Korean Circ J.

2021 Jul;51(7):610-622. 10.4070/kcj.2021.0051.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Hypertension Screening in the Korea National Health Screening Program

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases Etiology Research Center, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Division of Cardiology, College of Medicine, Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Healthcare Management, Graduate School of Public Health, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2517490

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2021.0051

Abstract

- Background and Objectives

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of routine hypertension (HTN) screening as a part of the national health-screening program.

Methods

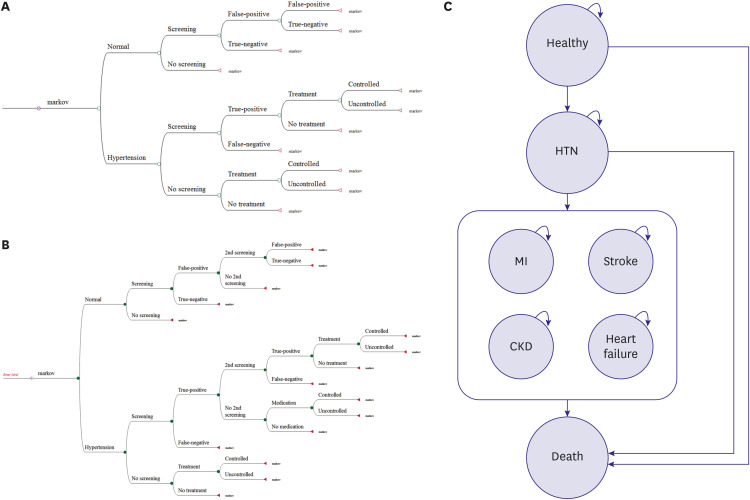

Two aspects of cost-effectiveness were examined using the national general healthscreening program. First, the cost of case-finding was computed for 5-year interval age groups. Second, the cost per quality adjusted life years (QALYs) gained were estimated for 12 different scenarios varying examination starting age, pattern and interval compared with no screening.

Results

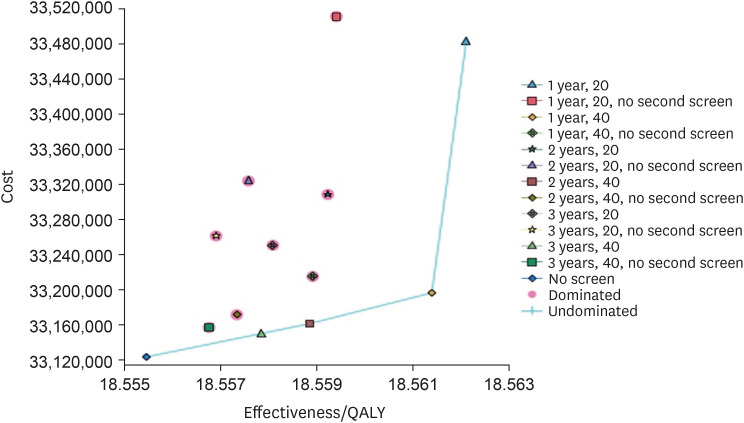

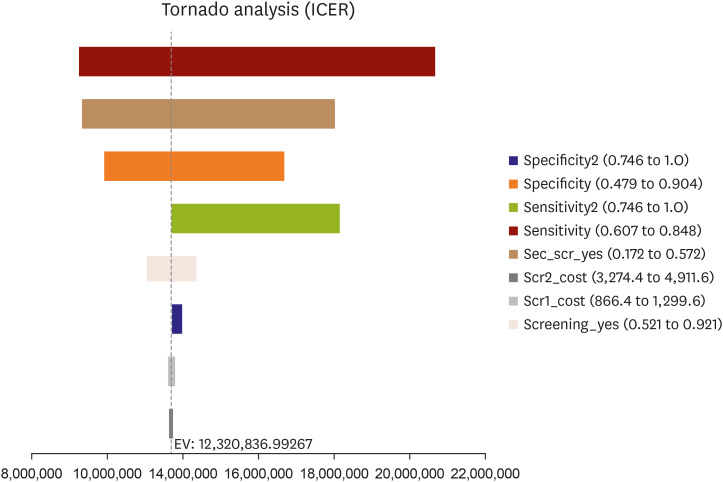

The cost of finding one new HTN case was low as 26,284 Korean won (KRW) (approximately [approx.] United States Dollar 21) for 70–79 years old to as high as 70,552 KRW for 40–44 years old. Compared with no screening, the costs per QALYs of the following screening strategies were below the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio threshold (approx. KRW 30.5 million): first screening examination with the second confirmatory examination in adults aged ≥40 years every 3 years (KRW 10.2 million), every 2 years (KRW 13.2 million), or annually (KRW 19.9 million). One-way sensitivity analyses suggest that the results were mostly influenced by the sensitivity of the first screening examination, followed by the examination rate of the second confirmatory examination.

Conclusions

HTN screening as a part of routine national health screening program was cost- effective for adults aged 40 years or older. The most cost-effective HTN screening strategy was the first screening examination with the second confirmatory examination in aged 40 years or older every 3 years.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Optimal Strategy of Hypertension Screening in a Nationwide Health Examination: Early and Periodic Blood Pressure Measurement

Eun Mi Lee

Korean Circ J. 2021;51(7):623-625. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0185.Epidemiology of PAH in Korea: An Analysis of the National Health Insurance Data, 2002–2018

Albert Youngwoo Jang, Hyeok-Hee Lee, Hokyou Lee, Hyeon Chang Kim, Wook-Jin Chung

Korean Circ J. 2023;53(5):313-327. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2022.0231.

Reference

-

1. Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990–2015. JAMA. 2017; 317:165–182. PMID: 28097354.2. Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V. Preference-based EQ-5D index scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Decis Making. 2006; 26:410–420. PMID: 16855129.

Article3. Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011; 123:933–944. PMID: 21262990.4. Kim HC, Cho SMJ, Lee H, et al. Korea hypertension fact sheet 2020: analysis of nationwide population-based data. Clin Hypertens. 2021; 27:8. PMID: 33715619.

Article5. Siu AL. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015; 163:778–786. PMID: 26458123.

Article6. Yoo JS, Choe EY, Kim YM, Kim SH, Won YJ. Predictive costs in medical care for Koreans with metabolic syndrome from 2009 to 2013 based on the National Health Insurance claims dataset. Korean J Intern Med. 2020; 35:936–945. PMID: 31422650.

Article7. Lee SW, Lee HY, Ihm SH, Park SH, Kim TH, Kim HC. Status of hypertension screening in the Korea National General Health Screening Program: a questionnaire survey on 210 screening centers in two metropolitan areas. Clin Hypertens. 2017; 23:23. PMID: 29225914.

Article8. Nguyen TP, Wright EP, Nguyen TT, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of screening for and managing identified hypertension for cardiovascular disease prevention in Vietnam. PLoS One. 2016; 11:e0155699. PMID: 27192051.

Article9. Lovibond K, Jowett S, Barton P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of options for the diagnosis of high blood pressure in primary care: a modelling study. Lancet. 2011; 378:1219–1230. PMID: 21868086.

Article10. Briggs A, Sculpher M. An introduction to Markov modelling for economic evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998; 13:397–409. PMID: 10178664.

Article11. Seong SC, Kim YY, Khang YH, et al. Data resource profile: the National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46:799–800. PMID: 27794523.12. Kang SH, Kim SH, Cho JH, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in Korea. Sci Rep. 2019; 9:10970. PMID: 31358791.

Article13. Seong SC, Kim YY, Park SK, et al. Cohort profile: the National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) in Korea. BMJ Open. 2017; 7:e016640.

Article14. Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009; 338:b1665. PMID: 19454737.

Article15. Neal B, MacMahon S, Chapman N; Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood-pressure-lowering drugs: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. Lancet. 2000; 356:1955–1964. PMID: 11130523.16. Kim L, Kim JA, Kim S. A guide for the utilization of health insurance review and assessment service national patient samples. Epidemiol Health. 2014; 36:e2014008. PMID: 25078381.

Article17. Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Tonelli M, et al. Population based screening for chronic kidney disease: cost effectiveness study. BMJ. 2010; 341:c5869. PMID: 21059726.

Article18. Feldman AM, de Lissovoy G, Bristow MR, et al. Cost effectiveness of cardiac resynchronization therapy in the comparison of medical therapy, pacing, and defibrillation in heart failure (COMPANION) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:2311–2321. PMID: 16360064.

Article19. La Puma J, Lawlor EF. Quality-adjusted life-years. Ethical implications for physicians and policymakers. JAMA. 1990; 263:2917–2921. PMID: 2110986.

Article20. König HH, Barry JC. Cost effectiveness of treatment for amblyopia: an analysis based on a probabilistic Markov model. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004; 88:606–612. PMID: 15090409.21. Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, Kamlet MS, Russell LB. Recommendations of the panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 1996; 276:1253–1258. PMID: 8849754.

Article22. Shin J, Cho MC. Updated reasons and clinical implications of new Korean hypertension guidelines for cardiologists. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:476–484. PMID: 32281319.

Article23. Jung MH, Ihm SH. Improving the quality of hypertension management: multifaceted approach. Korean Circ J. 2019; 49:528–531. PMID: 31074223.

Article24. Algabbani FM, Algabbani AM. Treatment adherence among patients with hypertension: findings from a cross-sectional study. Clin Hypertens. 2020; 26:18. PMID: 32944283.

Article25. Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Dolovich L, et al. Improving cardiovascular health at population level: 39 community cluster randomised trial of Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP). BMJ. 2011; 342:d442. PMID: 21300712.

Article26. Lin CC, Ko CY, Liu JP, Lee YL, Chie WC. Nationwide periodic health examinations promote early treatment of hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidemia in adults: experience from Taiwan. Public Health. 2011; 125:187–195. PMID: 21440274.

Article27. Deng BH, Liu HW, Pan PC, Mau LW, Chiu HC. Cost-effectiveness of elderly health examination program: the example of hypertension screening. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2007; 23:17–24. PMID: 17282981.

Article28. Wang YC, Cheung AM, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of blood pressure screening in adolescents in the United States. J Pediatr. 2011; 158:257–264.e1-7. PMID: 20850759.

Article29. Pyun WB. Hypertension control in young population: the earlier, the better. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:1092–1094. PMID: 33258317.

Article30. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43:69–77. PMID: 24585853.

Article31. National Health Insurance Service. A report on the in-depth analysis of the Korea Health Panel Survey 2013. Wonju: National Health Insurance Service;2013.32. Ministry of Employment and Labor. Survey on work status by employment type. Sejong: Ministry of Employment and Labor;2016.33. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. A report on the Korea Health Panel Survey of 2008. Sejong: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2009.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Cost analysis of hypertension screening program

- Methodological Review of Cost Effectiveness Analysis of Cancer Screening

- A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Mass Screening for Diabetes Mellitus

- Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of a Hyperlipidemia Mass Screening Program in Korea

- Cost Utility Analysis of National Cancer Screening Program for Gastric Cancer in Korea: A Markov Model Analysis