Clinical management for small bowel of Crohn’s disease in the treat-to-target era: now is the time to optimize treatment based on the dominant lesion

- Affiliations

-

- 1Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Division of Internal Medicine, Hyogo College of Medicine, Nishinomiya, Japan

- KMID: 2508560

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2020.00032

Abstract

- A treat-to-target strategy, in which treatment is continuously adjusted according to the results of scheduled objective monitoring, is optimal for patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) in the era of biologics. The small bowel is a common site of intractable CD, which may result from multiple strictures or expanding lesions. To improve the prognosis of patients with small bowel CD, lesions should be proactively monitored within the subclinical phase. Objective assessment of small bowel lesions is technically difficult, however, due to the relatively poor correlation between endoscopic activity and clinical symptoms or biomarker titers. The presence of proximal small bowel lesions and asymptomatic “Real Silent CD” must be considered. Endoscopy remains the gold standard to assess these lesions. In clinical practice, the advantages and disadvantages of each imaging modality and biomarker must be carefully weighed for appropriate application and reliable monitoring. The prevalence of small bowel lesions depends on the precision of the imaging modality used for detection. Clinical management should be based on the dominant location of the intestinal lesions rather than classical classification. Optimal strategies for detecting and treating small bowel lesions in patients with CD must be developed utilizing reliable, precise, and objective monitoring.

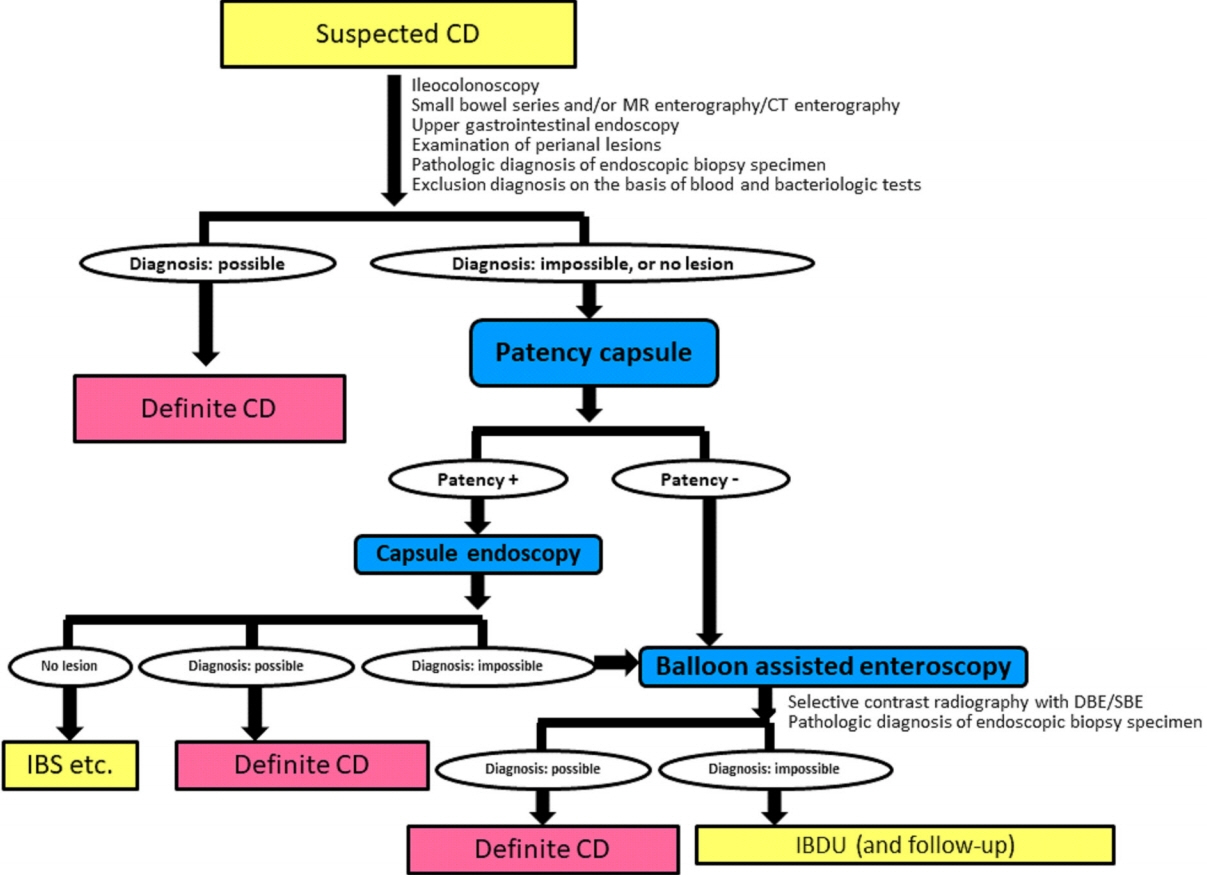

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

Fecal S100A12 is associated with future hospitalization and step-up of medical treatment in patients with Crohn’s disease in clinical remission: a pilot study

Sun-Ho Lee, Sung Wook Hwang, Sang Hyoung Park, Dong-Hoon Yang, Jeong-Sik Byeon, Seung-Jae Myung, Suk-Kyun Yang, Byong Duk Ye

Intest Res. 2022;20(2):203-212. doi: 10.5217/ir.2021.00020.Intestinal ultrasonography and fecal calprotectin for monitoring inflammation of ileal Crohn’s disease: two complementary tests

José María Paredes, Tomás Ripollés, Ángela Algarra, Rafael Diaz, Nadia Moreno, Patricia Latorre, María Jesús Martínez, Pilar Llopis, Antonio López, Eduardo Moreno-Osset

Intest Res. 2022;20(3):361-369. doi: 10.5217/ir.2021.00126.Compositional changes in fecal microbiota associated with clinical phenotypes and prognosis in Korean patients with inflammatory bowel disease

Seung Yong Shin, Young Kim, Won-Seok Kim, Jung Min Moon, Kang-Moon Lee, Sung-Ae Jung, Hyesook Park, Eun Young Huh, Byung Chang Kim, Soo Chan Lee, Chang Hwan Choi

Intest Res. 2023;21(1):148-160. doi: 10.5217/ir.2021.00168.

Reference

-

1. Murakami Y, Nishiwaki Y, Oba MS, et al. Estimated prevalence of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in Japan in 2014: an analysis of a nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2019; 54:1070–1077.

Article2. Ng WK, Wong SH, Ng SC. Changing epidemiological trends of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Intest Res. 2016; 14:111–119.

Article3. Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H, et al. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat Genet. 2015; 47:979–986.

Article4. Watanabe K, Motoya S, Ogata H, et al. Effects of vedolizumab in Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial with exploratory analyses. J Gastroenterol. 2020; 55:291–306.

Article5. Miyazaki T, Watanabe K, Kojima K, et al. Efficacies and related issues of ustekinumab in Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease: a preliminary study. Digestion. 2020; 101:53–59.

Article6. Morita Y, Imai T, Bamba S, et al. Clinical relevance of innovative immunoassays for serum ustekinumab and anti-ustekinumab antibody levels in Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; 35:1163–1170.

Article7. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, et al. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015; 110:1324–1338.8. Colombel JF, Panaccione R, Bossuyt P, et al. Effect of tight control management on Crohn’s disease (CALM): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018; 390:2779–2789.

Article9. Yamamoto H, Ogata H, Matsumoto T, et al. Clinical practice guideline for enteroscopy. Dig Endosc. 2017; 29:519–546.

Article10. de Barros KSC, Flores C, Harlacher L, Francesconi CFM. Evolution of clinical behavior in Crohn’s disease: factors associated with complicated disease and surgery. Dig Dis Sci. 2017; 62:2481–2488.

Article11. Guizzetti L, Zou G, Khanna R, et al. Development of clinical prediction models for surgery and complications in Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2018; 12:167–177.

Article12. Watanabe K, Hosomi S, Noguchi A, et al. Significances and issues for capsule endoscopy in patients with Crohn’s diseasetoward the appropriate use. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2015; 112:1259–1269.13. Click B, Vargas EJ, Anderson AM, et al. Silent Crohn’s disease: asymptomatic patients with elevated C-reactive protein are at risk for subsequent hospitalization. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015; 21:2254–2261.14. Pariente B, Cosnes J, Danese S, et al. Development of the Crohn’s disease digestive damage score, the Lémann score. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011; 17:1415–1422.

Article15. Bhattacharya A, Rao BB, Koutroubakis IE, et al. Silent Crohn’s disease predicts increased bowel damage during multiyear follow-up: the consequences of under-reporting active inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016; 22:2665–2671.

Article16. Yang DH, Yang SK, Park SH, et al. Usefulness of C-reactive protein as a disease activity marker in Crohn’s disease according to the location of disease. Gut Liver. 2015; 9:80–86.

Article17. Verdejo C, Hervías D, Roncero Ó, et al. Fecal calprotectin is not superior to serum C-reactive protein or the Harvey-Bradshaw index in predicting postoperative endoscopic recurrence in Crohn’s disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018; 30:1521–1527.

Article18. Nakamura S, Imaeda H, Nishikawa H, et al. Usefulness of fecal calprotectin by monoclonal antibody testing in adult Japanese with inflammatory bowel diseases: a prospective multicenter study. Intest Res. 2018; 16:554–562.

Article19. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Panés J, Sandborn WJ, et al. Defining disease severity in inflammatory bowel diseases: current and future directions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016; 14:348–354.

Article20. Dionisio PM, Gurudu SR, Leighton JA, et al. Capsule endoscopy has a significantly higher diagnostic yield in patients with suspected and established small-bowel Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010; 105:1240–1248.

Article21. Enns RA, Hookey L, Armstrong D, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the use of video capsule endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2017; 152:497–514.22. Kucharzik T, Wittig BM, Helwig U, et al. Use of intestinal ultrasound to monitor Crohn’s disease activity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017; 15:535–542.

Article23. Aloi M, Di Nardo G, Romano G, et al. Magnetic resonance enterography, small-intestine contrast US, and capsule endoscopy to evaluate the small bowel in pediatric Crohn’s disease: a prospective, blinded, comparison study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015; 81:420–427.

Article24. Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019; 68(Suppl 3):s1–s106.

Article25. Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019; 13:144–164.

Article26. González-Suárez B, Rodriguez S, Ricart E, et al. Comparison of capsule endoscopy and magnetic resonance enterography for the assessment of small bowel lesions in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018; 24:775–780.27. Takenaka K, Ohtsuka K, Kitazume Y, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance and balloon enteroscopic examination of the small intestine in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2014; 147:334–342.

Article28. Solem CA, Loftus EV Jr, Fletcher JG, et al. Small-bowel imaging in Crohn’s disease: a prospective, blinded, 4-way comparison trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 68:255–266.

Article29. Torres J, Burisch J, Riddle M, Dubinsky M, Colombel JF. Preclinical disease and preventive strategies in IBD: perspectives, challenges and opportunities. Gut. 2016; 65:1061–1069.

Article30. Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Beyls J, Kerremans R, Hiele M. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1990; 99:956–963.

Article31. Bouguen G, Levesque BG, Pola S, Evans E, Sandborn WJ. Endoscopic assessment and treating to target increase the likelihood of mucosal healing in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 12:978–985.

Article32. Oshitani N, Yukawa T, Yamagami H, et al. Evaluation of deep small bowel involvement by double-balloon enteroscopy in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006; 101:1484–1489.

Article33. Esaki M, Matsumoto T, Watanabe K, et al. Use of capsule endoscopy in patients with Crohn’s disease in Japan: a multicenter survey. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 29:96–101.

Article34. Watanabe K, Ohmiya N, Nakamura M, Fujiwara Y. A prospective study evaluating the clinical utility of the tag-less patency capsule with extended time for confirming functional patency. Digestion. [published online ahead of print September 19, 2019]. https://doi.org/10.1159/000503027.

Article35. Tokuhara D, Watanabe K, Okano Y, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy in pediatric patients: the first series from Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010; 45:683–691.

Article36. Morimoto K, Watanabe K, Noguchi A, et al. Clinical impact of ultrathin colonoscopy for Crohn’s disease patients with strictures. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 30–Suppl 1:66-70.

Article37. Bewtra M, Fairchild AO, Gilroy E, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease patients’ willingness to accept medication risk to avoid future disease relapse. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015; 110:1675–1681.

Article38. Beppu T, Ono Y, Matsui T, et al. Mucosal healing of ileal lesions is associated with long-term clinical remission after infliximab maintenance treatment in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dig Endosc. 2015; 27:73–81.

Article39. Takenaka K, Fujii T, Suzuki K, et al. Small bowel healing detected by endoscopy in patients with crohn’s disease after treatment with antibodies against tumor necrosis factor. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; 18:1545–1552.

Article40. Danese S, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, et al. Endoscopic, radiologic, and histologic healing with vedolizumab in patients with active Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2019; 157:1007–1018.

Article41. Habtezion A, Nguyen LP, Hadeiba H, Butcher EC. Leukocyte trafficking to the small intestine and colon. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150:340–354.

Article42. Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005; 19 Suppl A:5A–36A.

Article43. Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006; 55:749–753.

Article44. Hall B, Holleran G, McNamara D. Small bowel Crohn’s disease: an emerging disease phenotype? Dig Dis. 2015; 33:42–51.

Article45. Cotter J, Dias de Castro F, Moreira MJ, Rosa B. Tailoring Crohn’s disease treatment: the impact of small bowel capsule endoscopy. J Crohns Colitis. 2014; 8:1610–1615.

Article46. Papay P, Ignjatovic A, Karmiris K, et al. Optimising monitoring in the management of Crohn’s disease: a physician’s perspective. J Crohns Colitis. 2013; 7:653–669.

Article47. Flamant M, Trang C, Maillard O, et al. The prevalence and outcome of jejunal lesions visualized by small bowel capsule endoscopy in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19:1390–1396.

Article48. Dulai PS, Singh S, Vande Casteele N, et al. Should we divide Crohn’s disease into ileum-dominant and isolated colonic diseases? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019; 17:2634–2643.

Article49. Hirai F, Andoh A, Ueno F, et al. Efficacy of endoscopic balloon dilation for small bowel strictures in patients with Crohn’s disease: a nationwide, multi-centre, open-label, prospective cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2018; 12:394–401.

Article50. Hirai F, Beppu T, Takatsu N, et al. Long-term outcome of endoscopic balloon dilation for small bowel strictures in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dig Endosc. 2014; 26:545–551.

Article51. Lan N, Stocchi L, Ashburn JH, et al. Outcomes of endoscopic balloon dilation vs surgical resection for primary ileocolic strictures in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018; 16:1260–1267.

Article52. Higashi D, Katsuno H, Kimura H, et al. Current state of and problems related to cancer of the intestinal tract associated with Crohn’s disease in Japan. Anticancer Res. 2016; 36:3761–3766.53. Matsumoto T, Iwao Y, Igarashi M, et al. Endoscopic and chromoendoscopic atlas featuring dysplastic lesions in surveillance colonoscopy for patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008; 14:259–264.

Article54. Sogawa M, Watanabe K, Egashira Y, et al. Precise endoscopic and pathologic features in a Crohn’s disease case with two fistula-associated small bowel adenocarcinomas complicated by an anal canal adenocarcinoma. Intern Med. 2013; 52:445–449.

Article55. Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, et al. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015; 148:1320–1329.

Article56. Watanabe K, Matsumoto T, Hisamatsu T, et al. Clinical and pharmacokinetic factors associated with adalimumab-induced mucosal healing in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018; 16:542–549.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The role of small bowel endoscopy in small bowel Crohn's disease: when and how?

- Current status of endoscopic balloon dilation for Crohn's disease

- Perspectives on Current and Novel Treatments for Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Pharmacologic treatment for inflammatory bowel disease

- The Pharmacotherapy of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Child and Adolescence