J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Apr;36(16):e99. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e99.

Combined Effects of Depression and Chronic Disease on the Risk of Mortality: The Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (2006-2016)

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Family Medicine, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- KMID: 2515083

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e99

Abstract

- Background

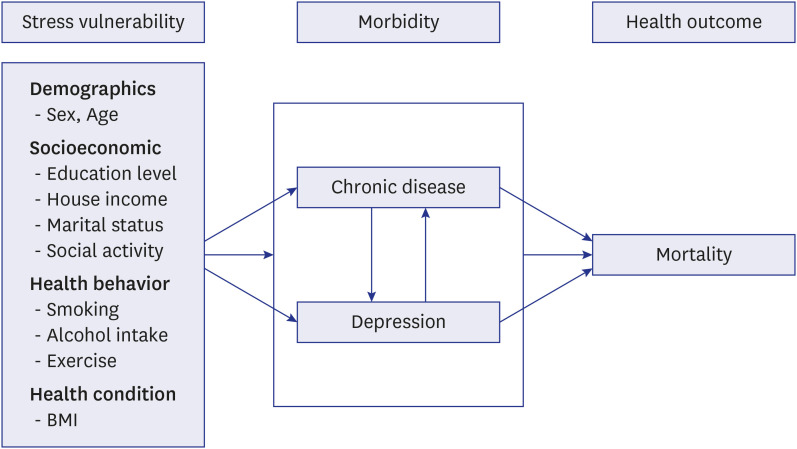

The prevalence of depression is much higher in people with chronic disease than in the general population. Depression exacerbates existing physical conditions, resulting in a higher-than-expected death rate from the physical condition itself. In our aging society, the prevalence of multimorbid patients is expected to increase; the resulting mental problems, especially depression, should be considered. Using a large-scale cohort from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA), we analyzed the combined effects of depression and chronic disease on all-cause mortality.

Methods

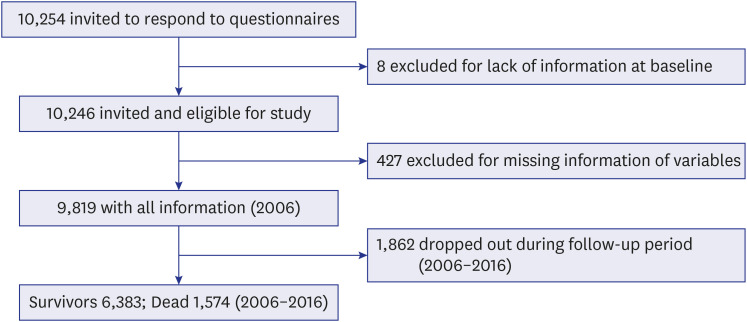

We analyzed 10-year (2006–2016) longitudinal data of 9,819 individuals who took part in the KLoSA, a nationwide survey of people aged 45–79 years. We examined the association between multimorbidity and depression using chi-square test and logistic regression. We used the Cox proportional hazard model to determine the combined effects of multimorbidity and depression on the all-cause mortality risk.

Results

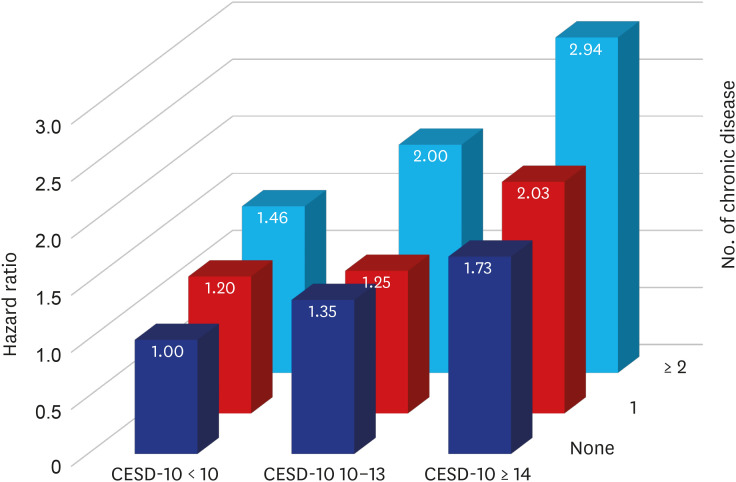

During the 10-year follow up, 1,574 people (16.0%) died. The hazard ratio associated with mild depression increased from 1.35 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.05–1.73) for no chronic disease to 1.25 (95% CI, 0.98–1.60) for 1 chronic disease, and to 2.00 (95% CI, 1.58–2.52) for multimorbidity. The hazard ratio associated with severe depression increased from 1.73 (95% CI, 1.33–2.24) for no chronic disease, to 2.03 (95% CI, 1.60–2.57) for 1 chronic disease, and to 2.94 (95% CI, 2.37–3.65) for multimorbidity.

Conclusion

Patients with coexisting multimorbidity and depression are at an increased risk of all-cause mortality than those with chronic disease or depression alone.

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2017.2. Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust. 2009; 190(S7):S54–60. PMID: 19351294.

Article3. Egede LE. Major depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007; 29(5):409–416. PMID: 17888807.

Article4. Aragonès E, Piñol JL, Labad A. Depression and physical comorbidity in primary care. J Psychosom Res. 2007; 63(2):107–111. PMID: 17662745.

Article5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's Welfare 2015. Australia's Welfare Series No. 12. Cat. No. AUS 189. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare;2015.6. van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Roos S, Knottnerus JA. Problems in determining occurrence rates of multimorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001; 54(7):675–679. PMID: 11438407.

Article7. Britt HC, Harrison CM, Miller GC, Knox SA. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Australia. Med J Aust. 2008; 189(2):72–77. PMID: 18637770.

Article8. Seeds PM, Dozois DJ. Prospective evaluation of a cognitive vulnerability-stress model for depression: the interaction of schema self-structures and negative life events. J Clin Psychol. 2010; 66(12):1307–1323. PMID: 20715020.

Article9. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989; 44(3):513–524. PMID: 2648906.

Article10. Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, Pike CT, Kessler RC. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015; 76(2):155–162. PMID: 25742202.

Article11. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006; 3(11):e442. PMID: 17132052.

Article12. Kim H, Park SM, Jang SN, Kwon S. Depressive symptoms, chronic medical illness, and health care utilization: findings from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA). Int Psychogeriatr. 2011; 23(8):1285–1293. PMID: 21418721.

Article13. Cho MJ, Lee JY. Epidemiology of depressive disorders in Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2005; 2(1):22–27.14. Cho MJ, Seong SJ, Park JE, Chung IW, Lee YM, Bae A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV mental disorders in South Korean adults: the Korean epidemiologic catchment area study 2011. Psychiatry Investig. 2015; 12(2):164–170.

Article15. Shin C, Kim Y, Park S, Yoon S, Ko YH, Kim YK, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depression in general population of Korea: results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2014. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32(11):1861–1869. PMID: 28960042.

Article16. Kinser PA, Lyon DE. A conceptual framework of stress vulnerability, depression, and health outcomes in women: potential uses in research on complementary therapies for depression. Brain Behav. 2014; 4(5):665–674. PMID: 25328843.

Article17. Cho MJ, Kim KH. Use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale in Korea. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998; 186(5):304–310. PMID: 9612448.

Article18. Cho MJ, Kim KH. Diagnostic validity of the CES-D (Korean version) in the assessment of DSM-III-R major depression. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1993; 32(3):381–399.19. Shin S. Validity study of short forms of the Korean version Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [Unpublished master's thesis]. Seoul, Korea: Seoul National University;2011.

Article20. Zhang W, O'Brien N, Forrest JI, Salters KA, Patterson TL, Montaner JS, et al. Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One. 2012; 7(7):e40793. PMID: 22829885.

Article21. Cartierre N, Coulon N, Demerval R. Confirmatory factor analysis of the short French version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression Scale (CES-D10) in adolescents. Encephale. 2011; 37(4):273–277. PMID: 21981887.22. Kim EM, Kim SH, Lee GH, Kim YA. Socioeconomic vulnerability, mental health, and their combined effects on all-cause mortality in Koreans, over 45 years: analysis of Korean longitudinal study of aging from 2006 to 2014. Korean J Fam Med. 2019; 40(4):227–234. PMID: 31344995.

Article23. Jun ER, Kim SH, Cho YJ, Kim YA, Lee JY. The influence of negative mental health on the health behavior and the mortality risk: analysis of Korean longitudinal study of aging from 2006 to 2014. Korean J Fam Med. 2019; 40(5):297–306. PMID: 31505911.

Article24. Kim S, Ryu E. Control effect of illness perception on depression and quality of life in patients with hemodialysis: using structural equation modeling. J Korean Biol Nurs Sci. 2018; 20(4):221–227.

Article25. Sin MK, Ibarra B, Tae T, Murphy PJ. Effect of a randomized controlled trial walking program on walking, stress, depressive symptoms and cardiovascular biomarkers in elderly Korean immigrants. J Korean Biol Nurs Sci. 2015; 17(2):89–96.

Article26. Jeon GS, You SJ, Kim MG, Kim YM, Cho SI. Psychometric properties of the Korean version of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory in Korean homecare workers for older adults. PLoS One. 2019; 14(8):e0221323. PMID: 31454378.

Article27. Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994; 10(2):77–84. PMID: 8037935.28. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977; 1(3):385–401.29. Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Arch Intern Med. 1999; 159(15):1701–1704. PMID: 10448771.30. Nicholson A, Kuper H, Hemingway H. Depression as an aetiologic and prognostic factor in coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of 6362 events among 146 538 participants in 54 observational studies. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27(23):2763–2774. PMID: 17082208.

Article31. Kronish IM, Rieckmann N, Schwartz JE, Schwartz DR, Davidson KW. Is depression after an acute coronary syndrome simply a marker of known prognostic factors for mortality? Psychosom Med. 2009; 71(7):697–703. PMID: 19592517.

Article32. Davidson KW, Burg MM, Kronish IM, Shimbo D, Dettenborn L, Mehran R, et al. Association of anhedonia with recurrent major adverse cardiac events and mortality 1 year after acute coronary syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010; 67(5):480–488. PMID: 20439829.

Article33. Lespérance F, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Five-year risk of cardiac mortality in relation to initial severity and one-year changes in depression symptoms after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002; 105(9):1049–1053. PMID: 11877353.

Article34. Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Juneau M, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Gender, depression, and one-year prognosis after myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 1999; 61(1):26–37. PMID: 10024065.

Article35. Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F. Depression and other psychological risks following myocardial infarction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003; 60(6):627–636. PMID: 12796226.

Article36. Khawaja IS, Westermeyer JJ, Gajwani P, Feinstein RE. Depression and coronary artery disease: the association, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Psychiatry (Edgmont Pa). 2009; 6(1):38–51.37. de Jonge P, Mangano D, Whooley MA. Differential association of cognitive and somatic depressive symptoms with heart rate variability in patients with stable coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Psychosom Med. 2007; 69(8):735–739. PMID: 17942844.

Article38. Ziegelstein RC, Parakh K, Sakhuja A, Bhat U. Depression and coronary artery disease: is there a platelet link? Mayo Clin Proc. 2007; 82(11):1366–1368. PMID: 17976357.

Article39. Brown ES, Varghese FP, McEwen BS. Association of depression with medical illness: does cortisol play a role? Biol Psychiatry. 2004; 55(1):1–9. PMID: 14706419.

Article40. Brouwers C, Mommersteeg PM, Nyklíček I, Pelle AJ, Westerhuis BL, Szabó BM, et al. Positive affect dimensions and their association with inflammatory biomarkers in patients with chronic heart failure. Biol Psychol. 2013; 92(2):220–226. PMID: 23085133.

Article41. Timonen M, Laakso M, Jokelainen J, Rajala U, Meyer-Rochow VB, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S. Insulin resistance and depression: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2005; 330(7481):17–18. PMID: 15604155.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Socioeconomic Vulnerability, Mental Health, and Their Combined Effects on All-Cause Mortality in Koreans, over 45 Years: Analysis of Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging from 2006 to 2014

- The Influence of Negative Mental Health on the Health Behavior and the Mortality Risk: Analysis of Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging from 2006 to 2014

- Association between Personal Encounters and Incidence of Depression in Korean Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults: Result from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging

- Influence of Social Engagement on Mortality in Korea: Analysis of the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (2006-2012)

- Antiaging and Exercise