Korean J Women Health Nurs.

2021 Sep;27(3):196-208. 10.4069/kjwhn.2021.09.08.

Does a nurse-led postpartum self-care program for first-time mothers in Bangladesh improve postpartum fatigue, depressive mood, and maternal functioning?: a non-synchronized quasi-experimental study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Faculty, National Institute of Advanced Nursing Education and Research, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 2College of Nursing, Mo-Im Kim Nursing Research Institute, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

- 3College of Nursing, Ajou University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2521515

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2021.09.08

Abstract

- Purpose

This study aimed to test the efficacy of a nurse-led postpartum self-care (NL-PPSC) intervention at reducing postpartum fatigue (PPF) and depressive mood and promoting maternal functioning among first-time mothers in Bangladesh.

Methods

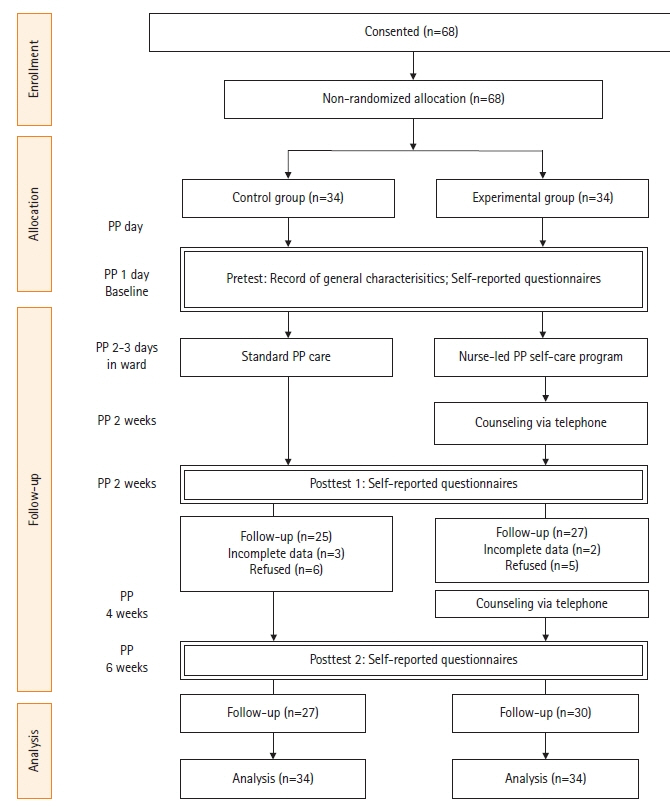

A non-synchronized quasi-experimental design was used. First-time mothers were recruited during postpartum (PP) and assigned to the experimental or control group (34 each). The experimental group attended the NL-PPSC—a 1-day intervention that focused on increasing self-efficacy—at a hospital in person. The control group received usual care. Data on PPF, depressive mood, maternal functioning, self-care behaviors, PP self-efficacy, and self-care knowledge were collected at 2 weeks PP (attrition 23.5%) and 6 weeks PP (attrition 16.1%). Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, bivariate statistics, and linear mixed model analysis.

Results

One-third (33.3%) of new mothers experienced depressive mood (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores of ≥13 points). The NL-PPSC intervention statistically significantly decreased PPF (β=–6.17, SE=1.81, t=–3.39, p<.01) and increased maternal functioning at 6 weeks PP in the experimental group (β=13.72, t=3.73, p<.01) as opposed to the control group. Knowledge was also statistically significant for increased maternal functioning over time (β=.37, SE=.18, t=2.03, p<.05). However, no statistically significant differences in PP depressive mood were observed over time.

Conclusion

The NL-PPSC intervention was feasible and effective at improving fatigue and maternal functioning in Bangladeshi mothers at 6 weeks PP. PP care knowledge was effective at improving maternal functioning; this finding supports the implementation of the NL-PPSC intervention for new mothers after childbirth.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Kim Y, Dee V. Self-care for health in rural Hispanic women at risk for postpartum depression. Matern Child Health J. 2017; 21(1):77–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2096-8.

Article2. Dunning M, Seymour M, Cooklin A, Giallo R. Wide awake parenting: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial of a parenting program for the management of post-partum fatigue. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-26.

Article3. Giallo R, Cooklin A, Dunning M, Seymour M. The efficacy of an intervention for the management of postpartum fatigue. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014; 43(5):598–613. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12489.

Article4. Shafaie FS, Mirghafourvand M, Bagherinia M. The association between maternal self-confidence and functional status in primiparous women during postpartum period, 2015-2016. Int J Women’s Health Reprod Sci. 2017; 5(3):200–204. https://doi.org/10.15296/ijwhr.2017.36.

Article5. Barbosa EM, Sousa AA, Vasconcelos MG, Carvalho RE, Oria MO, Rodrigues DP. Educational technologies to encourage (self) care in postpartum women. Rev Bras Enferm. 2016; 69(3):545–553. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167.2016690323i.

Article6. Schaar GL, Hall M. A nurse-led initiative to improve obstetricians’ screening for postpartum depression. Nurs Womens Health. 2013; 17(4):306–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-486X.12049.

Article7. Bagherinia M, Mirghafourvand M, Shafaie FS. The effect of educational package on functional status and maternal self-confidence of primiparous women in postpartum period: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017; 30(20):2469–2475. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2016.1253061.

Article8. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, and ICF International. Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2014. Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Rockville (MD): NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International;2016.9. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Health and morbidity status survey-2012 [Internet]. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning: 2013 [cited 2021 Sep 14]. Available from: http://bbs.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bbs.portal.gov.bd/page/4c7eb0f0_e780_4686_b546_b4fa0a8889a5/HMSS.pdf.10. Kamiya Y, Yoshimura Y, Islam MT. An impact evaluation of the safe motherhood promotion project in Bangladesh: evidence from Japanese aid-funded technical cooperation. Soc Sci Med. 2013; 83:34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.035.

Article11. Barnes J, Stuart J, Allen E, Petrou S, Sturgess J, Barlow J, et al. Randomized controlled trial and economic evaluation of nurse-led group support for young mothers during pregnancy and the first year postpartum versus usual care. Trials. 2017; 18(1):508. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2259-y.

Article12. Jolly SP, Rahman M, Afsana K, Yunus FM, Chowdhury AM. Evaluation of maternal health service indicators in urban slum of Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2016; 11(10):e0162825. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162825.

Article13. Birdsall KA. Quiet revolution: strengthening the routine health information system in Bangladesh. Eschborn, Germany: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ);2014.14. Mobile Alliance for Maternal Action (MAMA) Bangladesh. MAMA “Aponjon” formative research report [Internet]. Dnet, and Johns Hopkins University Global mHealth Initiative; 2013 [cited 2016 Dec 6]. Available from: Available from: http://www.mobilemamaalliance.org/sites/default/files/MAMA%20Bangladesh%20Formative%20Research%20Report.pdf.15. Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N; TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004; 94(3):361–366. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.94.3.361.

Article16. Bandura A. Social foundations of thought & action: a social cognitive theory. England Cliffs (NJ): Prentice-Hall, Inc;1986.17. Jeon M, Hwang Y. Effects of an educational program on pre-and postpartum self-care knowledge, efficacy of self-care, and interest in health of marriage immigrant women in South Korea. J Converg Inf Technol. 2013; 8(14):508–514.18. Leahy-Warren P, McCarthy G. Maternal parental self-efficacy in the postpartum period. Midwifery. 2011; 27(6):802–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2010.07.008.

Article19. Milligan RA, Parks PL, Kitzman H, Lenz ER. Measuring women’s fatigue during the postpartum period. J Nurs Meas. 1997; 5(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.5.1.3.

Article20. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987; 150:782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782.

Article21. Williams A, Sarker M, Ferdous ST. Cultural attitudes toward postpartum depression in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Med Anthropol. 2018; 37(3):194–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2017.1318875.

Article22. Khatun F, Lee TW, Rani E, Biswas G, Raha P, Kim S. The relationship among fatigue, depressive mood, self-care agency, and self-care action of first-time mothers in Bangladesh. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2018; 24(1):49–57. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2018.24.1.49.

Article23. Barkin JL, Wisner KL. The role of maternal self-care in new motherhood. Midwifery. 2013; 29(9):1050–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.10.001.

Article24. Denyes MJ. Denyes self-care instrument. Detroit (MI): College of Nursing, Wayne state University;1990.25. Shin HS, Kim SH, Kwon SH. Effects of education on primiparas’ postpartal care. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2000; 6(1):34–45.26. Park MK. Effects of postpartum care program for primiparous women and care-givers on the knowledge and behavior of postpartum care and postpartum recovery in primiparous women [doctoral dissertation]. Gwangju: Chonnam University;2003.27. Molenda M. In search of the elusive ADDIE model. Perf Improv. 2003; 42:34–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.4930420508.

Article28. Bandura A. Self-efficacy. In : Ramachandran VS, editor. Encyclopedia of human behavior, Vol. 4. New York: Academic Press;1994. p. 71–81.29. Ho SM, Heh SS, Jevitt CM, Huang LH, Fu YY, Wang LL. Effectiveness of a discharge education program in reducing the severity of postpartum depression: a randomized controlled evaluation study. Patient Educ Couns. 2009; 77(1):68–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.01.009.

Article30. Phipps MG, Raker CA, Ware CF, Zlotnick C. Randomized controlled trial to prevent postpartum depression in adolescent mothers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 208(3):192. e1-192.e1926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.12.036.

Article31. Gausia K, Fisher C, Algin S, Oosthuizen J. Validation of the Bangla version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for a Bangladeshi sample. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2007; 25(4):308–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830701644896.

Article32. Oleiwi SS, Ali RM. Effectiveness of instruction-oriented intervention for primipara women upon episiotomy and self-perineal care at ibn Al-Baladi Hospital. Iraqi National J Nurs Sci. 2010; 23(2):8–17.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Relationships among Postpartum Fatigue, Depressive Mood, Self-care Agency, and Self-care Action of First-time Mothers in Bangladesh

- Development and Validation of a Postpartum Care Mobile Application for First-time Mothers

- Effects of a Maternal Role Adjustment Program on First-time Mothers

- Effects of a Postpartum Care Program for Postpartum Women on Postpartum Activity and Postpartum Discomfort in Primiparous Women

- Effects of Postpartum Massage Program on Stress response in the Cesarean section Mothers