J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Mar;36(10):e72. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e72.

Early Trauma and Relationships among Recent Stress, Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation in Korean Women

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Psychiatry, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Seoul Metropolitan Eunpyeong Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Busan Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea

- 4Department of Psychiatry, Wonkwang University Hospital, Iksan, Korea

- 5Department of Psychiatry, Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Cheonan, Korea

- 6Department of Neuropsychiatry, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Bucheon, Korea

- 7Department of Psychiatry, Kyung Hee University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 8Department of Psychiatry, Gachon University Gil Medical Center, Incheon, Korea

- 9Department of Psychiatry, Wonju Severance Christian Hospital, Wonju, Korea

- 10Department of Psychology, College of Social Sciences, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea

- 11Department of Psychiatry, Depression Center, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 12Department of Neuropsychiatry, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 13Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2513709

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e72

Abstract

- Background

Evidence continues to accumulate that the presence or absence of early trauma (ET) implies unique characteristics in the relationships between suicidal ideation and its risk factors. We examined the relationships among recent stress, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and suicidal ideation in Korean suicidal women with or without such a history.

Methods

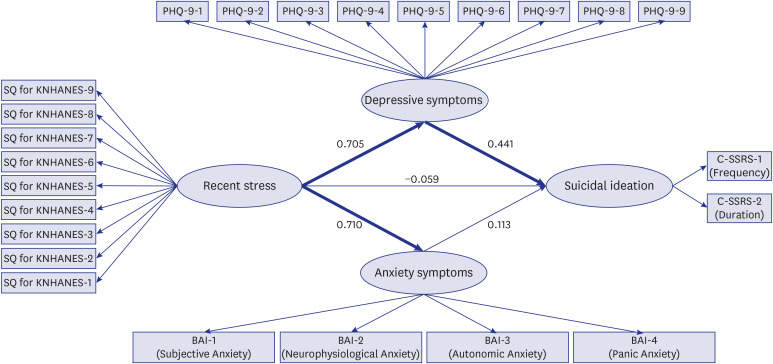

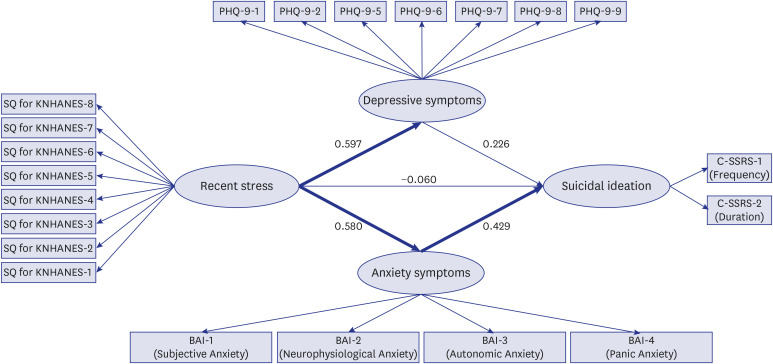

Using data on suicidal adult females, 217 victims and 134 non-victims of ET, from the Korean Cohort for the Model Predicting a Suicide and Suicide-related Behavior, we performed structural equation modeling to investigate the contribution of recent stress, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms on suicidal ideation within each group according to the presence or absence of a history of ET.

Results

Structural equation modeling with anxiety and depressive symptoms as potential mediators showed a good fit. Recent stress had a direct effect on both depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms in both groups. Only anxiety symptoms for victims of ET (standardized regression weight, 0.281; P = 0.005) and depressive symptoms for non-victims of ET (standardized regression weight, 0.326; P = 0.003) were full mediators that increased suicidal ideation. Thus, stress contributed to suicidal ideation by increasing the level of anxiety and depressive symptoms for victims and non-victims, respectively.

Conclusion

Tailored strategies to reduce suicidal ideation should be implemented according to group type, victims or non-victims of ET. Beyond educating suicidal women in stressmanagement techniques, it would be effective to decrease anxiety symptoms for those with a history of ET and decrease depressive symptoms for those without such a history.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Neeleman J, de Graaf R, Vollebergh W. The suicidal process; prospective comparison between early and later stages. J Affect Disord. 2004; 82(1):43–52. PMID: 15465575.

Article2. Sokero P. Suicidal ideation and attempt among psychiatric patients with major depressive disorder. Updated 2006. Accessed September 25, 2020. https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/78764/2006a13.pdf;sequence=1.3. Beck AT, Steer RA, Beck JS, Newman CF. Hopelessness, depression, suicidal ideation, and clinical diagnosis of depression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1993; 23(2):139–145. PMID: 8342213.

Article4. Rudd MD. An integrative model of suicidal ideation. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1990; 20(1):16–30. PMID: 2336679.5. Vilhjálmsson R, Kristjansdottir G, Sveinbjarnardottir E. Factors associated with suicide ideation in adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998; 33(3):97–103. PMID: 9540383.6. Hirsch JK, Duberstein PR, Unützer J. Chronic medical problems and distressful thoughts of suicide in primary care patients: mitigating role of happiness. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009; 24(7):671–679. PMID: 19145577.

Article7. Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2001; 49(12):1023–1039. PMID: 11430844.

Article8. Cui Y, Kim SW, Lee BJ, Kim JJ, Yu JC, Lee KY, et al. Negative schema and rumination as mediators of the relationship between childhood trauma and recent suicidal ideation in patients with early psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019; 80(3):17m12088.

Article9. Park CH, Lee JW, Lee SY, Shim SH, Moon JJ, Paik JW, et al. Implications of increased trait impulsivity on psychopathology and experienced stress in the victims of early trauma with suicidality. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018; 206(11):840–849. PMID: 30371638.

Article10. Muzik M, Brier Z, Menke RA, Davis MT, Sexton MB. Longitudinal suicidal ideation across 18-months postpartum in mothers with childhood maltreatment histories. J Affect Disord. 2016; 204:138–145. PMID: 27344623.

Article11. MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, Lin E, Boyle MH, Jamieson E, et al. Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2001; 158(11):1878–1883. PMID: 11691695.

Article12. Thompson MP, Kingree JB, Desai S. Gender differences in long-term health consequences of physical abuse of children: data from a nationally representative survey. Am J Public Health. 2004; 94(4):599–604. PMID: 15054012.

Article13. Ammerman BA, Serang S, Jacobucci R, Burke TA, Alloy LB, McCloskey MS. Exploratory analysis of mediators of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and suicidal behavior. J Adolesc. 2018; 69:103–112. PMID: 30286328.

Article14. Martin G, Bergen HA, Richardson AS, Roeger L, Allison S. Sexual abuse and suicidality: gender differences in a large community sample of adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2004; 28(5):491–503. PMID: 15159067.

Article15. Wang YY, Jiang NZ, Cheung EF, Sun HW, Chan RC. Role of depression severity and impulsivity in the relationship between hopelessness and suicidal ideation in patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015; 183:83–89. PMID: 26001667.

Article16. Keilp JG, Ellis SP, Gorlyn M, Burke AK, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ, et al. Suicidal ideation declines with improvement in the subjective symptoms of major depression. J Affect Disord. 2018; 227:65–70. PMID: 29053977.

Article17. Handley TE, Hiles SA, Inder KJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Kelly BJ, Lewin TJ, et al. Predictors of suicidal ideation in older people: a decision tree analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014; 22(11):1325–1335. PMID: 24012228.

Article18. Park CH, Lee JW, Lee SY, Moon JJ, Jeon DW, Shim SH, et al. The Korean Cohort for the Model Predicting a Suicide and Suicide-related Behavior: study rationale, methodology, and baseline sample characteristics of a long-term, large-scale, multi-center, prospective, naturalistic, observational cohort study. Compr Psychiatry. 2019; 88:29–38. PMID: 30468986.

Article19. Bremner JD, Bolus R, Mayer EA. Psychometric properties of the early trauma inventory–self report. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007; 195(3):211–218. PMID: 17468680.

Article20. Lee US, Shin HC, Yang YJ, Cho JJ, An GYR, Kim SH, et al. Development of the stress questionnaire for KNHANES. Updated 2010. Accessed September 25, 2020. http://www.ndsl.kr/ndsl/commons/util/ndslOriginalView.do?dbt=TRKO&cn=TRKO201300000362&rn=&url=&pageCode=PG18.21. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(9):606–613. PMID: 11556941.22. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988; 56(6):893–897. PMID: 3204199.

Article23. Wu Y, Wen ZL. Item parceling strategies in structural equation modeling. Xin Li Ke Xue Jin Zhan. 2011; 19(12):1859–1867.24. Osman A, Kopper BA, Barrios FX, Osman JR, Wade T. The Beck Anxiety Inventory: reexamination of factor structure and psychometric properties. J Clin Psychol. 1997; 53(1):7–14. PMID: 9120035.

Article25. Jang HA, Park EH, Jon DI, Park HJ, Hong HJ, Jung MH, et al. Validation of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale in depression patients. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2014; 33(4):799–814.26. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011; 168(12):1266–1277. PMID: 22193671.

Article27. DiIorio CK. Measurement in Health Behavior: Methods for Research and Evaluation. San Francisco, CA: A Wiley Imprint;2006.28. Taber KS. The use of Cronbach's alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ. 2018; 48(6):1273–1296.

Article29. Jeon JR, Lee EH, Lee SW, Jeong EG, Kim JH, Lee D, et al. The early trauma inventory self report-short form: psychometric properties of the Korean version. Psychiatry Investig. 2012; 9(3):229–235.

Article30. Yook S, Kim Z. A clinical study on the Korean version of Beck Anxiety Inventory: comparative study of patient and non-patient. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1997; 16(1):185–197.31. An J, Seo E, Lim K, Shin J, Kim J. Standardization of the Korean version of screening tool for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ-9). J Korean Soc Biol Ther Psychiatry. 2013; 19(1):47–56.32. Kamath P, Reddy YC, Kandavel T. Suicidal behavior in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007; 68(11):1741–1750. PMID: 18052568.

Article33. Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005; 1(1):293–319. PMID: 17716090.

Article34. Finlay-Jones R, Brown GW. Types of stressful life event and the onset of anxiety and depressive disorders. Psychol Med. 1981; 11(4):803–815. PMID: 7323236.

Article35. Revollo HW, Qureshi A, Collazos F, Valero S, Casas M. Acculturative stress as a risk factor of depression and anxiety in the Latin American immigrant population. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2011; 23(1):84–92. PMID: 21338303.

Article36. de Cunha ACB, Akerman LFP, Rocha AC, de Castro Rezende KB, Amim J, Bornia RG. Stress and anxiety in pregnant women from a screening program for maternal-fetal risks. J Gynecol Obstet. 2017; 1(2):013.37. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association;2000.38. Chellappa SL, Araújo JF. Sleep disorders and suicidal ideation in patients with depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2007; 153(2):131–136. PMID: 17658614.

Article39. Lindh ÅU, Waern M, Beckman K, Renberg ES, Dahlin M, Runeson B. Short term risk of non-fatal and fatal suicidal behaviours: the predictive validity of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale in a Swedish adult psychiatric population with a recent episode of self-harm. BMC Psychiatry. 2018; 18(1):319. PMID: 30285661.

Article40. Conway PM, Erlangsen A, Teasdale TW, Jakobsen IS, Larsen KJ. Predictive validity of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale for short-term suicidal behavior: a Danish study of adolescents at a high risk of suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2017; 21(3):455–469. PMID: 27602917.

Article41. Zisk A, Abbott CH, Ewing SK, Diamond GS, Kobak R. The Suicide Narrative Interview: adolescents' attachment expectancies and symptom severity in a clinical sample. Attach Hum Dev. 2017; 19(5):447–462. PMID: 28002988.

Article42. Hiramura H, Shono M, Tanaka N, Nagata T, Kitamura T. Prospective study on suicidal ideation among Japanese undergraduate students: correlation with stressful life events, depression, and depressogenic cognitive patterns. Arch Suicide Res. 2008; 12(3):238–250. PMID: 18576205.

Article43. Anastasiades MH, Kapoor S, Wootten J, Lamis DA. Perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation in undergraduate women with varying levels of mindfulness. Arch Women Ment Health. 2017; 20(1):129–138.

Article44. Kim G, Cha S. A predictive model of suicidal ideation in Korean college students. Public Health Nurs. 2018; 35(6):490–498. PMID: 30117190.

Article45. Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM. Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1999; 156(2):181–189. PMID: 9989552.46. Schechter M, Ronningstam E, Herbstman B, Goldblatt MJ. Psychotherapy with suicidal patients: The integrative psychodynamic approach of the Boston Suicide Study Group. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019; 55(6):303.

Article47. Shneidman ES. What do suicides have in common? Summary of the psychological approach. In : Bongar BM, editor. Suicide: Guidelines for Assessment, Management, and Treatment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press;1992. p. 3–15.48. Maltsberger JT, Goldblatt MJ, Ronningstam E, Weinberg I, Schechter M. Traumatic subjective experiences invite suicide. J Am Acad Psychoanal Dyn Psychiatry. 2011; 39(4):671–693. PMID: 22168631.

Article49. Little M. On basic unity. Int J Psychoanal. 1991; 72(Pt 2):364. PMID: 1874596.50. Turecki G. The molecular bases of the suicidal brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014; 15(12):802–816. PMID: 25354482.

Article51. Lau JY, Eley TC, Stevenson J. Examining the state-trait anxiety relationship: a behavioural genetic approach. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2006; 34(1):18.

Article52. Spielberger CD. Anxiety and Behavior. New York, NY: Academic Press;2013.53. Bruce LC, Heimberg RG, Blanco C, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Childhood maltreatment and social anxiety disorder: implications for symptom severity and response to pharmacotherapy. Depress Anxiety. 2012; 29(2):132–139.

Article54. Bruce LC, Heimberg RG, Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Childhood maltreatment and response to cognitive behavioral therapy among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2013; 30(7):662–669. PMID: 23554134.

Article55. Naderi S, Naderi S, Delavar A, Dortaj F. The effect of physical exercise on anxiety among the victims of child abuse. Sport Sci Health. 2019; 15(3):519–525.

Article56. Kraepelin E. Psychiatrie. 6th ed. Leipzig: Barth;1899.57. Sani G, Vöhringer PA, Barroilhet SA, Koukopoulos AE, Ghaemi SN. The Koukopoulos Mixed Depression Rating Scale (KMDRS): an International Mood Network (IMN) validation study of a new mixed mood rating scale. J Affect Disord. 2018; 232:9–16. PMID: 29459190.

Article58. Parker G, McCraw S, Blanch B, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Synnott H, Rees AM. Discriminating melancholic and non-melancholic depression by prototypic clinical features. J Affect Disord. 2013; 144(3):199–207. PMID: 22868058.

Article59. Sani G, Tondo L, Koukopoulos A, Reginaldi D, Kotzalidis GD, Koukopoulos AE, et al. Suicide in a large population of former psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011; 65(3):286–295. PMID: 21507136.

Article60. Balázs J, Benazzi F, Rihmer Z, Rihmer A, Akiskal KK, Akiskal HS. The close link between suicide attempts and mixed (bipolar) depression: implications for suicide prevention. J Affect Disord. 2006; 91(2-3):133–138. PMID: 16458364.

Article61. Koukopoulos A, Koukopoulos A. Agitated depression as a mixed state and the problem of melancholia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1999; 22(3):547–564. PMID: 10550855.

Article62. Gelder M, Gath D, Mayou R, Crown P. Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications;1996.63. Day RK. Psychomotor agitation: poorly defined and badly measured. J Affect Disord. 1999; 55(2-3):89–98. PMID: 10628877.

Article64. Hamilton M. Mood disorders: clinical features. In : Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, editors. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 5th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins;1989. p. 892–913.65. Kendell RE, Lawrie SM, Johnstone EC. Diagnosis and classification. In : Kendell RE, Zealley AK, editors. Companion to Psychiatric Studies. 5th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone;1993. p. 277–294.66. Dozois DJ, Dobson KS, Ahnberg JL. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory–II. Psychol Assess. 1998; 10(2):83–89.

Article67. Lee K, Kim D, Cho Y. Exploratory factor analysis of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a psychiatric outpatient population. J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33(16):e128. PMID: 29651821.

Article68. Simon NM, Pollack MH, Ostacher MJ, Zalta AK, Chow CW, Fischmann D, et al. Understanding the link between anxiety symptoms and suicidal ideation and behaviors in outpatients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007; 97(1-3):91–99. PMID: 16820212.

Article69. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Watkins ER. A heuristic for developing transdiagnostic models of psychopathology: explaining multifinality and divergent trajectories. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011; 6(6):589–609. PMID: 26168379.70. Leahy RL. A model of emotional schemas. Cognit Behav Pract. 2002; 9(3):177–190.

Article71. Spasojević J, Alloy LB. Who becomes a depressive ruminator? Developmental antecedents of ruminative response style. J Cogn Psychother. 2002; 16(4):405–419.

Article72. Liu BP, Wang XT, Liu ZZ, Wang ZY, Liu X, Jia CX. Stressful life events, insomnia and suicidality in a large sample of Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2019; 249:404–409. PMID: 30822663.

Article73. Ang RP, Huan VS. Relationship between academic stress and suicidal ideation: testing for depression as a mediator using multiple regression. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2006; 37(2):133–143. PMID: 16858641.

Article74. Buitron V, Hill RM, Pettit JW, Green KL, Hatkevich C, Sharp C. Interpersonal stress and suicidal ideation in adolescence: an indirect association through perceived burdensomeness toward others. J Affect Disord. 2016; 190:143–149. PMID: 26519633.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Effects of Social Anxiety, Self-Esteem, and Depression on Suicidal Ideation in Korean Adolescents

- A Study on Correlation between Anxiety Symptoms and Suicidal Ideation

- The Association among Suicidal Ideation, Anxiety Symptoms, and Quality of Life in Firefighters

- What Kind of Stress Is Associated with Depression, Anxiety and Suicidal Ideation in Korean Employees?

- Factors on the Pathway from Trauma to Suicidal Ideation in Adolescents