Anesth Pain Med.

2020 Oct;15(4):498-504. 10.17085/apm.20041.

Emergency exploratory laparotomy in a COVID-19 patient - A case report -

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, National Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2508414

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.17085/apm.20041

Abstract

- Background

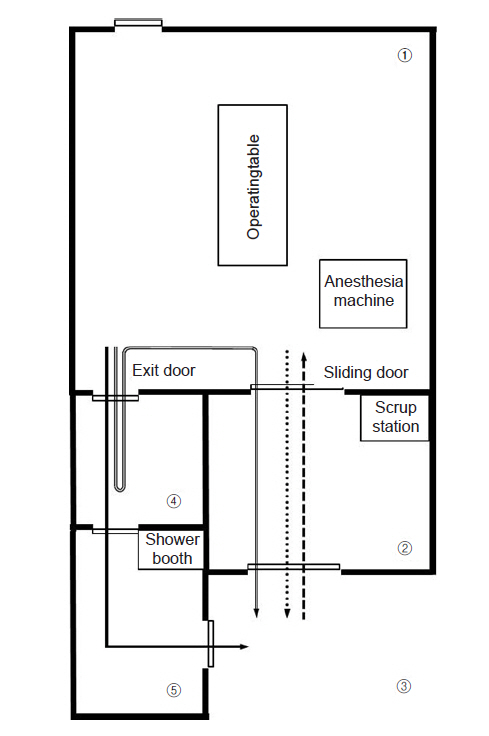

Surgeries in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) put medical staff at a high risk of infection. We report the anesthetic management and infection control of a mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patient who underwent exploratory laparotomy for suspected duodenal ulcer perforation. Case: A 73-year-old man, mechanically ventilated for confirmed COVID-19, showed clinical and radiographic signs of a perforated duodenal ulcer, and he was transferred under sedation and intubation to a negative-pressure operating room. The operating and assistant staff wore personal protective equipment. High-efficiency particulate absorbing (HEPA) filters were inserted into the expiratory circuits of the anesthesia machine and portable ventilator. No participating staff contracted COVID-19, although the patient later died due to pneumonia.

Conclusions

This report can contribute to establishing clinical guidelines for the surgical management and operation room setting of COVID-19 patients.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020; 323:1239–42.2. COVID-19 National Emergency Response Center; Epidemiology and Case Management Team; Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 28 cases of coronavirus disease in South Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020; 11:8–14.3. Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020; 67:568–76.4. Wong J, Goh QY, Tan Z, Lie SA, Tay YC, Ng SY, et al. Preparing for a COVID-19 pandemic: a review of operating room outbreak response measures in a large tertiary hospital in Singapore. Can J Anaesth. 2020; 67:732–45.5. Tompkins BM, Kerchberger JP. Special article: personal protective equipment for care of pandemic influenza patients: a training workshop for the powered air purifying respirator. Anesth Analg. 2010; 111:933–45.6. Søreide K, Thorsen K, Harrison EM, Bingener J, Møller MH, Ohene-Yeboah M, et al. Perforated peptic ulcer. Lancet. 2015; 386:1288–98.7. Ghekiere O, Lesnik A, Hoa D, Laffargue G, Uriot C, Taourel P. Value of computed tomography in the diagnosis of the cause of nontraumatic gastrointestinal tract perforation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007; 31:169–76.8. Kim JY, Song JY, Yoon YK, Choi SH, Song YG, Kim SR, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome infection control and prevention guideline for healthcare facilities. Infect Chemother. 2015; 47:278–302.9. Sehulster L, Chinn RY; CDC; HICPAC. Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities. Recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003; 52:1–42.10. Park J, Yoo SY, Ko JH, Lee SM, Chung YJ, Lee JH, et al. Infection prevention measures for surgical procedures during a Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak in a tertiary care hospital in South Korea. Sci Rep. 2020; 10:325.11. Park MH, Kim HR, Choi DH, Sung JH, Kim JH. Emergency cesarean section in an epidemic of the Middle East respiratory syndrome: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2016; 69:287–91.12. Xia H, Zhao S, Wu Z, Luo H, Zhou C, Chen X. Emergency caesarean delivery in a patient with confirmed COVID-19 under spinal anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2020; 124:e216–8.13. Chen R, Zhang Y, Huang L, Cheng BH, Xia ZY, Meng QT. Safety and efficacy of different anesthetic regimens for parturients with COVID-19 undergoing cesarean delivery: a case series of 17 patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020; 67:655–63.14. Liew MF, Siow WT, Yau YW, See KC. Safe patient transport for COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020; 24:94.15. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:1564–7.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Acute Intestinal Ischemia in a Patient with COVID-19 Infection

- The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on in-hospital mortality in patients admitted through the emergency department

- Intracranial Hypertension after COVID-19 Infection

- The Impact of COVID-19 on Dysphagia in a Steroid-Responsive Dermatomyositis Patient: A Case Report

- A Case Report of Tracheoesophageal Fistula Found during General Anesthesia for Emergency Exploratory Laparotomy