhan: sociodemographic characteristics and hospital support measures associated with the immediate psychological impact on healthcare workers. EClinicalMedicine. 2020; 24:100443. PMID: 32766545.

Article6. Mertens G, Gerritsen L, Duijndam S, Salemink E, Engelhard IM. Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19): predictors in an online study conducted in March 2020. J Anxiety Disord. 2020; 74:102258. PMID: 32569905.

Article7. Taylor S, Landry CA, Rachor GS, Paluszek MM, Asmundson GJ. Fear and avoidance of healthcare workers: an important, under-recognized form of stigmatization during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Anxiety Disord. 2020; 75:102289. PMID: 32853884.

Article8. Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G, Ferrari F, Mazzetti M, Taranto P, et al. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review of the evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020; 22(8):43. PMID: 32651717.

Article9. Alnazly E, Khraisat OM, Al-Bashaireh AM, Bryant CL. Anxiety, depression, stress, fear and social support during COVID-19 pandemic among Jordanian healthcare workers. PLoS One. 2021; 16(3):e0247679. PMID: 33711026.

Article10. Hossain MM, Sultana A, Purohit N. Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: a systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. Epidemiol Health. 2020; 42:e2020038. PMID: 32512661.

Article11. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020; 395(10227):912–920. PMID: 32112714.

Article12. Giardino DL, Huck-Iriart C, Riddick M, Garay A. The endless quarantine: the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on healthcare workers after three months of mandatory social isolation in Argentina. Sleep Med. 2020; 76:16–25. PMID: 33059247.

Article13. Rehman U, Shahnawaz MG, Khan NH, Kharshiing KD, Khursheed M, Gupta K, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress among Indians in times of COVID-19 lockdown. Community Ment Health J. 2021; 57(1):42–48. PMID: 32577997.

Article14. Youssef N, Mostafa A, Ezzat R, Yosef M, El Kassas M. Mental health status of health-care professionals working in quarantine and non-quarantine Egyptian hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. East Mediterr Health J. 2020; 26(10):1155–1164. PMID: 33103742.

Article15. Koh D, Lim MK, Chia SE, Ko SM, Qian F, Ng V, et al. Risk perception and impact of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) on work and personal lives of healthcare workers in Singapore: What can we learn? Med Care. 2005; 43(7):676–682. PMID: 15970782.16. Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, Yang J, Wang Y, Li R, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87:11–17. PMID: 32240764.

Article17. Pappa O, Kefala AM, Tryfinopoulou K, Dimitriou M, Kostoulas K, Dioli C, et al. Molecular epidemiology of multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from hospitalized patients in Greece. Microorganisms. 2020; 8(11):1652.18. Daly M, Robinson E. Anxiety reported by US adults in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: population-based evidence from two nationally representative samples. J Affect Disord. 2021; 286:296–300. PMID: 33756307.

Article19. The Korea Herald. Major hospitals in Seoul area on alert against COVID-19 infiltration. Updated 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020. http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200401000837 .20. Chung S, Kim HJ, Ahn MH, Yeo S, Lee J, Kim K, Kang S, Suh S, Shin YW. Development of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) scale for assessing work-related stress and anxiety in healthcare workers in response to viral epidemics. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(47):e319.

Article21. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999; 282(18):1737–1744. PMID: 10568646.22. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing;2013.23. Choi HS, Choi JH, Park KH, Joo KJ, Ga H, Ko HJ, et al. Standardization of the Korean version of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 as a screening instrument for major depressive disorder. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2007; 28(2):114–119.24. Han C, Jo SA, Kwak JH, Pae CU, Steffens D, Jo I, et al. Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Korean version in the elderly population: the Ansan Geriatric study. Compr Psychiatry. 2008; 49(2):218–223. PMID: 18243897.

Article25. Park SJ, Choi HR, Choi JH, Kim KW, Hong JP. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Anxiety Mood. 2010; 6(2):119–124.26. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166(10):1092–1097. PMID: 16717171.27. Seo JG, Park SP. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and GAD-2 in patients with migraine. J Headache Pain. 2015; 16(1):97. PMID: 26596588.

Article28. Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press;1996.29. Shin K. The Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS): an application in South Korea. Korean J Ind Organ Psychol. 2003; 16(3):1–17.30. Matsuo T, Kobayashi D, Taki F, Sakamoto F, Uehara Y, Mori N, et al. Prevalence of health care worker burnout during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Japan. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(8):e2017271. PMID: 32749466.

Article31. Kramer V, Papazova I, Thoma A, Kunz M, Falkai P, Schneider-Axmann T, et al. Subjective burden and perspectives of German healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021; 271(2):271–281. PMID: 32815019.

Article32. Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Rourke S, Hunter JJ, Goldbloom D, Balderson K, et al. Factors associated with the psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on nurses and other hospital workers in Toronto. Psychosom Med. 2004; 66(6):938–942. PMID: 15564361.

Article33. Chong MY, Wang WC, Hsieh WC, Lee CY, Chiu NM, Yeh WC, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2004; 185(2):127–133. PMID: 15286063.

Article34. Chua SE, Cheung V, Cheung C, McAlonan GM, Wong JW, Cheung EP, et al. Psychological effects of the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong on high-risk health care workers. Can J Psychiatry. 2004; 49(6):391–393. PMID: 15283534.

Article35. Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, Al-Enazy H, Bolaji Y, Hanjrah S, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ. 2004; 170(5):793–798. PMID: 14993174.

Article36. Park JS, Lee EH, Park NR, Choi YH. Mental health of nurses working at a government-designated hospital during a MERS-CoV Outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018; 32(1):2–6. PMID: 29413067.

Article37. Ramaci T, Barattucci M, Ledda C, Rapisarda V. Social stigma during COVID-19 and its impact on HCWs outcomes. Sustainability. 2020; 12(9):3834.

Article38. Wong TW, Yau JK, Chan CL, Kwong RS, Ho SM, Lau CC, et al. The psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on healthcare workers in emergency departments and how they cope. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005; 12(1):13–18. PMID: 15674079.

Article39. Mitchell A, Cummins T, Spearing N, Adams J, Gilroy L. Nurses' experience with vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). J Clin Nurs. 2002; 11(1):126–133. PMID: 11845749.

Article40. Maunder RG, Leszcz M, Savage D, Adam MA, Peladeau N, Romano D, et al. Applying the lessons of SARS to pandemic influenza: an evidence-based approach to mitigating the stress experienced by healthcare workers. Can J Public Health. 2008; 99(6):486–488. PMID: 19149392.41. Naser AY, Al-Hadithi HT, Dahmash EZ, Alwafi H, Alwan SS, Abdullah ZA. The effect of the 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak on social relationships: a cross-sectional study in Jordan. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020; 20764020966631. PMID: 33103566.

Article42. Trougakos JP, Chawla N, McCarthy JM. Working in a pandemic: exploring the impact of COVID-19 health anxiety on work, family, and health outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2020; 105(11):1234–1245. PMID: 32969707.

Article43. Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 288:112936. PMID: 32276196.

Article44. Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, Fan B, Fang Y, Kong J, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry. 2012; 53(1):15–23. PMID: 21489421.

Article45. Su TP, Lien TC, Yang CY, Su YL, Wang JH, Tsai SL, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and psychological adaptation of the nurses in a structured SARS caring unit during outbreak: a prospective and periodic assessment study in Taiwan. J Psychiatr Res. 2007; 41(1-2):119–130. PMID: 16460760.

Article46. Wong WC, Wong SY, Lee A, Goggins WB. How to provide an effective primary health care in fighting against severe acute respiratory syndrome: the experiences of two cities. Am J Infect Control. 2007; 35(1):50–55. PMID: 17276791.

Article47. Poon E, Liu KS, Cheong DL, Lee CK, Yam LY, Tang WN. Impact of severe respiratory syndrome on anxiety levels of front-line health care workers. Hong Kong Med J. 2004; 10(5):325–330. PMID: 15479961.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Factors Affecting Fear of COVID-19 Infection in Healthcare Workers in COVID-19 Dedicated Teams: Focus on Professional Quality of Life

- Burnout among Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic

- Assessment and Management of Dysphagia during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Hospital Infection Control Practice in the COVID-19 Era: An Experience of University Affiliated Hospital

- Insights and pearls of healthcare systems management of COVID-19 in Asia and its relevance to Asian transplant services