J Korean Foot Ankle Soc.

2021 Sep;25(3):126-132. 10.14193/jkfas.2021.25.3.126.

Correlation between Internet Search Query Data and the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service Data for Seasonality of Plantar Fasciitis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Seoul Red Cross Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2520103

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14193/jkfas.2021.25.3.126

Abstract

- Purpose

This study examined whether there are seasonal variations in the number of plantar fasciitis cases from the database of the Korean Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service and an internet search of the volume data related to plantar fasciitis and whether there are correlations between variations.

Materials and Methods

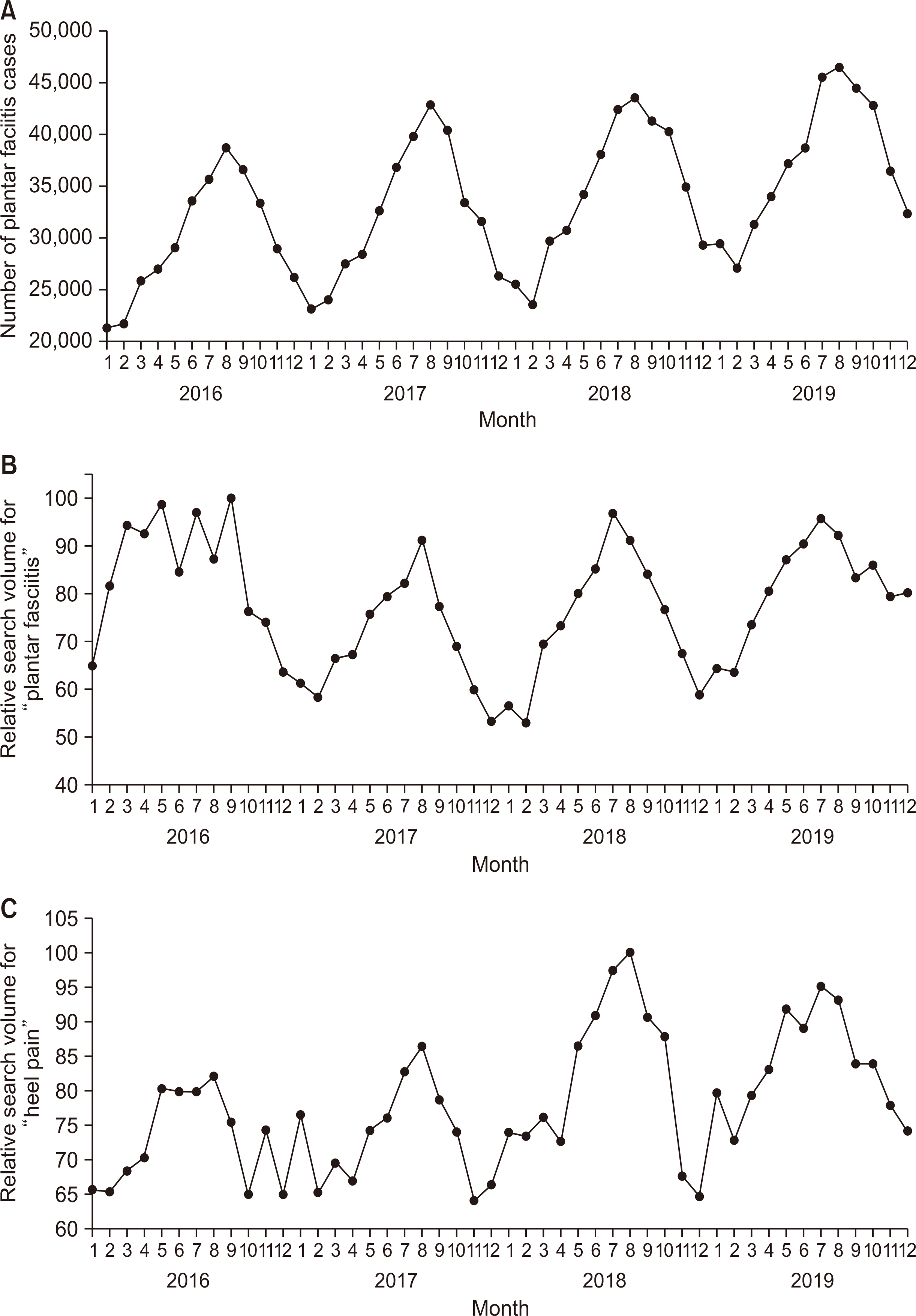

The number of plantar fasciitis cases per month was acquired from the Korean Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service from January 2016 to December 2019. The monthly internet relative search volumes for the keywords ‘‘plantar fasciitis” and ‘‘heel pain” were collected during the same period from DataLab, an internet search query trend service provided by the Korean portal website, Naver. Cosinor analysis was performed to confirm the seasonality of the monthly number of cases and relative search volumes, and Pearson and Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to assess the correlation between them.

Results

The number of cases with plantar fasciitis and the relative search volume for the keywords “plantar fasciitis” and “heel pain” all showed significant seasonality (p<0.001), with the highest in the summer and the lowest in the winter. The number of cases with plantar fasciitis was correlated significantly with the relative search volumes of the keywords “plantar fasciitis” (r=0.632; p<0.001) and “heel pain” (r=0.791; p<0.001), respectively.

Conclusion

Both the number of cases with plantar fasciitis and the internet search data for related keywords showed seasonality, which was the highest in summer. The number of cases showed a significant correlation with the internet search data for the seasonality of plantar fasciitis. Internet big data could be a complementary resource for researching and monitoring plantar fasciitis.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Neufeld SK, Cerrato R. 2008; Plantar fasciitis: evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 16:338–46. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200806000-00006. DOI: 10.5435/00124635-200806000-00006. PMID: 18524985.

Article2. Crawford F, Thomson C. 2003; Interventions for treating plantar heel pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):CD000416. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000416. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000416.

Article3. Riddle DL, Schappert SM. 2004; Volume of ambulatory care visits and patterns of care for patients diagnosed with plantar fasciitis: a national study of medical doctors. Foot Ankle Int. 25:303–10. doi: 10.1177/107110070402500505. DOI: 10.1177/107110070402500505. PMID: 15134610.

Article4. Rasenberg N, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Bindels PJ, van Middelkoop M. , van der Lei J. 2019; Incidence, prevalence, and management of plantar heel pain: a retrospective cohort study in Dutch primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 69:e801–8. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X706061. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp19X706061. PMID: 31636128. PMCID: PMC6805165.

Article5. Cervellin G, Comelli I, Lippi G. 2017; Is Google Trends a reliable tool for digital epidemiology? Insights from different clinical settings. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 7:185–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.06.001. DOI: 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.06.001. PMID: 28756828. PMCID: PMC7320449.

Article6. Nuti SV, Wayda B, Ranasinghe I, Wang S, Dreyer RP, Chen SI, et al. 2014; The use of google trends in health care research: a systematic review. PLoS One. 9:e109583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109583. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109583. PMID: 25337815. PMCID: PMC4215636.

Article7. Arora VS, McKee M, Stuckler D. 2019; Google trends: opportunities and limitations in health and health policy research. Health Policy. 123:338–41. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.01.001. DOI: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.01.001. PMID: 30660346.

Article8. Carr LJ, Dunsiger SI. 2012; Search query data to monitor interest in behavior change: application for public health. PLoS One. 7:e48158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048158. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048158. PMID: 23110198. PMCID: PMC3479111.

Article9. Xu C, Yang H, Sun L, Cao X, Hou Y, Cai Q, et al. 2020; Detecting lung cancer trends by leveraging real-world and internet-based data: infodemiology study. J Med Internet Res. 22:e16184. doi: 10.2196/16184. DOI: 10.2196/16184. PMID: 32163035. PMCID: PMC7099398.

Article10. Chen Y, Zhang Y, Xu Z, Wang X, Lu J, Hu W. 2019; Avian Influenza A (H7N9) and related Internet search query data in China. Sci Rep. 9:10434. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46898-y. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-46898-y. PMID: 31320681. PMCID: PMC6639335.

Article11. Bahk GJ, Kim YS, Park MS. 2015; Use of internet search queries to enhance surveillance of foodborne illness. Emerg Infect Dis. 21:1906–12. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.141834. DOI: 10.3201/eid2111.141834. PMID: 26485066. PMCID: PMC4622232.

Article12. Cho S, Sohn CH, Jo MW, Shin SY, Lee JH, Ryoo SM, et al. 2013; Correlation between national influenza surveillance data and google trends in South Korea. PLoS One. 8:e81422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081422. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081422. PMID: 24339927. PMCID: PMC3855287.

Article13. Woo H, Cho Y, Shim E, Lee JK, Lee CG, Kim SH. 2016; Estimating influenza outbreaks using both search engine query data and social media data in South Korea. J Med Internet Res. 18:e177. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4955. DOI: 10.2196/jmir.4955. PMID: 27377323. PMCID: PMC4949385.

Article14. Shin SY, Seo DW, An J, Kwak H, Kim SH, Gwack J, et al. 2016; High correlation of Middle East respiratory syndrome spread with Google search and Twitter trends in Korea. Sci Rep. 6:32920. doi: 10.1038/srep32920. DOI: 10.1038/srep32920. PMID: 27595921. PMCID: PMC5011762.

Article15. BizSpring Inc. Internet trend [Internet]. BizSpring Inc;Seoul: Available from: http://www.internettrend.co.kr/trendForward.tsp. cited 2021 Jan 16.16. Tucker P, Gilliland J. 2007; The effect of season and weather on physical activity: a systematic review. Public Health. 121:909–22. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.04.009. DOI: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.04.009. PMID: 17920646.

Article17. Breyer BN, Sen S, Aaronson DS, Stoller ML, Erickson BA, Eisenberg ML. 2011; Use of Google Insights for Search to track seasonal and geographic kidney stone incidence in the United States. Urology. 78:267–71. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.01.010. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.01.010. PMID: 21459414. PMCID: PMC4551459.

Article18. Senecal C, Widmer RJ, Lerman LO, Lerman A. 2018; Association of search engine queries for chest pain with coronary heart disease epidemiology. JAMA Cardiol. 3:1218–21. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3459. DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3459. PMID: 30422176. PMCID: PMC6583097.

Article19. International Telecommunication Union. Measuring the information society report 2018 [Internet]. International Telecommunication Union;Geneva: Available from: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/misr2018.aspx. cited 2021 Feb 19.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Analysis of interest in implant using a big data: A web-based study

- A guide for the utilization of Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service National Patient Samples

- Introducing big data analysis using data from National Health Insurance Service

- Pediatric Cancer Research using Healthcare Big Data

- Towards Actualizing the Value Potential of Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) Data as a Resource for Health Research: Strengths, Limitations, Applications, and Strategies for Optimal Use of HIRA Data