J Korean Med Sci.

2020 Nov;35(44):e365. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e365.

Life Expectancy in Areas around Subway Stations in the Seoul Metropolitan Area in Korea, 2008–2017

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Health Policy and Management, Jeju National University School of Medicine, Jeju, Korea

- 2Department of Health Policy and Management, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Institue of Health Policy and Management, Seoul National University Medical Research Center, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2508766

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e365

Abstract

- Background

This study aimed to calculate life expectancy in the areas around 614 subway stations on 23 subway lines in the Seoul metropolitan area of Korea from 2008 to 2017.

Methods

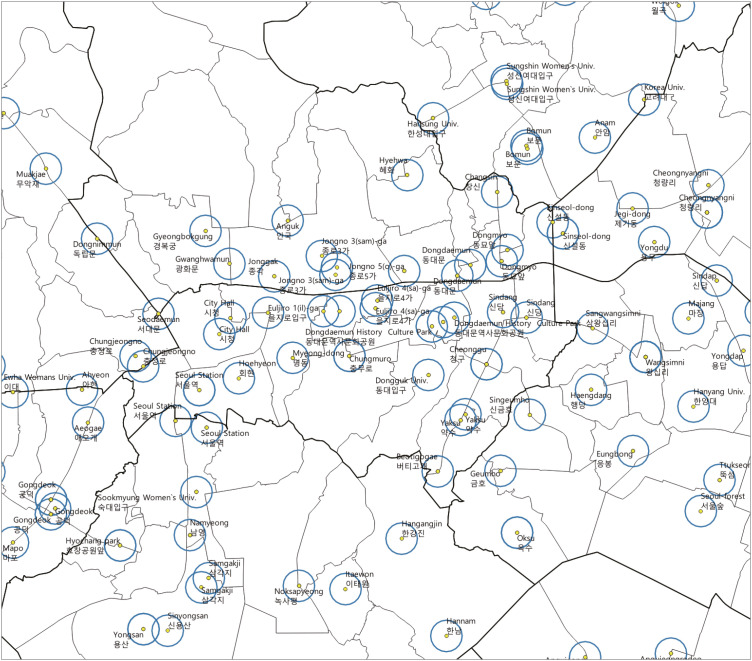

We used the National Health Information Database provided by the National Health Insurance Service, which covers the whole population of Korea. The analysis was conducted on the level of the smallest administrative units within a 200-m radius of each subway station. Life expectancy was calculated by constructing an abridged life table using the number of population and deaths in each area and 5-year age groups (0, 1–4, …, 85+) during the whole study period.

Results

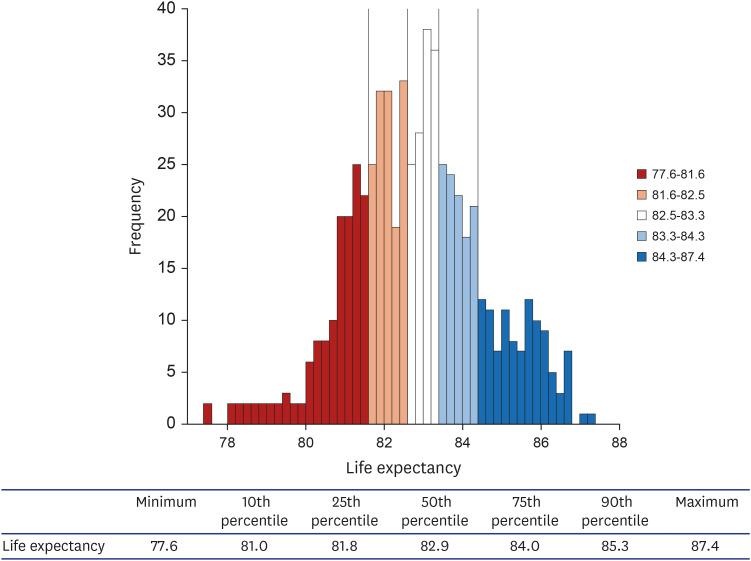

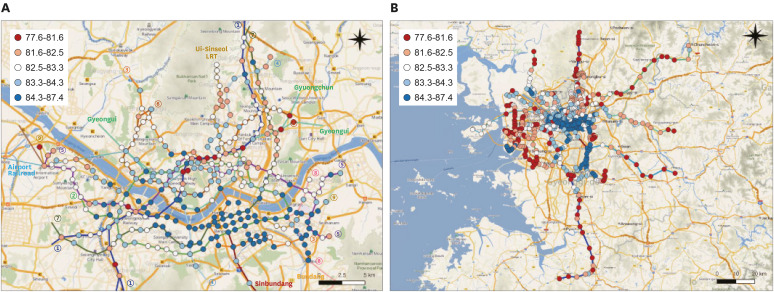

The median life expectancy in the areas around 614 subway stations was 82.9 years (interquartile range, 2.2 years; minimum, 77.6 years; maximum, 87.4 years). The life expectancy of areas around subway stations located in Seoul was higher than those in Incheon and Gyeonggi-do, but variation within the region was observed. Significant differences were observed between some adjacent subway stations. In Incheon and Gyeonggi-do, substantially higher life expectancy was found around subway stations in newly developed urban areas, and lower life expectancy was found in central Incheon and suburbs in Gyeonggi-do.

Conclusion

When using areas around subway stations as the unit of analysis, variation in life expectancy in the Seoul metropolitan area was observed. This approach may reduce the stigma associated with presenting health inequalities at the level of the smallest administrative units and foster public awareness of health inequalities.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Cancer-free Life Expectancy in Small Administrative Areas in Korea and Its Associations with Regional Health Insurance Premiums

Eunjeong Noh, Hee-Yeon Kang, Jinwook Bahk, Ikhan Kim, Young-Ho Khang

J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(42):e269. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e269.

Reference

-

1. Dwyer-Lindgren L, Cork MA, Sligar A, Steuben KM, Wilson KF, Provost NR, et al. Mapping HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2017. Nature. 2019; 570(7760):189–193. PMID: 31092927.

Article2. Reiner RC, Welgan CA, Casey DC, Troeger CE, Baumann MM, Nguyen QP, et al. Identifying residual hotspots and mapping lower respiratory infection morbidity and mortality in African children from 2000 to 2017. Nat Microbiol. 2019; 4(12):2310–2318. PMID: 31570869.

Article3. Burstein R, Henry NJ, Collison ML, Marczak LB, Sligar A, Watson S, et al. Mapping 123 million neonatal, infant and child deaths between 2000 and 2017. Nature. 2019; 574(7778):353–358. PMID: 31619795.4. Local Burden of Disease Child Growth Failure Collaborators. Mapping child growth failure across low- and middle-income countries. Nature. 2020; 577(7789):231–234. PMID: 31915393.5. Dwyer-Lindgren L, Stubbs RW, Bertozzi-Villa A, Morozoff C, Callender C, Finegold SB, et al. Variation in life expectancy and mortality by cause among neighbourhoods in King County, WA, USA, 1990–2014: a census tract-level analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Public Health. 2017; 2(9):e400–10. PMID: 29253411.

Article6. Talbot TO, Done DH, Babcock GD. Calculating census tract-based life expectancy in New York state: a generalizable approach. Popul Health Metr. 2018; 16(1):1. PMID: 29373976.

Article7. Asaria P, Fortunato L, Fecht D, Tzoulaki I, Abellan JJ, Hambly P, et al. Trends and inequalities in cardiovascular disease mortality across 7932 English electoral wards, 1982–2006: Bayesian spatial analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012; 41(6):1737–1749. PMID: 23129720.

Article8. Congdon P. Modelling changes in small area disability free life expectancy: trends in London wards between 2001 and 2011. Stat Med. 2014; 33(29):5138–5150. PMID: 25196376.

Article9. Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010. Fair society, healthier lives: the Marmot review. Updated 2010. Accessed March 24, 2020. http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review.10. Stephens AS, Purdie S, Yang B, Moore H. Life expectancy estimation in small administrative areas with non-uniform population sizes: application to Australian New South Wales local government areas. BMJ Open. 2013; 3(12):e003710.

Article11. Jonker MF, Congdon PD, van Lenthe FJ, Donkers B, Burdorf A, Mackenbach JP. Small-area health comparisons using health-adjusted life expectancies: a Bayesian random-effects approach. Health Place. 2013; 23:70–78. PMID: 23778148.

Article12. Ngamini Ngui A, Apparicio P, Moltchanova E, Vasiliadis HM. Spatial analysis of suicide mortality in Québec: spatial clustering and area factor correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2014; 220(1-2):20–30. PMID: 25095757.

Article13. Kim I, Lim HK, Kang HY, Khang YH. Comparison of three small-area mortality metrics according to urbanity in Korea: the standardized mortality ratio, comparative mortality figure, and life expectancy. Popul Health Metrics. 2020; 18:3.

Article14. Kim JH, Yoon TH. Comparisons of health inequalities in small areas with using the standardized mortality ratios in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2008; 41(5):300–306. PMID: 18827497.

Article15. Yoon TH, Noh M, Han J, Jung-Choi K, Khang YH. Deprivation and suicide mortality across 424 neighborhoods in Seoul, South Korea: a Bayesian spatial analysis. Int J Public Health. 2015; 60(8):969–976. PMID: 26022192.

Article16. Cheshire J. Featured graphic. Lives on the line: mapping life expectancy along the London Tube network. Environ Plann A. 2012; 44(7):1525–1528.17. Marmot M. The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World. Oxford, UK: Bloomsbury Press;2015. p. 27–28.18. Seong SC, Kim YY, Khang YH, Park HJ, Kang HJ, Lee H, et al. Data resource profile: the National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46(3):799–800. PMID: 27794523.19. Preston S, Heuveline P, Guillot M. Demography: Measuring and Modeling Population Processes. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell;2000.20. Eayres D, Williams ES. Evaluation of methodologies for small area life expectancy estimation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004; 58(3):243–249. PMID: 14966240.

Article21. Office for National Statistics. Life Expectancy at Birth: Methodological Options for Small Populations. Norwich, UK: Office for National Statistics;2003.22. Silcocks PB, Jenner DA, Reza R. Life expectancy as a summary of mortality in a population: statistical considerations and suitability for use by health authorities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001; 55(1):38–43. PMID: 11112949.

Article23. Andreev EM, Shkolnikov VM. Spreadsheet for Calculation of Confidence Limits for Any Life Table or Health-Life Table Quantity. Rostock, Germany: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research;2010.24. UN-HABITAT/WHO. Hidden Cities: Unmasking and Overcoming Health Inequities in Urban Settings. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2010.25. Galea S, Freudenberg N, Vlahov D. Cities and population health. Soc Sci Med. 2005; 60(5):1017–1033. PMID: 15589671.

Article26. Shin H, Lee S, Chu JM. Development of composite deprivation index for Korea: the correlation with standardized mortality ratio. J Prev Med Public Health. 2009; 42(6):392–402. PMID: 20009486.

Article27. Pearce J. The ‘blemish of place’: stigma, geography and health inequalities. A commentary on Tabuchi, Fukuhara & Iso. Soc Sci Med. 2012; 75(11):1921–1924. PMID: 22917749.28. Veugelers PJ, Kim AL, Guernsey JR. Inequalities in health. Analytic approaches based on life expectancy and suitable for small area comparisons. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000; 54(5):375–380. PMID: 10814659.

Article29. Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Soc Sci Med. 2002; 55(1):125–139. PMID: 12137182.

Article30. Northridge ME, Sclar ED, Biswas P. Sorting out the connections between the built environment and health: a conceptual framework for navigating pathways and planning healthy cities. J Urban Health. 2003; 80(4):556–568. PMID: 14709705.

Article31. Friel S, Akerman M, Hancock T, Kumaresan J, Marmot M, Melin T, et al. Addressing the social and environmental determinants of urban health equity: evidence for action and a research agenda. J Urban Health. 2011; 88(5):860–874. PMID: 21877255.

Article32. Smith N. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. Paju, Korea: Dongnyok;2019.33. Choi EY. The differentiation of reproductions of educational capitals and the formation of the gated city. J Korean Geogr Soc. 2004; 39(3):374–390.34. Choi E. The formation of rigid cycle of the rich in Gangnam - according to the change of condo prices (1989–2004). J Korean Urban Geogr Soc. 2006; 9(1):33–45.35. Park BG, Jang JB. Gangnam-ization and Korean urban ideology. J Korean Assoc Reg Geogr. 2016; 22(2):287–306.36. Kim CS, Yun SC, Kim HR, Khang YH. A multilevel study on the relationship between the residential distribution of high class (power elites) and smoking in Seoul. J Prev Med Public Health. 2006; 39(1):30–38. PMID: 16613069.37. Kim I, Bahk J, Yoon TH, Yun SC, Khang YH. Income differences in smoking prevalences in 245 districts of South Korea: patterns by area deprivation and urbanity, 2008–2014. J Prev Med Public Health. 2017; 50(2):100–126. PMID: 28372354.

Article38. Jung-Choi K, Khang YH, Cho HJ. Socioeconomic differentials in cause-specific mortality among 1.4 million South Korean public servants and their dependents. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011; 65(7):632–638. PMID: 20584732.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Distribution of Airborne Fungi, Particulate Matter and Carbon Dioxide in Seoul Metropolitan Subway Stations

- A Clinical Analysis of Trauma Pattern in Subway Station

- Cancer-free Life Expectancy in Small Administrative Areas in Korea and Its Associations with Regional Health Insurance Premiums

- Life Expectancy and Inequalities Therein by Income From 2016 to 2018 Across the 253 Electoral Constituencies of the National Assembly of the Korea

- Factors Affecting Subjective Life Expectancy: Analysis of Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging