J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Jul;36(27):e185. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e185.

Development of a Short Form Depression Screening Questionnaire for Korean Soldiers

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Psychiatry, Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon, Korea

- 2Department of Prevention Medicine, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Seoul Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Psychiatry, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea

- KMID: 2518351

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e185

Abstract

- Background

The frequencies of South Korean soldiers' depression and resulting suicide are increasing every year. Thus, this study aimed to develop and confirm the reliability and validity of a simple short form depression screening scale for soldiers.

Methods

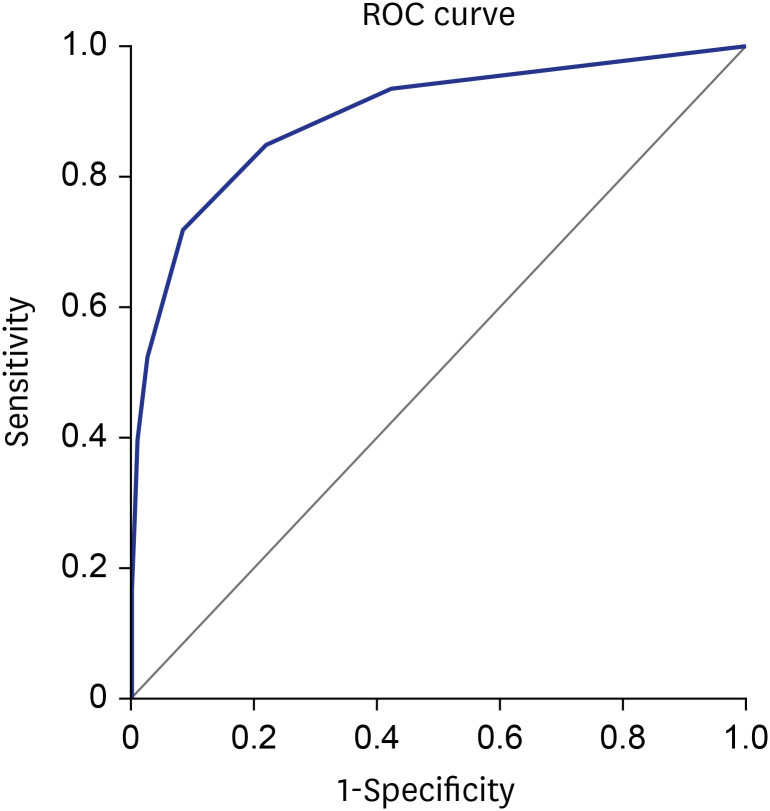

This study was conducted as part of a 2013 research project named ‘The Epidemiological Study on the Prevalence of Depression in Military Service and a Search for High Risk Group Management.’ Clinical depression was diagnosed using the Korean version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview and suicide risk was assessed through the Korean version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Furthermore, the Center for Epidemiological Studies for Depression Scale (CES-D), the Stress Response Inventory, and the Barret Impulsiveness Scale were employed. Of the 20 CES-D items, three of the most correlated items with clinical diagnosis were derived to form the short form scale. Analyses for internal consistency, concurrent validity, and factor analysis were implemented for its validation. We performed a receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis using a clinical diagnosis of depression as a gold standard to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) value, cut-off score, and corresponding sensitivity and specificity to that cut-off score.

Results

According to the results of the correlation analysis, 7, 18, and 4 were selected to be on our scale. The three-item scale was reliable with a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.720, and a factor was derived from the factor analysis. The ROC analysis showed a high discriminant validity, with an AUC value of 0.891. The sensitivity and specificity were 84.8% and 78.2%, and 71.7% and 91.6%, respectively, for each when the selected cut-off scores were 2 and 3, respectively. Depression screened through the scale when the cut-off score was 2 or 3 was significantly associated with suicidality, stress, and social support.

Conclusion

The depression screening questionnaire for Korean soldiers developed through this study demonstrated high reliability and validity. Since it comprises only three items, it can be utilized easily and frequently. It is expected to be employed in a large-scale suicide prevention project targeting military soldiers in the future; it will be beneficial in selecting high-risk groups for depression.

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Association of Depression With Susceptibility and Adaptation to Seasickness in the Military Seafarers

Chan-Young Park, Sungjin Park, Seok-Gil Han, Taehui Sung, Do Yeon Kim

J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37(29):e231. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e231.

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2017.2. Cho MJ, Seong SJ, Park JE, Chung IW, Lee YM, Bae A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV mental disorders in South Korean adults: the Korean Epidemiologic Catchment Area study 2011. Psychiatry Investig. 2015; 12(2):164–170.

Article3. Orsolini L, Latini R, Pompili M, Serafini G, Volpe U, Vellante F, et al. Understanding the complex of suicide in depression: from research to clinics. Psychiatry Investig. 2020; 17(3):207–221.

Article4. Jeon HJ. Epidemiologic studies on depression and suicide. J Korean Med Assoc. 2012; 55(4):322–328.

Article5. Beck A, Crain AL, Solberg LI, Unützer J, Glasgow RE, Maciosek MV, et al. Severity of depression and magnitude of productivity loss. Ann Fam Med. 2011; 9(4):305–311. PMID: 21747101.

Article6. Hong JP, Lee DW, Sim YJ, Kim YH. Awareness, attitude and impact of perceived depression in the workplace in Korea. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2015; 54(2):188–201.

Article7. Coretti S, Rumi F, Cicchetti A. The social cost of major depression: a systematic review. J Rev Eur Stud. 2019; 11(1):73.

Article8. Chang SM, Hong JP, Cho MJ. Economic burden of depression in South Korea. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012; 47(5):683–689. PMID: 21526429.

Article9. Ministry of National Defense Republic of Korea. 2012 Defense White Paper. Seoul, Korea: Defense Policy Division, Policy Planning Bureau;2012.10. Lim KS. Factor analysis related to soldier's suicide prevention program needs. J Mil Nurs Res. 2008; 26(2):162–177.11. Cho MJ, Chang SM, Lee YM, Bae A, Ahn JH, Son J, et al. Prevalence of DSM-IV major mental disorders among Korean adults: a 2006 National Epidemiologic Survey (KECA-R). Asian J Psychiatr. 2010; 3(1):26–30. PMID: 23051134.

Article12. Ham BJ, Jeon HJ, Jang SM, Lee HW, Lee HJ, Shim EJ. Ministry of Defense Research Service Project Report-Investigation of the Prevalence of Mental Disorders (Including Acute Stress Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) in the Military. Seoul, Korea: Seoul National University College of Medicine;2007.13. Sorenson SB, Rutter CM, Aneshensel CS. Depression in the community: an investigation into age of onset. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991; 59(4):541–546. PMID: 1918558.

Article14. Cho MJ, Chang SM, Hahm BJ, Chung IW, Bae A, Lee YM, et al. Lifetime risk and age of onset distributions of psychiatric disorders: analysis of national sample survey in South Korea. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012; 47(5):671–681. PMID: 21528435.

Article15. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977; 1(3):385–401.16. Zhang W, O'Brien N, Forrest JI, Salters KA, Patterson TL, Montaner JS, et al. Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One. 2012; 7(7):e40793. PMID: 22829885.

Article17. Cole JC, Rabin AS, Smith TL, Kaufman AS. Development and validation of a Rasch-derived CES-D short form. Psychol Assess. 2004; 16(4):360–372. PMID: 15584795.

Article18. Moullec G, Maïano C, Morin AJ, Monthuy-Blanc J, Rosello L, Ninot G. A very short visual analog form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) for the idiographic measurement of depression. J Affect Disord. 2011; 128(3):220–234. PMID: 20609480.

Article19. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998; 59(Suppl 20):22–33.20. Yoo SW, Kim YS, Noh JS, Oh KS, Kim CH, NamKoong K, et al. Validity of Korean version of the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview. Anxiety Mood. 2006; 2(1):50–55.21. Cho MJ, Kim KH. Use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale in Korea. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998; 186(5):304–310. PMID: 9612448.

Article22. Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO--Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994; 28(1):57–84. PMID: 8064641.

Article23. Cho MJ, Hahm BJ, Suh DW, Hong JP, Bae JN, Kim JK, et al. Development of a Korean version of the composite international diagnostic interview (K-CIDI). J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2002; 41(1):123–137.24. Koh KB, Park JK, Kim CH. Development of the stress response inventory. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2000; 39(4):707–719.25. Choi SM, Kang TY, Woo JM. Development and validation of a modified form of the stress response inventory for workers. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2006; 45(6):541–553.26. Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995; 51(6):768–774. PMID: 8778124.

Article27. Lee HS. Impulsivity Test. Seoul, Korea: Korean Guidance;1992.28. Lubben J, Gironda M. Centrality of social ties to the health and well-being of older adults. In : Berkman B, Harooytan L, editors. Social Work and Health Care in an Aging World: Informing Education, Policy, Practice, and Research. New York, NY, USA: Springer;2003. p. 319–350.29. Bland JM, Altman DG. Cronbach's alpha. BMJ. 1997; 314(7080):572. PMID: 9055718.30. Metz CE. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin Nucl Med. 1978; 8(4):283–298. PMID: 112681.

Article31. Altman DG, Bland JM. Diagnostic tests 2: predictive values. BMJ. 1994; 309(6947):102. PMID: 8038641.32. Granö N, Keltikangas-Järvinen L, Kouvonen A, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, et al. Impulsivity as a predictor of newly diagnosed depression. Scand J Psychol. 2007; 48(2):173–179. PMID: 17430370.

Article33. Paykel ES. Life events, social support and depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1994; 377:50–58. PMID: 8053367.

Article34. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D.C., USA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing;2013.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Development of a Short Form Depression Screening Questionnaire for Korean Career Soldiers

- The Comparison of M-B CDI-K Short Form and K-ASQ as Screening Test for Language Development

- A Study on Comparison of Classification and Regression Tree and Multiple Regression for Predicting of Soldiers' Depression

- A Short form of the Samsung Dementia Questionnaire ( S-SDQ ): development and cross-validation

- Comparing Various Short-Form Geriatric Depression Scales in Elderly Patients