Ann Clin Neurophysiol.

2021 Apr;23(1):29-34. 10.14253/acn.2021.23.1.29.

Nomenclature of emerging therapeutics in neurology

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurology, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan, Korea

- 2Department of Neurology, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea

- KMID: 2515605

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14253/acn.2021.23.1.29

Abstract

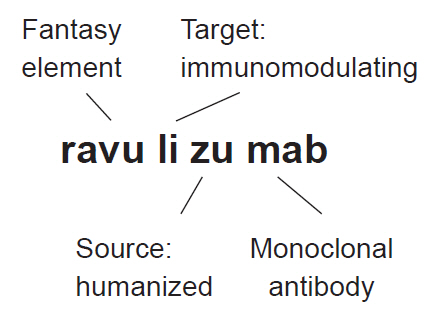

- New therapeutics in neurology are expanding at an unprecedented pace. In addition to the classic enzyme-replacement therapies, monoclonal antibodies are increasingly being used to modulate autoimmunity. RNA therapeutics are an emerging class, together with gene and cell therapies. The nomenclature of international nonproprietary names helps us to recognize these new drugs according to their class and function. Suffixes denote major categories of the drug, while infixes provide additional information such as the source and target.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Robertson JS, Chui WK, Genazzani AA, Malan SF, López de la Rica Manjavacas A, Mignot G, et al. The INN global nomenclature of biological medicines: a continuous challenge. Biologicals. 2019; 60:15–23.

Article2. Jerome JB, Sagon P. The USAN nomenclature system. JAMA. 1975; 232:294–299.

Article3. Leader B, Baca QJ, Golan DE. Protein therapeutics: a summary and pharmacological classification. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008; 7:21–39.

Article4. Mohammadi E, Seyedhosseini-Ghaheh H, Mahnam K, Jahanian-Najafabadi A, Mir Mohammad Sadeghi H. Reteplase: structure, function, and production. Adv Biomed Res. 2019; 8:19.

Article5. Blom D, Speijer D, Linthorst GE, Donker-Koopman WG, Strijland A, Aerts JM. Recombinant enzyme therapy for Fabry disease: absence of editing of human alpha-galactosidase A mRNA. Am J Hum Genet. 2003; 72:23–31.6. Babaesfahani A, Bajaj T. Glatiramer. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing;2020.7. Mayrhofer P, Kunert R. Nomenclature of humanized mAbs: early concepts, current challenges and future perspectives. Hum Antibodies. 2019; 27:37–51.

Article8. Grillo-López AJ, White CA, Varns C, Shen D, Wei A, McClure A, et al. Overview of the clinical development of rituximab: first monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of lymphoma. Semin Oncol. 1999; 26(5 Suppl 14):66–73.9. Frenzel A, Schirrmann T, Hust M. Phage display-derived human antibodies in clinical development and therapy. MAbs. 2016; 8:1177–1194.

Article10. Raffaelli B, Mussetto V, Israel H, Neeb L, Reuter U. Erenumab and galcanezumab in chronic migraine prevention: effects after treatment termination. J Headache Pain. 2019; 20:66.

Article11. Wang F, Zuroske T, Watts JK. RNA therapeutics on the rise. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020; 19:441–442.

Article12. Mendell JR, Khan N, Sha N, Eliopoulos H, McDonald CM, Goemans N, et al. Comparison of long-term ambulatory function in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy treated with eteplirsen and matched natural history controls. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2021; Feb. 19. [Epub]. DOI:10.3233/JND-200548.

Article13. Clemens PR, Rao VK, Connolly AM, Harper AD, Mah JK, Smith EC, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of viltolarsen in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy amenable to Exon 53 skipping: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020; 77:982–991.14. Anwar S, Yokota T. Golodirsen for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Drugs Today (Barc). 2020; 56:491–504.

Article15. Mercuri E, Darras BT, Chiriboga CA, Day JW, Campbell C, Connolly AM, et al. Nusinersen versus Sham control in later-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:625–635.

Article16. Benson MD, Waddington-Cruz M, Berk JL, Polydefkis M, Dyck PJ, Wang AK, et al. Inotersen treatment for patients with hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:22–31.17. Adams D, Gonzalez-Duarte A, O’Riordan WD, Yang CC, Ueda M, Kristen AV, et al. Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic, for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:11–21.18. Keeler AM, Flotte TR. Recombinant adeno-associated virus gene therapy in light of luxturna (and Zolgensma and Glybera): where are we, and how did we get here? Annu Rev Virol. 2019; 6:601–621.

Article19. Mendell JR, Al-Zaidy S, Shell R, Arnold WD, Rodino-Klapac LR, Prior TW, et al. Single-dose gene-replacement therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:1713–1722.

Article20. Oh KW, Moon C, Kim HY, Oh SI, Park J, Lee JH, et al. Phase I trial of repeated intrathecal autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015; 4:590–597.

Article21. Roskoski R Jr. Properties of FDA-approved small molecule protein kinase inhibitors: a 2021 update. Pharmacol Res. 2021; 165:105463.

Article22. Campagne O, Yeo KK, Fangusaro J, Stewart CF. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of selumetinib. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2021; 60:283–303.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A new Korean nomenclature for steatotic liver disease: Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Nomenclature Revision Consensus Task Force on behalf of the Korean Association for the Study of the Liver (KASL)

- Digital Therapeutics: Emerging New Therapy for Neurologic Deficits after Stroke

- Erratum: Correction of Nomenclature of Mutations

- Emerging and Promising Keywords in Biomolecules and Therapeutics for 21st Century Diseases

- A New Korean Nomenclature for Steatotic Liver Disease