J Korean Med Sci.

2021 May;36(17):e103. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e103.

Towards Telemedicine Adoption in Korea: 10 Practical Recommendations for Physicians

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medical Informatics, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 2Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2515802

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e103

Abstract

- Due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, consultation and prescription via telemedicine were temporarily allowed in the Korean population. However, at this point, it is difficult to determine whether telemedicine fulfills its role as a health care strategy. Arguably, if we had enough previous experience with telemedicine or sufficient preparation for its application, telemedicine could be more smoothly and flexibly adopted in the medical field. As it is still not possible to predict when the COVID-19 pandemic will end, phone consultation and prescription are likely to continue for some time. Hence, it is expected that telemedicine will naturally settle in the medical field in the near future. However, as we have noticed during this outbreak, improvised telemedicine without adequate guidance can be confusing to both patients and health professionals, thus reducing the benefit to patients. Medical staff requires preparation on how to appropriately use telemedicine. Thus, here we present some suggestions on implementing and preparing for telemedicine in the medical community.

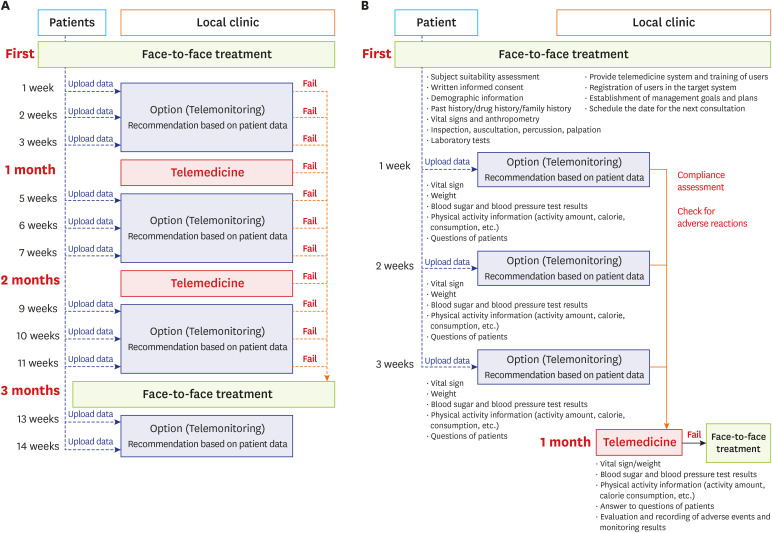

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Expectations and concerns regarding medical advertisements via large commercial medical platform advertising companies: a legal perspective

Raeun Kim, Hakyoung Park, Jiwon Shinn, Hun-Sung Kim

Cardiovasc Prev Pharmacother. 2024;6(2):48-56. doi: 10.36011/cpp.2024.6.e8.

Reference

-

1. Kim HS, Kim H, Lee S, Lee KH, Kim JH. Current clinical status of telehealth in Korea: categories, scientific basis, and obstacles. Healthc Inform Res. 2015; 21(4):244–250. PMID: 26618030.

Article2. Kim HS, Cho JH, Yoon KH. New directions in chronic disease management. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2015; 30(2):159–166. PMID: 26194075.

Article3. Velavan TP, Meyer CG. The COVID-19 epidemic. Trop Med Int Health. 2020; 25(3):278–280. PMID: 32052514.

Article4. Temporary allowance of telephone consultation/prescription and proxy prescription. Updated 2020. Accessed March 10, 2020. http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0101vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=040102&CONT_SEQ=353269.5. Kim HS. Lessons from temporary telemedicine initiated owing to outbreak of COVID-19. Healthc Inform Res. 2020; 26(2):159–161. PMID: 32547813.

Article6. Bae TW, Kwon KK, Kim KH. Mass infection analysis of COVID-19 using the SEIRD model in Daegu-Gyeongbuk of Korea from April to May, 2020. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(34):e317. PMID: 32864913.

Article7. Noh J, Chang HH, Jeong IK, Yoon KH. Coronavirus disease 2019 and diabetes: the epidemic and the Korean diabetes association perspective. Diabetes Metab J. 2020; 44(3):372–381. PMID: 32613777.

Article8. Kim HS, Sun C, Yang SJ, Sun L, Li F, Choi IY, et al. Randomized, open-label, parallel group study to evaluate the effect of internet-based glucose management system on subject with diabetes in China. Telemed J E Health. 2016; 22(8):666–674. PMID: 26938489.9. Ferguson CM. Inspection, auscultation, palpation, and percussion of the abdomen. In : Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Boston, MA, USA: Butterworths;1990.10. Yeston NS. Inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation = connection. Conn Med. 2002; 66(12):757–758. PMID: 12532611.11. Kim HS, Lee KH, Kim H, Kim JH. Using mobile phones in healthcare management for the elderly. Maturitas. 2014; 79(4):381–388. PMID: 25270725.

Article12. Kim HS. Decision-making in artificial intelligence: is it always correct? J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(1):e1. PMID: 31898430.

Article13. Kim HS, Hwang Y, Lee JH, Oh HY, Kim YJ, Kwon HY, et al. Future prospects of health management systems using cellular phones. Telemed J E Health. 2014; 20(6):544–551. PMID: 24693986.

Article14. McGrail KM, Ahuja MA, Leaver CA. Virtual visits and patient-centered care: results of a patient survey and observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2017; 19(5):e177. PMID: 28550006.

Article15. Sun C, Sun L, Xi S, Zhang H, Wang H, Feng Y, et al. Mobile phone-based telemedicine practice in older chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019; 7(1):e10664. PMID: 30609983.

Article16. Kim HS, Yoon KH. Lessons from use of continuous glucose monitoring systems in digital healthcare. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2020; 35(3):541–548. PMID: 32981296.

Article17. Segura Anaya LH, Alsadoon A, Costadopoulos N, Prasad PW. Ethical implications of user perceptions of wearable devices. Sci Eng Ethics. 2018; 24(1):1–28. PMID: 28155094.

Article18. Odhiambo R, Mars M. Patients' understanding of telemedicine terms required for informed consent when translated into Kiswahili. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18(1):588. PMID: 29720139.

Article19. Nittari G, Khuman R, Baldoni S, Pallotta G, Battineni G, Sirignano A, et al. Telemedicine practice: review of the current ethical and legal challenges. Telemed J E Health. 2020; 26(12):1427–1437. PMID: 32049608.

Article20. Gordon EJ. When oral consent will do. Field Methods. 2000; 12(3):235–238.

Article21. Cho JH, Choi YH, Kim HS, Lee JH, Yoon KH. Effectiveness and safety of a glucose data-filtering system with automatic response software to reduce the physician workload in managing type 2 diabetes. J Telemed Telecare. 2011; 17(5):257–262. PMID: 21628421.

Article22. Cho JH, Kim HS, Yoon KH, Son HY. Are information technology-based systems the way forward for diabetes management in Asia? J Diabetes Investig. 2013; 4(1):1–3.

Article23. Omboni S, Caserini M, Coronetti C. Telemedicine and M-health in hypertension management: technologies, applications and clinical evidence. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2016; 23(3):187–196. PMID: 27072129.

Article24. Singh J, Keer N. Overview of telemedicine and sleep disorders. Sleep Med Clin. 2020; 15(3):341–346. PMID: 32762967.

Article25. Kim HS, Choi W, Baek EK, Kim YA, Yang SJ, Choi IY, et al. Efficacy of the smartphone-based glucose management application stratified by user satisfaction. Diabetes Metab J. 2014; 38(3):204–210. PMID: 25003074.

Article26. Broens TH, Huis in't Veld RM, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, Hermens HJ, van Halteren AT, Nieuwenhuis LJ. Determinants of successful telemedicine implementations: a literature study. J Telemed Telecare. 2007; 13(6):303–309. PMID: 17785027.

Article27. Lazzara EH, Benishek LE, Patzer B, Gregory ME, Hughes AM, Heyne K, et al. Utilizing telemedicine in the trauma intensive care unit: does it impact teamwork? Telemed J E Health. 2015; 21(8):670–676. PMID: 25885369.

Article28. Kim HS, Shin JA, Chang JS, Cho JH, Son HY, Yoon KH. Continuous glucose monitoring: current clinical use. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012; 28(Suppl 2):73–78. PMID: 23280870.

Article29. Rosen D, McCall JD, Primack BA. Telehealth protocol to prevent readmission among high-risk patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Med. 2017; 130(11):1326–1330. PMID: 28756266.

Article30. May C, Ellis NT. When protocols fail: technical evaluation, biomedical knowledge, and the social production of ‘facts’ about a telemedicine clinic. Soc Sci Med. 2001; 53(8):989–1002. PMID: 11556780.

Article31. Huskamp HA, Busch AB, Souza J, Uscher-Pines L, Rose S, Wilcock A, et al. How is telemedicine being used in opioid and other substance use disorder treatment? Health Aff (Millwood). 2018; 37(12):1940–1947. PMID: 30633671.

Article32. Pepin D, Hulkower R, McCord RF. How are telehealth laws intersecting with laws addressing the opioid overdose epidemic? J Public Health Manag Pract. 2020; 26(3):227–231. PMID: 31348152.

Article33. Omboni S. Telemedicine during the COVID-19 in Italy: a missed opportunity? Telemed J E Health. 2020; 26(8):973–975. PMID: 32324109.

Article34. Cho JH, Chang SA, Kwon HS, Choi YH, Ko SH, Moon SD, et al. Long-term effect of the Internet-based glucose monitoring system on HbA1c reduction and glucose stability: a 30-month follow-up study for diabetes management with a ubiquitous medical care system. Diabetes Care. 2006; 29(12):2625–2631. PMID: 17130195.

Article35. Chen S, Cheng A, Mehta K. A review of telemedicine business models. Telemed J E Health. 2013; 19(4):287–297. PMID: 23540278.

Article36. Jung AR, Park JI, Kim HS. Physical activity for prevention and management of sleep disturbances. Sleep Med Rev. 2020; 11(1):15–18.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Survey study of telemedicine-experienced physicians on the acceptability of telemedicine: using propensity score matching method

- A debate about telemedicine in South Korea

- Pediatricians’ perspectives on telemedicine for pediatric patients

- Key Aspects of Using Web-based Diabetes Telemedicine Systems in Multiple Clinical Settings

- Telemedicine in the U.S.A. with Focus on Clinical Applications and Issues