J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg.

2020 Oct;46(5):353-357. 10.5125/jkaoms.2020.46.5.353.

Late reconstruction of extensive orbital floor fracture with a patient-specific implant in a bombing victim

- Affiliations

-

- 1OMFS-IMPATH Research Group, Department of Imaging and Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

- 2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

- KMID: 2508261

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2020.46.5.353

Abstract

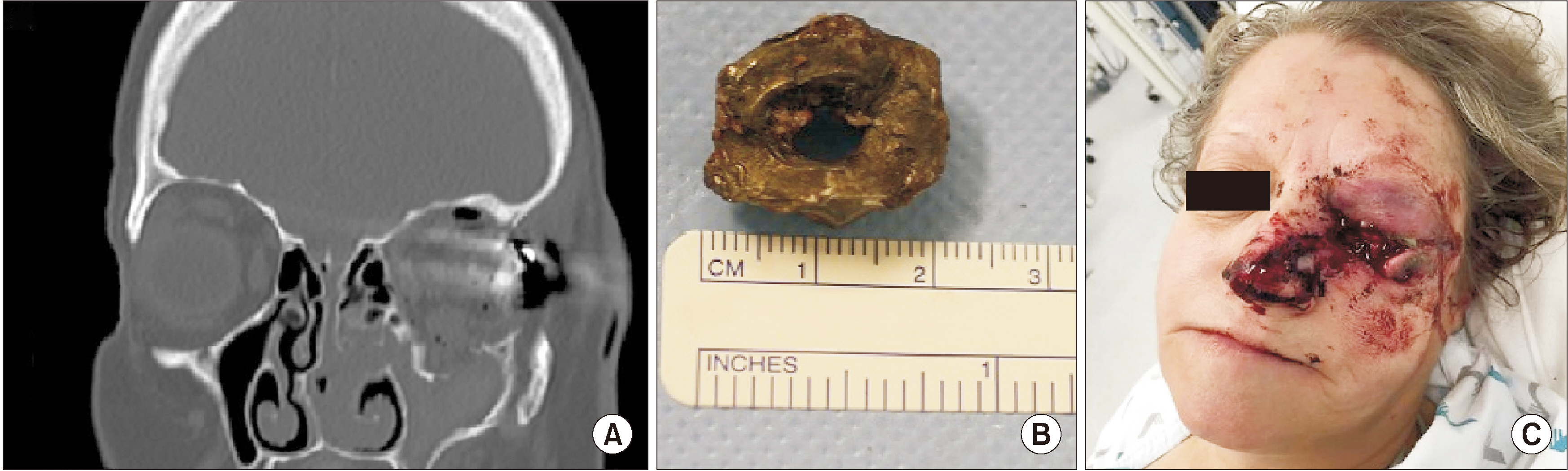

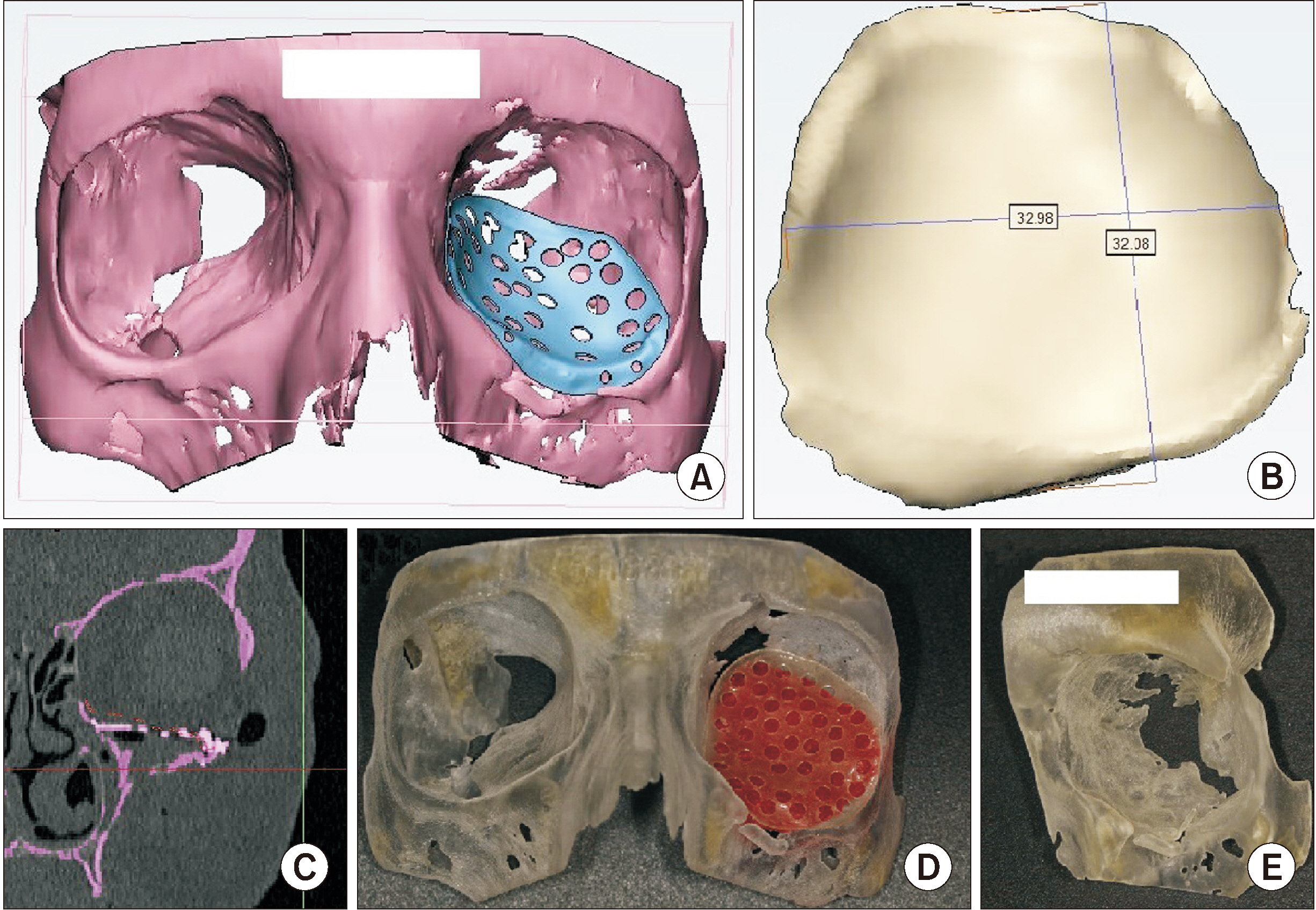

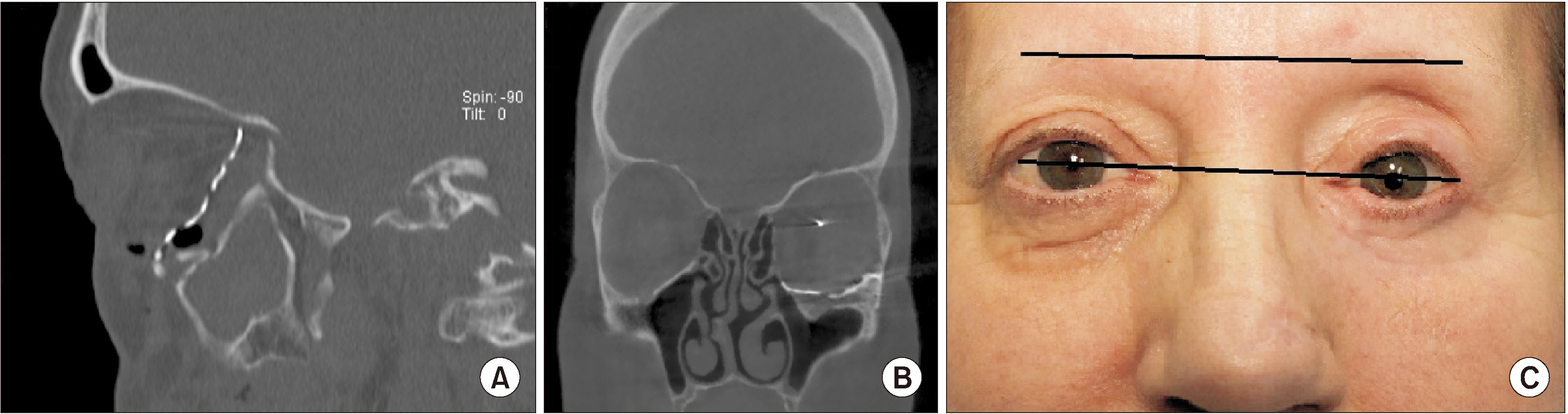

- Fractures of the orbital floor and walls are among the most frequent maxillofacial fractures. Virtual three-dimensional (3D) planning and use of patientspecific implants (PSIs) could improve anatomic and functional outcomes in orbital reconstruction surgery. The presented case was a victim of a terrorist attack involving improvised explosive devices. This 58-year-old female suffered severe wounds caused by a single piece of metal from a bomb, shattering the left orbital floor and lateral orbital wall. Due to remaining hypotropia of the left eye compared to the right eye, late orbital floor reconstruction was carried out with a personalised 3D printed titanium implant. We concluded that this technique with PSI appears to be a viable method to correct complex orbital floor defects. Our research group noted good aesthetic and functional results one year after surgery. Due to the complexity of the surgery for a major bony defect of the orbital floor, it is important that the surgery be executed by experienced surgeons in the field of maxillofacial traumatology.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Ellis E 3rd, Messo E. 2004; Use of nonresorbable alloplastic implants for internal orbital reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 62:873–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.025 . DOI: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.025. PMID: 15218569.

Article2. Bertol LS, Kindlein W Jr, da Silva FP, Aumund-Kopp C. 2010; Medical design: direct metal laser sintering of Ti-6Al-4V. Mater Des. 31:3982–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2010.02.050 . DOI: 10.1016/j.matdes.2010.02.050.

Article3. de Oliveira FM, Salazar-Gamarra R, Öhman D, Nannmark U, Pecorari V, Dib LL. 2018; Quality of life assessment of patients utilizing orbital implant-supported prostheses. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 20:438–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/cid.12602 . DOI: 10.1111/cid.12602. PMID: 29508545.

Article4. Davies JC, Chan HHL, Bernstein JM, Goldstein DP, Irish JC, Gilbert RW. 2018; Orbital floor reconstruction: 3-Dimensional analysis shows comparable morphology of scapular and iliac crest bone grafts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 76:2011–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2018.03.034 . DOI: 10.1016/j.joms.2018.03.034. PMID: 29679587.

Article5. Ilankovan V, Jackson IT. 1992; Experience in the use of calvarial bone grafts in orbital reconstruction. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 30:92–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0266-4356(92)90077-v . DOI: 10.1016/0266-4356(92)90077-V. PMID: 1567810.

Article6. Zhang WB, Mao C, Liu XJ, Guo CB, Yu GY, Peng X. 2015; Outcomes of orbital floor reconstruction after extensive maxillectomy using the computer-assisted fabricated individual titanium mesh technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 73:2065.e1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2015.06.171 . DOI: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.06.171. PMID: 26188101.

Article7. Young SM, Sundar G, Lim TC, Lang SS, Thomas G, Amrith S. 2017; Use of bioresorbable implants for orbital fracture reconstruction. Br J Ophthalmol. 101:1080–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309330 . DOI: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309330. PMID: 27913446.

Article8. Al-Khdhairi OBH, Abdulrazaq SS. 2017; Is orbital floor reconstruction with titanium mesh safe? J Craniofac Surg. 28:e692–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000003864 . DOI: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003864. PMID: 28885440.

Article9. Zimmerer RM, Ellis E 3rd, Aniceto GS, Schramm A, Wagner ME, Grant MP, et al. 2016; A prospective multicenter study to compare the precision of posttraumatic internal orbital reconstruction with standard preformed and individualized orbital implants. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 44:1485–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2016.07.014 . DOI: 10.1016/j.jcms.2016.07.014. PMID: 27519662.

Article10. Hwang WJ, Lee DH, Choi W, Hwang JH, Kim KS, Lee SY. 2017; Analysis of orbital volume measurements following reduction and internal fixation using absorbable mesh plates and screws for patients with orbital floor blowout fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 28:1664–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000003730 . DOI: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003730. PMID: 28834830.

Article11. Oh TS, Jeong WS, Chang TJ, Koh KS, Choi JW. 2016; Customized orbital wall reconstruction using three-dimensionally printed rapid prototype model in patients with orbital wall fracture. J Craniofac Surg. 27:2020–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000003195 . DOI: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003195. PMID: 28005746.

Article12. Purnell CA, Vaca EE, Ellis MF. 2018; Orbital fracture reconstruction using prebent, anatomic titanium plates: technical tips to avoid complications. J Craniofac Surg. 29:e515–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000004563 . DOI: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004563. PMID: 29608480.

Article13. Fan B, Chen H, Sun YJ, Wang BF, Che L, Liu SY, et al. 2017; Clinical effects of 3-D printing-assisted personalized reconstructive surgery for blowout orbital fractures. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 255:2051–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-017-3766-y . DOI: 10.1007/s00417-017-3766-y. PMID: 28786025.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Reconstruction of Orbital Floor Fracture by Grafting Parietal Bone

- Use of a Titanium Buttress to Prevent Implant Displacement in Extensive Orbital Blowout Fracture

- Results of Reconstruction of Orbital Wall Fracture With Bioresorbable Plate

- Simultaneous Transconjunctival and Transantral Approach for Repair of Blowout Fracture by using Medpor Orbital Implant

- Late Complication of a Silicone Implant Thirty Years after Orbital Fracture Reconstruction