Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg.

2021 May;25(2):259-264. 10.14701/ahbps.2021.25.2.259.

Indication and surgical techniques of bypass choledochojejunostomy for intractable choledocholithiasis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Departments of Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Departments of Internal Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2516247

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14701/ahbps.2021.25.2.259

Abstract

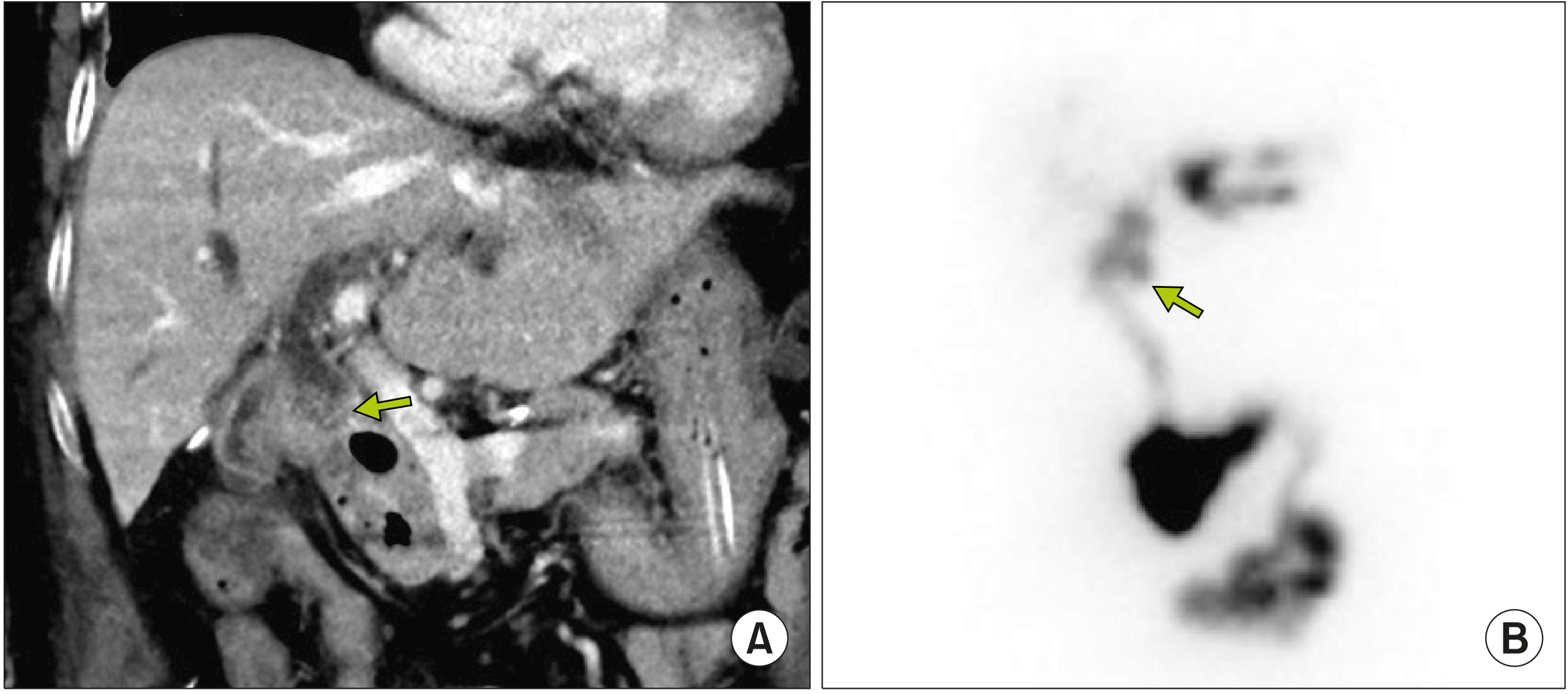

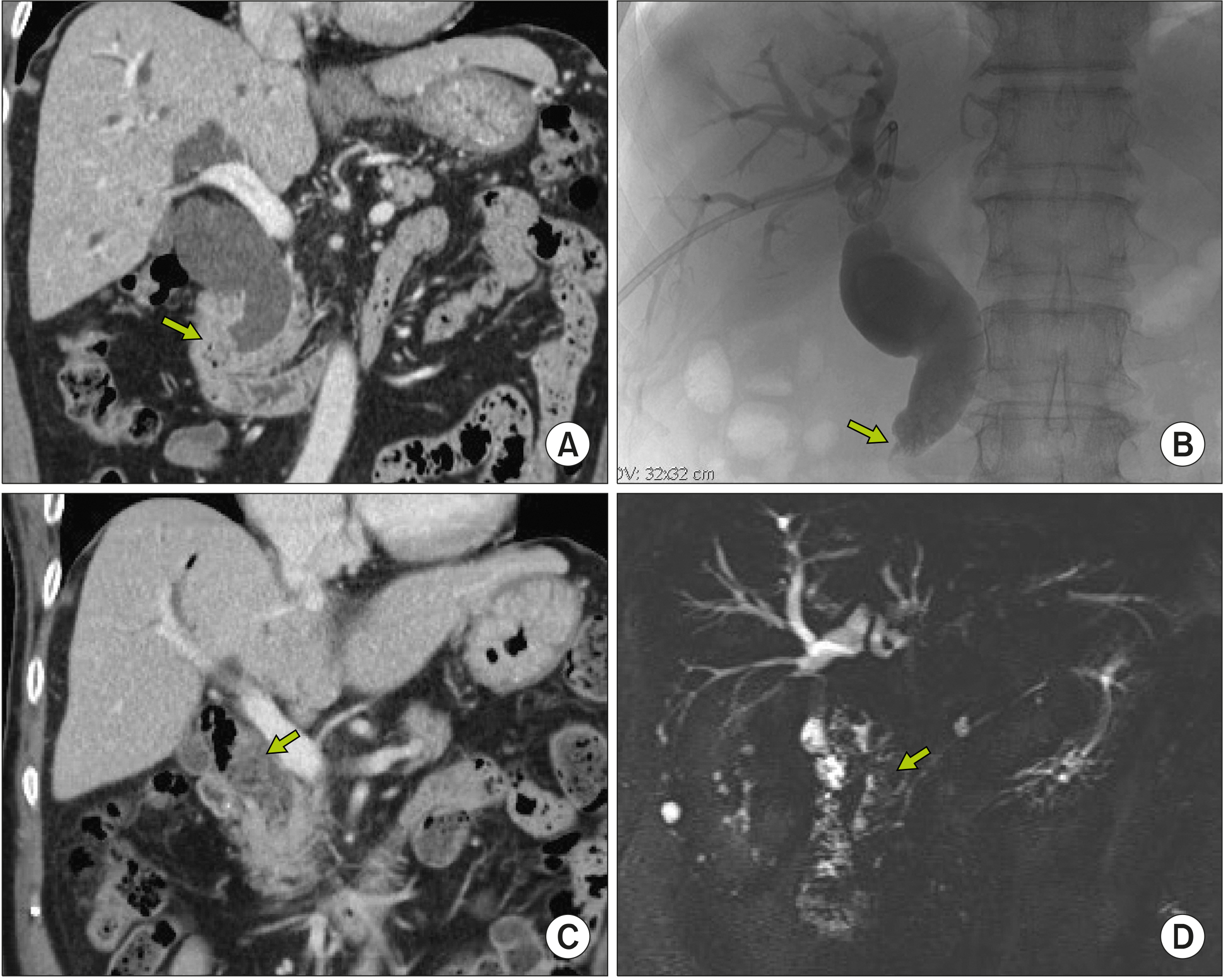

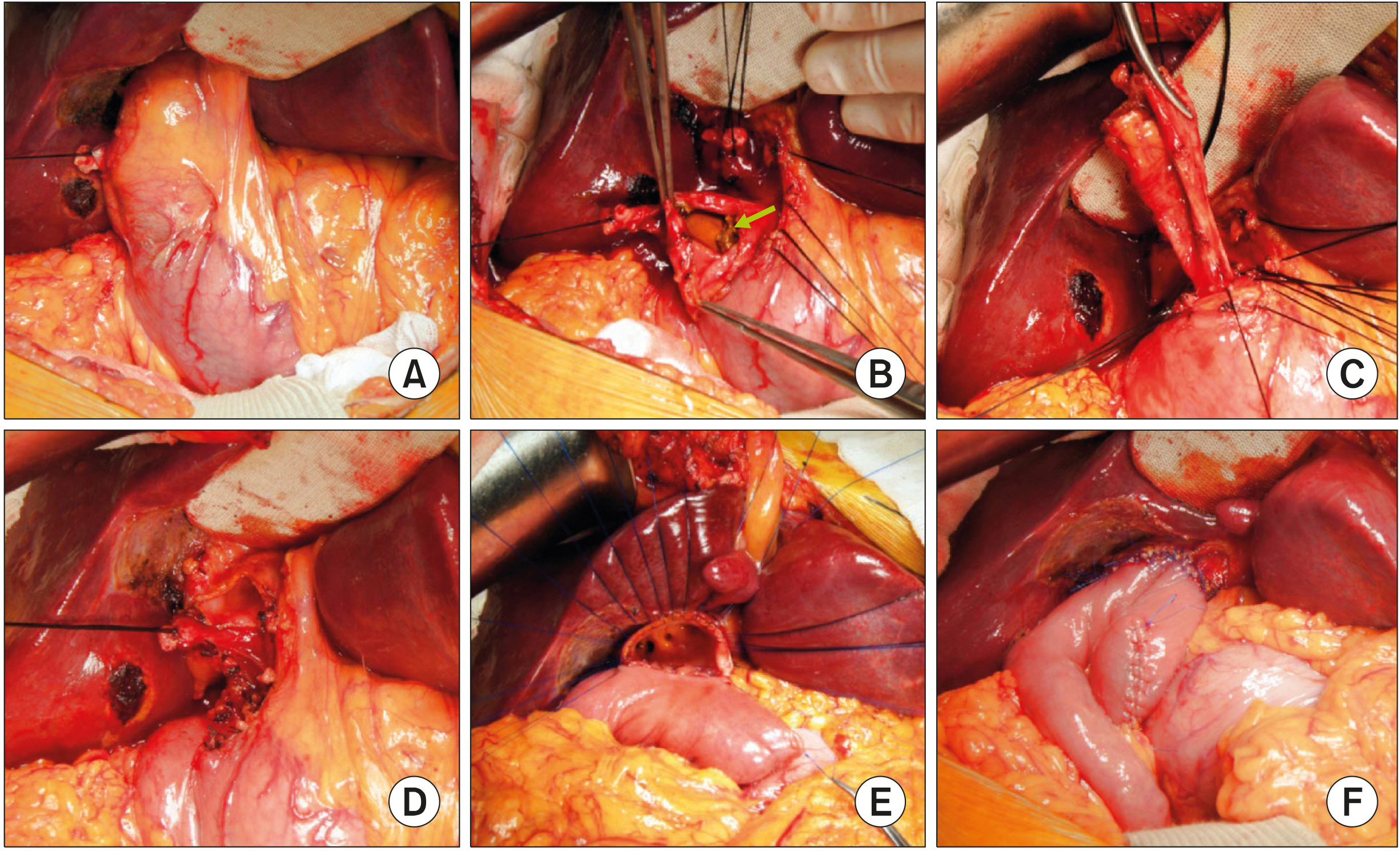

- Despite development in endoscopic treatment and minimally invasive surgery for choledocholithiasis, there remains a small number of patients who require bypass Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy (RYCJ) because of the intractable occurrence of common bile duct (CBD) stones. We herein present the detailed procedures of open RYCJ customized for intractable choledocholithiasis. The first method is a side-to-end choledochojejunostomy with intraluminal closure of the distal CBD. This method was applied to a 79-year-old female patient who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) more than 10 times in the past 14 years (Case No. 1). The distal CBD was explored through choledochotomy and then the distal CBD lumen was occluded with internal running sutures. A large-sized choledochojejunostomy was performed. The patient recovered uneventfully and has been doing well for the past 2 years. The second method is an end-to-end choledochojejunostomy with segmental CBD resection. It was applied to a 75-year-old male patient who underwent ERCP 9 times in the past 10 years (Case No. 2). The CBD was resected segmentally and a large-sized choledochojejunostomy was performed. The patient also recovered uneventfully and has been doing well for the past 2 years. In conclusion, the primary indication of bypass RYCJ is intractable choledocholithiasis which requires numerous sessions of endoscopic stone removal over a long period. Open RYCJ is the preferred procedure to date. If the papilla is patulous, the distal CBD should be occluded or resected to prevent reflux ascending cholangitis. We recommend to resect the intrapancreatic distal CBD if it is markedly dilated like choledochal cyst.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Costi R, Gnocchi A, Di Mario F, Sarli L. 2014; Diagnosis and management of choledocholithiasis in the golden age of imaging, endoscopy and laparoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 20:13382–13401. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i37.13382. PMID: 25309071. PMCID: PMC4188892.

Article2. Nathanson LK, O'Rourke NA, Martin IJ, Fielding GA, Cowen AE, Roberts RK, et al. 2005; Postoperative ERCP versus laparoscopic choledochotomy for clearance of selected bile duct calculi: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 242:188–192. DOI: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171035.57236.d7. PMID: 16041208. PMCID: PMC1357723.3. Urbach DR, Khajanchee YS, Jobe BA, Standage BA, Hansen PD, Swanstrom LL. 2001; Cost-effective management of common bile duct stones: a decision analysis of the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), intraoperative cholangiography, and laparoscopic bile duct exploration. Surg Endosc. 15:4–13. DOI: 10.1007/s004640000322. PMID: 11178753.4. Pring CM, Skelding-Millar L, Goodall RJ. 2005; Expectant treatment or cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for choledocholithiasis in patients over 80 years old? Surg Endosc. 19:357–360. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-004-9089-1. PMID: 15645324.

Article5. Maple JT, Ikenberry SO, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Decker GA, Early D, et al. 2011; The role of endoscopy in the management of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 74:731–744. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.012. PMID: 21951472.

Article6. Shim CS. 2010; How should biliary stones be managed? Gut Liver. 4:161–172. DOI: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.2.161. PMID: 20559517. PMCID: PMC2886934.

Article7. Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. 2000; Endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones in patients 90 years of age and older. Gastrointest Endosc. 52:187–191. DOI: 10.1067/mge.2000.107285. PMID: 10922089.

Article8. Moon JH, Cha SW, Ryu CB, Kim YS, Hong SJ, Cheon YK, et al. 2004; Endoscopic treatment of retained bile-duct stones by using a balloon catheter for electrohydraulic lithotripsy without cholangioscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 60:562–566. DOI: 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02012-7.

Article9. Sugiyama M, Suzuki Y, Abe N, Masaki T, Mori T, Atomi Y. 2004; Endoscopic retreatment of recurrent choledocholithiasis after sphincterotomy. Gut. 53:1856–1859. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2004.041020. PMID: 15542528. PMCID: PMC1774317.

Article10. Kadaba RS, Bowers KA, Khorsandi S, Hutchins RR, Abraham AT, Sarker SJ, et al. 2017; Complications of biliary-enteric anastomoses. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 99:210–215. DOI: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0293. PMID: 27659373. PMCID: PMC5450270.

Article11. Vogt DP, Hermann RE. 1981; Choledochoduodenostomy, choledochojejunostomy or sphincteroplasty for biliary and pancreatic disease. Ann Surg. 193:161–168. DOI: 10.1097/00000658-198102000-00006. PMID: 7469551. PMCID: PMC1345035.

Article12. Hori T, Aisu Y, Yamamoto M, Yasukawa D, Iida T, Yagi S, et al. 2019; Laparoscopic approach for choledochojejunostomy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 18:285–288. DOI: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2019.04.004. PMID: 31023579.

Article13. Hori T. 2019; Comprehensive and innovative techniques for laparoscopic choledocholithotomy: a surgical guide to successfully accomplish this advanced manipulation. World J Gastroenterol. 25:1531–1549. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i13.1531. PMID: 30983814. PMCID: PMC6452235.

Article14. Han HS, Yi NJ. 2004; Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy for benign biliary disease. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 14:80–84. DOI: 10.1097/00129689-200404000-00006. PMID: 15287605.

Article15. Ruurda JP, van Dongen KW, Dries J, Borel Rinkes IH, Broeders IA. 2003; Robot-assisted laparoscopic choledochojejunostomy. Surg Endosc. 17:1937–1942. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-003-9008-x. PMID: 14569457.

Article16. Benzie AL, Sucandy I, Spence J, Ross S, Rosemurgy A. 2019; Robotic choledochoduodenostomy for benign distal common bile duct stricture: how we do it. J Robot Surg. 13:713–716. DOI: 10.1007/s11701-019-00957-8. PMID: 30989618.

Article17. Misra SP, Dwivedi M. 2009; Reflux of duodenal contents and cholangitis in patients undergoing self-expanding metal stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 70:317–321. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.12.054. PMID: 19539920.

Article18. Hwang S, Ha TY, Song GW, Jung DH. 2016; Cluster hepaticojejunostomy with radial spreading anchoring traction technique for secure reconstruction of widely opened hilar bile ducts. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 20:66–70. DOI: 10.14701/kjhbps.2016.20.2.66. PMID: 27212993. PMCID: PMC4874047.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Study of Residual Stone in Choledocholithiasis

- A clinical review of choledocholithiasis

- Optimal Evaluation of Suspected Choledocholithiasis: Does This Patient Really Have Choledocholithiasis?

- Surgical Treatments of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

- 128 Cases of Endoscopic Sphincterotomy (EST)