Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg.

2021 Feb;25(1):46-53. 10.14701/ahbps.2021.25.1.46.

Patency of Hemashield grafts versus ringed Gore-Tex grafts in middle hepatic vein reconstruction for living donor liver transplantation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Hepatobiliary Surgery and Liver Transplantation, Department of Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2513175

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14701/ahbps.2021.25.1.46

Abstract

- Backgrounds/Aims

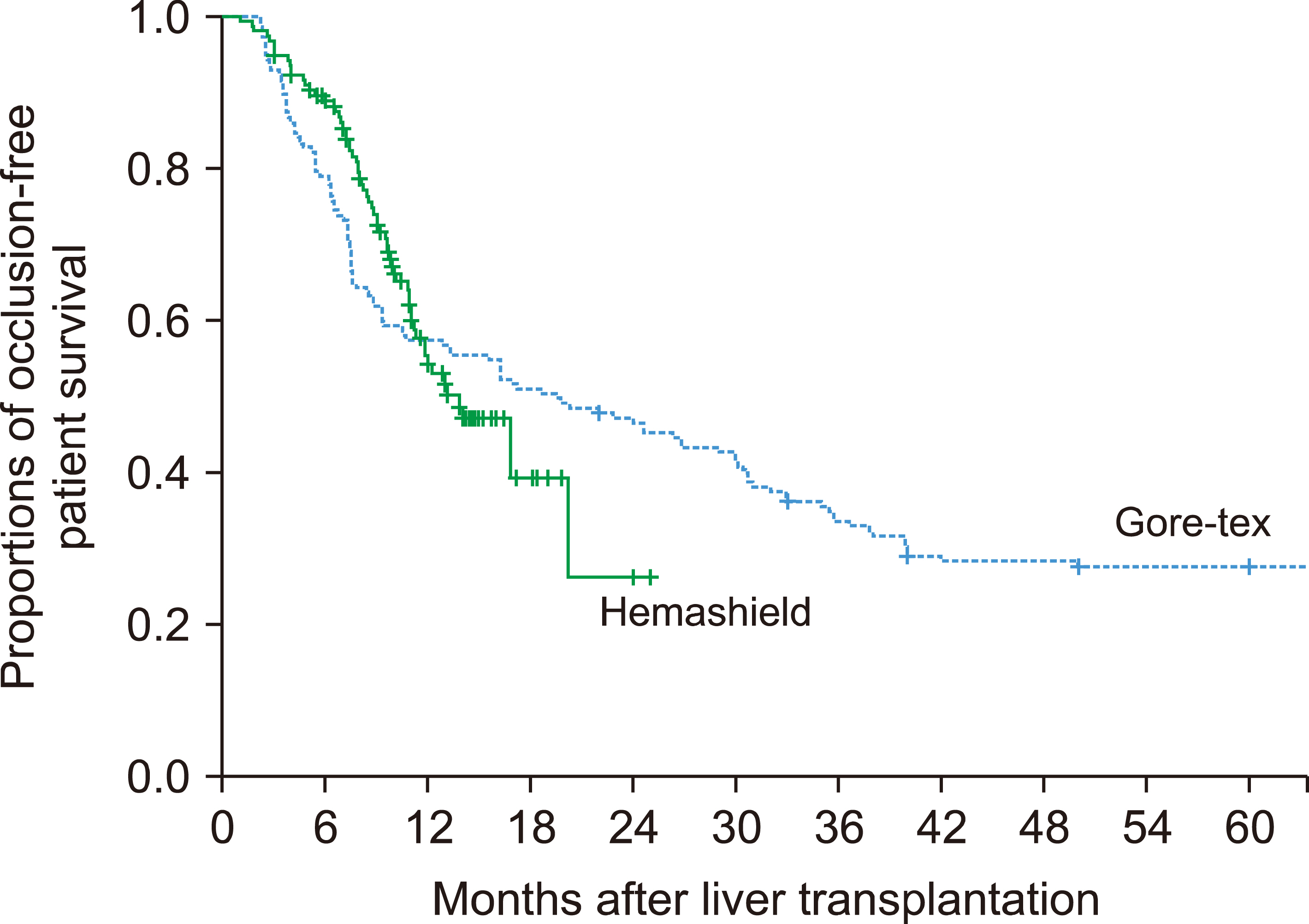

Owing to the short supply of homologous vein allografts, we previously used ringed Gore-Tex vascular grafts for middle hepatic vein (MHV) reconstruction in living donor liver transplantation. When ringed Gore-Tex grafts became unavailable, we used Hemashield vascular grafts. This study aimed to compare the patency and complication rates of Hemashield and ringed Gore-Tex grafts.

Methods

This retrospective two-arm study compared the study group that received Hemashield grafts (n=157) and the propensity score-matched control group that received ringed Gore-Tex grafts (n=157).

Results

In the Hemashield and Gore-Tex groups, the recipient age was 54.7±9.4 and 53.3±6.3 years; Model for End-stage Liver Disease scores were 15.9±9.2 and 16.9±8.3; and graft-recipient weight ratios were 1.07±0.24 and 1.10±0.23, respectively. In the Hemashield group, V5 reconstruction was performed using single (n=113, 72.0%), double (n=39, 24.8%), and triple (n=3, 1.9%) anastomoses. The proportion of double and triple anastomoses for V5 and V8 was higher in the Hemashield group than in the Gore-Tex group. Two (1.3%) patients required MHV conduit stenting owing to early thrombosis of the Hemashield graft. There was no difference in conduit occlusion-free patient survival rates between groups (p=0.91). The incidence of accidental conduit migration in the Hemashield and Gore-Tex groups was 0 (0%) and 2 (1.3%), respectively.

Conclusions

Hemashield grafts used in MHV reconstruction demonstrated acceptably high short- and mid-term patency rates, no incidences of conduit migration, easy handling, and good flexibility for length adjustment. Therefore, we suggest that the Hemashield graft is the preferentially suitable prosthetic material for MHV reconstruction.

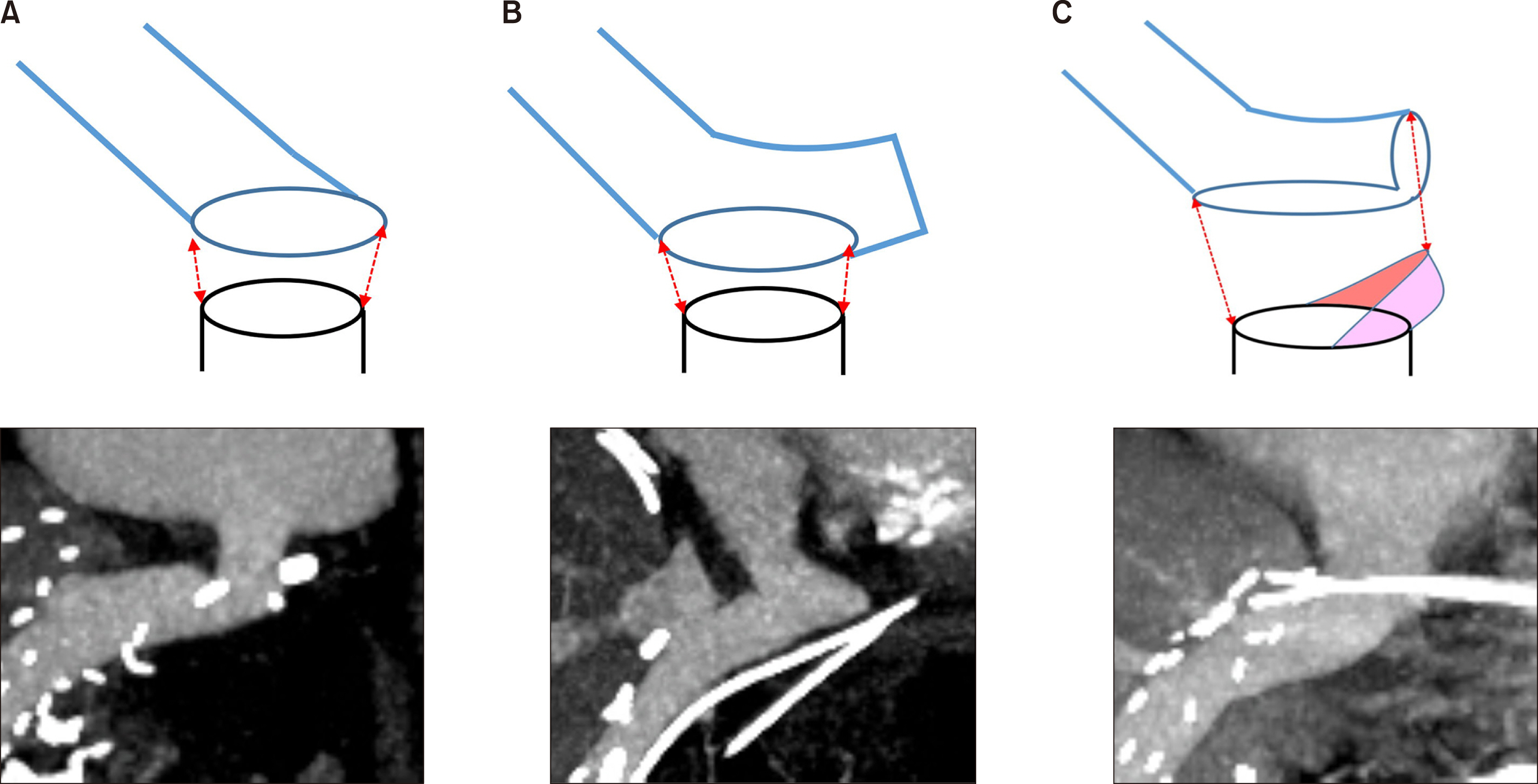

Figure

Reference

-

1. Hwang S, Lee SG, Lee YJ, Sung KB, Park KM, Kim KH, et al. 2006; Lessons learned from 1,000 living donor liver transplantations in a single center: how to make living donations safe. Liver Transpl. 12:920–927. DOI: 10.1002/lt.20734. PMID: 16721780.

Article2. Hwang S, Lee SG, Ahn CS, Park KM, Kim KH, Moon DB, et al. 2005; Cryopreserved iliac artery is indispensable interposition graft material for middle hepatic vein reconstruction of right liver grafts. Liver Transpl. 11:644–649. DOI: 10.1002/lt.20430. PMID: 15915499.

Article3. Sugawara Y, Makuuchi M, Akamatsu N, Kishi Y, Niiya T, Kaneko J, et al. 2004; Refinement of venous reconstruction using cryopreserved veins in right liver grafts. Liver Transpl. 10:541–547. DOI: 10.1002/lt.20129. PMID: 15048798.

Article4. Hwang S, Lee SG, Song GW, Lee HJ, Park JI, Ryu JH. 2007; Use of endarterectomized atherosclerotic artery allograft for hepatic vein reconstruction of living donor right lobe graft. Liver Transpl. 13:306–308. DOI: 10.1002/lt.21045. PMID: 17256786.

Article5. Hwang S, Jung DH, Ha TY, Ahn CS, Moon DB, Kim KH, et al. 2012; Usability of ringed polytetrafluoroethylene grafts for middle hepatic vein reconstruction during living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 18:955–965. DOI: 10.1002/lt.23456. PMID: 22511404.

Article6. Park GC, Hwang S, Ha TY, Song GW, Jung DH, Ahn CS, et al. 2019; Hemashield vascular graft is a preferable prosthetic graft for middle hepatic vein reconstruction in living donor liver transplantation. Ann Transplant. 24:639–646. DOI: 10.12659/AOT.919780. PMID: 31844037. PMCID: PMC6936210.

Article7. Jeong IJ, Hwang S, Ha TY, Song GW, Jung DH, Park GC, et al. 2020; Technical refinement of prosthetic vascular graft anastomosis to recipient inferior vena cava for secure middle hepatic vein reconstruction in living donor liver transplantation. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 24:144–149. DOI: 10.14701/ahbps.2020.24.2.144. PMID: 32457258. PMCID: PMC7271118.

Article8. Ko GY, Sung KB, Yoon HK, Kim JH, Song HY, Seo TS, et al. 2002; Endovascular treatment of hepatic venous outflow obstruction after living-donor liver transplantation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 13:591–599. DOI: 10.1016/S1051-0443(07)61652-2. PMID: 12050299.

Article9. Ko GY, Sung KB, Yoon HK, Kim KR, Kim JH, Gwon DI, et al. 2008; Early posttransplant hepatic venous outflow obstruction: long-term efficacy of primary stent placement. Liver Transpl. 14:1505–1511. DOI: 10.1002/lt.21560. PMID: 18825710.

Article10. Ha TY, Hwang S, Jung DH, Ahn CS, Kim KH, Moon DB, et al. 2014; Complications analysis of polytetrafluoroethylene grafts used for middle hepatic vein reconstruction in living-donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 46:845–849. DOI: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.10.054. PMID: 24767363.

Article11. Papanicolaou G, Beach KW, Zierler RE, Detmer PR, Strandness DE Jr. 1995; Hemodynamics of stenotic infrainguinal vein grafts: theoretic considerations. Ann Vasc Surg. 9:163–171. DOI: 10.1007/BF02139659. PMID: 7786702.

Article12. Hsu SC, Thorat A, Yang HR, Poon KS, Li PC, Yeh CC, et al. 2017; Assessing the safety of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene synthetic grafts in living donor liver transplantation: graft migration into hollow viscous organs- diagnosis and treatment options. Med Sci Monit. 23:3284–3292. DOI: 10.12659/MSM.902636. PMID: 28683053. PMCID: PMC5510995.13. Sultan AM, Shehta A, Salah T, Elshoubary M, Wahab MA. 2018; Spontaneous migration of thrombosed synthetic vascular graft to the duodenum after living-donor liver transplantation: a case- report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 45:42–44. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.03.013. PMID: 29571064. PMCID: PMC6000742.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Patency of middle hepatic vein reconstruction using Hemashield grafts compared with ringed polytetrafluoroethylene grafts in living donor liver transplantation

- Human dermis as a new substitute for middle hepatic vein during living donor liver transplantation: early results from ongoing clinical trial

- A critical complication of the interposition grafts using a cryopreserved aortic allograft for middle hepatic vein reconstruction in living donor liver transplantation

- Asymptomatic migration of hemashield vascular graft used for middle hepatic vein reconstruction of living donor liver transplantation

- Tailored techniques of graft outflow vein reconstruction in pediatric liver transplantation at Asan Medical Center