J Korean Med Sci.

2021 May;36(18):e125. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e125.

Incidence and Direct Medical Cost of Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Korea: Based on National Health Insurance Service Claims Data from 2011 to 2017

- Affiliations

-

- 1OKmind Psychiatry Clinic, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Kangwon National University Hospital, Kangwon University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea

- 3Department of Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Physical Education, School of Education, Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea

- KMID: 2515858

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e125

Abstract

- Background

We aimed to investigate the annual incidence of trauma and stress-related mental disorder including acute stress disorder (ASD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) using the National Health Insurance Service Database. In addition, we estimated direct medical cost of ASD and PTSD in Korea.

Methods

To examine the incidence, we selected patients who had at least one medical claim containing a 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems code for ASD (F43.0) and PTSD (F43.1) and had not been diagnosed in the previous 360 days, from 2010 to 2017. We estimated annual incidence and the number of newly diagnosed patients of ASD and PTSD. Annual prevalence and direct medical cost of ASD and PTSD were also estimated.

Results

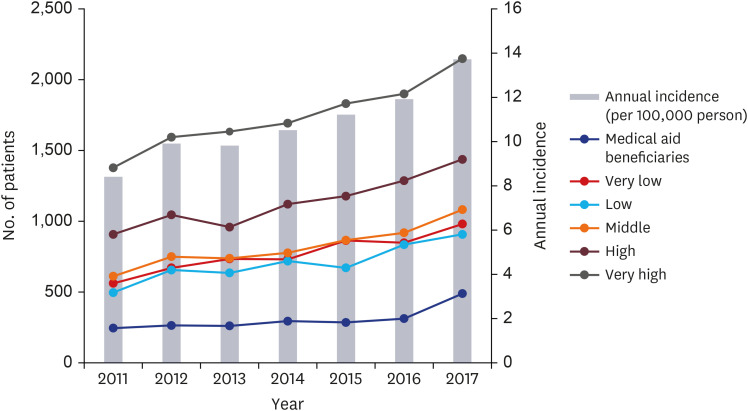

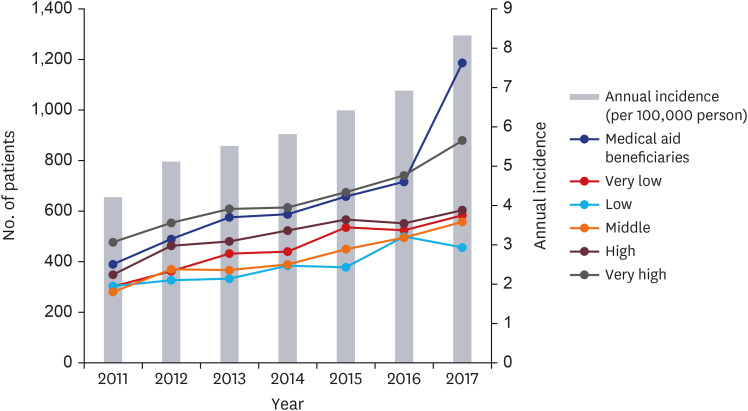

The number of newly diagnosed cases of ASD and PTSD from 2011 to 2017 totaled 38,298 and 21,402, respectively. The mean annual incidence of ASD ranged from 8.4 to 13.7 per 100,000 population and that of PTSD ranged from 4.2 to 8.3 per 100,000 population, respectively. The incidence of ASD was found more in females and was highest among the 70–79 years of age group and the self-employed individuals group. The incidence of PTSD was also more common in the female group. However, the incidence of PTSD was highest in the 60–69 years of age group and in the medical aid beneficiaries group. The annual estimated medical cost per person of ASD ranged from 104 to 149 US dollars (USD). In addition, that of PTSD ranged from 310 to 426 USD.

Conclusion

From 2011 to 2017, the annual incidence and direct medical cost of ASD and PTSD in Korea were increased. Proper information on ASD and PTSD will not only allows us to accumulate more knowledge about these disorders themselves but also lead to more appropriate therapeutic interventions by improving the ability to cope with these trauma related psychiatric sequelae.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Association;2013.2. Cahill SP, Pontoski K. Post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder I: their nature and assessment considerations. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005; 2(4):14–25.3. Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press;2008.4. National Comorbidity Survey (NCS). Updated 2007. Accessed September 22, 2020. https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/index.php.5. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62(6):617–627. PMID: 15939839.

Article6. Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010; 49(10):980–989. PMID: 20855043.

Article7. Ferry FR, Brady SE, Bunting BP, Murphy SD, Bolton D, O'Neill SM. The economic burden of PTSD in Northern Ireland. J Trauma Stress. 2015; 28(3):191–197. PMID: 25990825.

Article8. Hong JP, Lee DW, Ham BJ, Lee SH, Sung SJ, Yoon T, et al. The Survey of Mental Disorders in Korea 2016. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2017.9. Dai W, Chen L, Lai Z, Li Y, Wang J, Liu A. The incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder among survivors after earthquakes:a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2016; 16(1):188. PMID: 27267874.

Article10. Chen L, Liu A. The incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder after floods: a meta-analysis. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2015; 9(3):329–333. PMID: 25857395.

Article11. Cameron KL, Sturdivant RX, Baker SP. Trends in the incidence of physician-diagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder among active-duty U.S. military personnel between 1999 and 2008. Mil Med Res. 2019; 6(1):8. PMID: 30905323.

Article12. Ophuis RH, Olij BF, Polinder S, Haagsma JA. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder and depression following violence related injury treated at the emergency department: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018; 18(1):311. PMID: 30253782.

Article13. Fink DS, Cohen GH, Sampson LA, Gifford RK, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, et al. Incidence of and risk for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in a representative sample of US Reserve and National Guard. Ann Epidemiol. 2016; 26(3):189–197. PMID: 26907538.

Article14. Ward MM. Estimating disease prevalence and incidence using administrative data: some assembly required. J Rheumatol. 2013; 40(8):1241–1243. PMID: 23908527.

Article15. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Association;1994.16. Buljan NF. Burden of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) - health, social, and economic impacts of exposure to the London bombings [dissertation]. London: London School of Economics and Political Science;2015.17. Wang L, Li L, Zhou X, Pandya S, Baser O. A real-world evaluation of the clinical and economic burden of united states veteran patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. Value Health. 2016; 19(7):PA524.

Article18. Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Chen L, Duhig AM, Dayoub EJ, Kantor ES, et al. Cost of post-traumatic stress disorder vs major depressive disorder among patients covered by medicaid or private insurance. Am J Manag Care. 2011; 17(8):e314–23. PMID: 21851139.19. Bothe T, Jacob J, Kröger C, Walker J. How expensive are post-traumatic stress disorders? Estimating incremental health care and economic costs on anonymised claims data. Eur J Health Econ. 2020; 21(6):917–930. PMID: 32458163.

Article20. Meredith LS, Eisenman DP, Han B, Green BL, Kaltman S, Wong EC, et al. Impact of collaborative care for underserved patients with PTSD in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2016; 31(5):509–517. PMID: 26850413.

Article21. Cheol Seong S, Kim YY, Khang YH, Heon Park J, Kang HJ, Lee H, et al. Data resource profile: the National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46(3):799–800. PMID: 27794523.

Article22. World Health Organization. ICD-10: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision, 2nd ed. Updated 2020. Accessed September 30, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42980.23. Ministry of Economy and Finance. Currency exchange statistical survey. Updated 2020. Accessed September 30, 2020. http://www.index.go.kr/potal/stts/idxMain/selectPoSttsIdxSearch.do?idx_cd=1068.24. Kwon SJ. Disaster psychological treatment attracting attention after the Sewol ferry accident. Updated 2014. Accessed September 30, 2020. http://monthly.chosun.com/Client/News/viw.asp?ctcd=C&nNewsNumb=201406100017.25. Park JI, Jeon M. The stigma of mental illness in Korea. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2016; 55(4):299–309.

Article26. Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, et al. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress. Washington, D.C., USA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families;2010.27. Santiago CD, Kaltman S, Miranda J. Poverty and mental health: how do low-income adults and children fare in psychotherapy? J Clin Psychol. 2013; 69(2):115–126. PMID: 23280880.

Article28. Pabayo R, Fuller D, Goldstein RB, Kawachi I, Gilman SE. Income inequality among American states and the conditional risk of post-traumatic stress disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017; 52(9):1195–1204. PMID: 28667485.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Incidence and Direct Medical Cost of Adjustment Disorder and in Korea Using National Health Insurance Service Claims Data From 2011 to 2017

- Plasma Homovanillic Acid Level in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- Plasma Serotonin Level in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- Impact of Environmental Stressors on the Risk for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Quality of Life in Intensive Care Unit Survivors