J Korean Med Sci.

2020 Oct;35(40):e367. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e367.

Operation and Management of Seoul Metropolitan City Community Treatment Center for Mild Condition COVID-19 Patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Public Healthcare Center, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Laboratory of Emergency Medical Services, Seoul National University Hospital Biomedical Research Institute, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Emergency Medicine, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 4Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Surgery, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 7Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 8Department of Emergency Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2507621

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e367

Abstract

- Background

In response to the disaster of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) established a patient facility for mild condition patients other than hospital. This study was conducted to investigate the operation and necessary resources of a community treatment center (CTC) operated in Seoul, a metropolitan city with a population of 10 million.

Methods

To respond COVID-19 epidemic, the SMG designated 5 municipal hospitals as dedicated COVID-19 hospitals and implemented one CTC cooperated with the Boramae Municipal Hospital for COVID-19 patients in Seoul. As a retrospective cross-sectional observational study, retrospective medical records review was conducted for patients admitted to the Seoul CTC. The admission and discharge route of CTC patients were investigated. The patient characteristics were compared according to route of discharge whether the patient was discharged to home or transferred to hospital. To report the operation of CTC, the daily mean number of tests (reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and chest X-ray) and consultations by medical staffs were calculated per week. The list of frequent used medications and who used medication most frequently were investigated.

Results

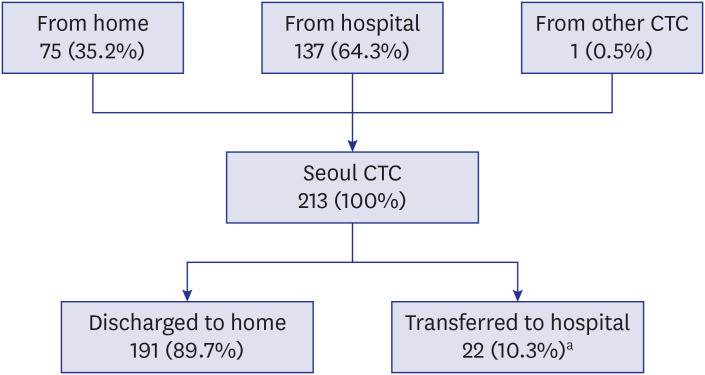

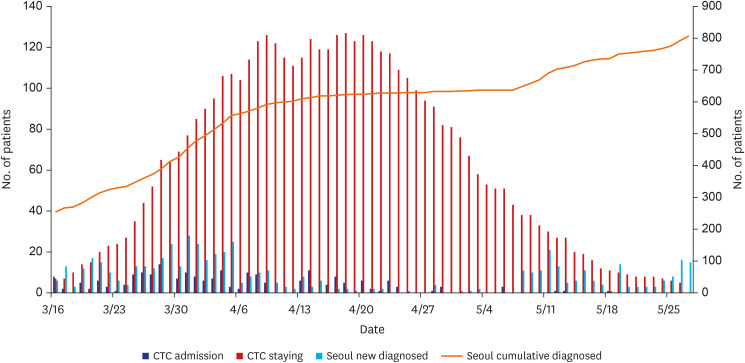

Until May 27 when the Seoul CTC was closed, 26.5% (n = 213) of total 803 COVID-19 patients in Seoul were admitted to the CTC. It was 35.7% (n = 213) of 597 newly diagnosed patients in Seoul during the 11 weeks of operation. The median length of stay was 21 days (interquartile range, 12–29 days). A total of 191 patients (89.7%) were discharged to home after virologic remission and 22 (10.3%) were transferred to hospital for further treatment. Fifty percent of transferred patients were within a week since CTC admission. Daily 2.5–3.6 consultations by doctors or nurses and 0.4–0.9 tests were provided to one patient. The most frequently prescribed medication was symptomatic medication for COVID-19 (cough/ sputum and rhinorrhea). The next ranking was psychiatric medication for sleep problem and depression/anxiety, which was prescribed more than digestive drug.

Conclusion

In the time of an infectious disease disaster, a metropolitan city can operate a temporary patient facility such as CTC to make a surge capacity and appropriately allocate scarce medical resource.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Noji EK, Toole MJ. The historical development of public health responses to disaster. Disasters. 1997; 21(4):366–376. PMID: 9455008.2. Disaster medical services. Ann Emerg Med. 2018; 72(4):e39. PMID: 30236340.3. Hui EK. Reasons for the increase in emerging and re-emerging viral infectious diseases. Microbes Infect. 2006; 8(3):905–916. PMID: 16448839.4. Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza. Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T, Gao Z, Harper SA, Shaw M, et al. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362(18):1708–1719. PMID: 20445182.

Article5. Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, Chan P, Cameron P, Joynt GM, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348(20):1986–1994. PMID: 12682352.

Article6. Nacoti M, Ciocca A, Giupponi A, Brambillasca P, Lussana F, Pisano M, et al. At the epicenter of the Covid-19 pandemic and humanitarian crises in Italy: changing perspectives on preparation and mitigation. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. Forthcoming. 2020.7. Truog RD, Mitchell C, Daley GQ. The toughest triage - allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(21):1973–1975. PMID: 32202721.

Article8. Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages—the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(18):e41. PMID: 32212516.9. Olson DR, Huynh M, Fine A, Baumgartner J, Castro A, Chan HT, et al. Preliminary estimate of excess mortality during the COVID-19 outbreak — New York City, March 11–May 2, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020; 69(19):603–605.10. Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(21):2049–2055. PMID: 32202722.

Article11. Hellewell J, Abbott S, Gimma A, Bosse NI, Jarvis CI, Russell TW, et al. Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. Lancet Glob Health. 2020; 8(4):e488–96. PMID: 32119825.

Article12. Morton MJ, DeAugustinis ML, Velasquez CA, Singh S, Kelen GD. Developments in surge research priorities: a systematic review of the literature following the academic emergency medicine consensus conference, 2007–2015. Acad Emerg Med. 2015; 22(11):1235–1252. PMID: 26531863.13. Fagbuyi DB, Brown KM, Mathison DJ, Kingsnorth J, Morrison S, Saidinejad M, et al. A rapid medical screening process improves emergency department patient flow during surge associated with novel H1N1 influenza virus. Ann Emerg Med. 2011; 57(1):52–59. PMID: 20947207.

Article14. Landman A, Teich JM, Pruitt P, Moore SE, Theriault J, Dorisca E, et al. The Boston Marathon bombings mass casualty incident: one emergency department’s information systems challenges and opportunities. Ann Emerg Med. 2015; 66(1):51–59. PMID: 24997562.

Article15. Westgard BC, Morgan MW, Vazquez-Benitez G, Erickson LO, Zwank MD. An analysis of changes in emergency department visits after a state declaration during the time of COVID-19. Ann Emerg Med. Forthcoming. 2020; DOI: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.06.019.

Article16. Wurmb T, Scholtes K, Kolibay F, Schorscher N, Ertl G, Ernestus RI, et al. Hospital preparedness for mass critical care during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Crit Care. 2020; 24(1):386. PMID: 32605581.

Article17. Kang E, Lee SY, Jung H, Kim MS, Cho B, Kim YS. Operating protocols of a community treatment center for isolation of patients with coronavirus disease, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020; 26(10):2329–2337. PMID: 32568665.

Article18. Lee YH, Hong CM, Kim DH, Lee TH, Lee J. Clinical course of asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic patients with coronavirus disease admitted to community treatment centers, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020; 26(10):2346–2352. PMID: 32568662.

Article19. Choi WS, Kim HS, Kim B, Nam S, Sohn JW. Community treatment centers for isolation of asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic patients with coronavirus disease, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020; 26(10):2338–2345. PMID: 32568663.

Article20. Tanne JH, Hayasaki E, Zastrow M, Pulla P, Smith P, Rada AG. Covid-19: how doctors and healthcare systems are tackling coronavirus worldwide. BMJ. 2020; 368:m1090. PMID: 32188598.

Article21. Kang CR, Lee JY, Park Y, Huh IS, Ham HJ, Han JK, et al. Coronavirus disease exposure and spread from nightclubs, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020; 26(10):2499–2501. PMID: 32633713.

Article22. Park SY, Kim YM, Yi S, Lee S, Na BJ, Kim CB, et al. Coronavirus disease outbreak in call center, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020; 26(8):1666–1670. PMID: 32324530.

Article23. Daugherty Biddison EL, Faden R, Gwon HS, Mareiniss DP, Regenberg AC, Schoch-Spana M, et al. Too many patients… a framework to guide statewide allocation of scarce mechanical ventilation during disasters. Chest. 2019; 155(4):848–854. PMID: 30316913.24. Ji Y, Ma Z, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q. Potential association between COVID-19 mortality and health-care resource availability. Lancet Glob Health. 2020; 8(4):e480. PMID: 32109372.

Article25. Hick JL, Einav S, Hanfling D, Kissoon N, Dichter JR, Devereaux AV, et al. Surge capacity principles: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014; 146(4):Suppl. e1S–e16S. PMID: 25144334.26. Kelen GD, Kraus CK, McCarthy ML, Bass E, Hsu EB, Li G, et al. Inpatient disposition classification for the creation of hospital surge capacity: a multiphase study. Lancet. 2006; 368(9551):1984–1990. PMID: 17141705.

Article27. Wilder-Smith A, Chiew CJ, Lee VJ. Can we contain the COVID-19 outbreak with the same measures as for SARS? Lancet Infect Dis. 2020; 20(5):e102–e107. PMID: 32145768.

Article28. Tang B, Xia F, Tang S, Bragazzi NL, Li Q, Sun X, et al. The effectiveness of quarantine and isolation determine the trend of the COVID-19 epidemics in the final phase of the current outbreak in China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020; 95:288–293. PMID: 32171948.

Article29. Wang TY, Liu HL, Lin CY, Kuo FL, Yang PH, Yeh IJ. Emerging success against Covid-19 pandemic: hospital surge capacity in Taiwan. Ann Emerg Med. 2020; 76(3):374–376. PMID: 32828337.30. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Coronavirus disease-19 main website. Updated 2020. Accessed August 1, 2020. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en.31. Sung HK, Kim JY, Heo J, Seo H, Jang YS, Kim H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of 3,060 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea, January–May 2020. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(30):e280. PMID: 32743995.

Article32. Seoul Metropolitan Government. Seoul COVID-19 information website. Updated 2020. Accessed August 1, 2020. https://www.seoul.go.kr/coronaV/coronaStatus.do.33. Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(6):510–512. PMID: 32283003.

Article34. Hick JL, Hanfling D, Cantrill SV. Allocating scarce resources in disasters: emergency department principles. Ann Emerg Med. 2012; 59(3):177–187. PMID: 21855170.

Article35. Xu S, Li Y. Beware of the second wave of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020; 395(10233):1321–1322. PMID: 32277876.

Article36. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(18):1708–1720. PMID: 32109013.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Community-wide Early Response to COVID-19 in Dongnae-gu of Busan City

- Seventy-two Hours, Targeting Time from First COVID-19 Symptom Onset to Hospitalization

- Experience of Treating Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients in Daegu, South Korea

- Social Capital Trends and the Relationship between Social Capital and COVID-19–Related Behaviors & Perceptions

- Risk factors for the deterioration of patients with mild COVID-19 admitted to a COVID-19 community treatment center