Korean Circ J.

2020 Oct;50(10):880-889. 10.4070/kcj.2020.0198.

Long-term Clinical Outcomes of DrugEluting Stent Malapposition

- Affiliations

-

- 1Regional Cardiocerebrovascular Center, Wonkwang University Hospital, Iksan, Korea

- 2Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, NY, USA

- 3Division of Cardiology, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University Health System, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2507005

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2020.0198

Abstract

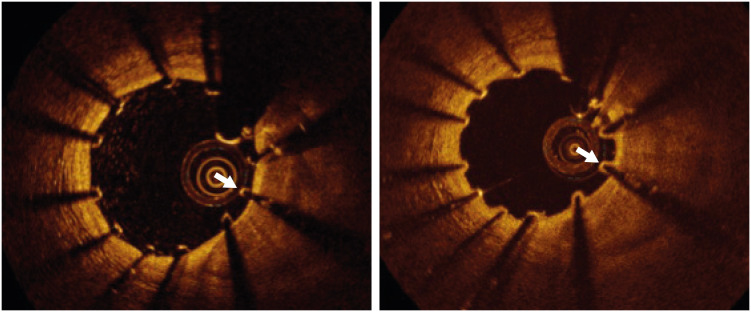

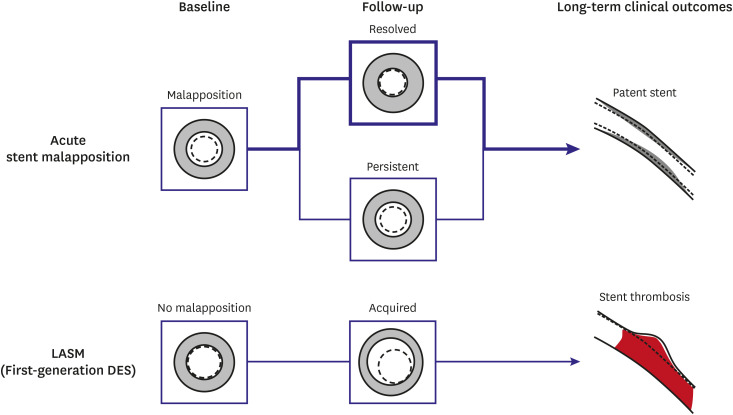

- Previous pathologic, intravascular imaging, and clinical studies have investigated the association between adverse cardiac events and stent malapposition, including acute stent malapposition (ASM, that is detected at index procedure) and late stent malapposition (LSM, that is detected during follow-up) that can be further classified into late-persistent stent malapposition (LPSM, ASM that remains at follow-up) or late-acquired stent malapposition (LASM, newly developed stent malapposition at follow-up that was not present immediately after index stent implantation). ASM has not been associated with adverse cardiac events compared with non-ASM, even in lesions with large-sized malapposition. The clinical outcomes of LSM may depend on its subtype. The recent intravascular ultrasound studies with long-term follow-up have consistently demonstrated that LASM steadily increased the risk of thrombotic events in patients with first-generation drug-eluting stents (DESs). This association has not yet been identified in LPSM. Accordingly, it is reasonable that approaches to stent malapposition should be based on its relationship with clinical outcomes. ASM may be tolerable after successful stent implantation, whereas prolonged anti-thrombotic medications and/or percutaneous interventions to modify LASM may be considered in selected patients with first-generation DESs. However, these treatments are still questionable due to lack of firm evidences.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Attizzani GF, Capodanno D, Ohno Y, Tamburino C. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and clinical aspects of incomplete stent apposition. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63:1355–1367. PMID: 24530675.

Article2. Mintz GS, Nissen SE, Anderson WD, et al. American College of Cardiology clinical expert consensus document on standards for acquisition, measurement and reporting of intravascular ultrasound studies (IVUS). a report of the American College of Cardiology task force on clinical expert consensus documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 37:1478–1492. PMID: 11300468.3. Tearney GJ, Regar E, Akasaka T, et al. Consensus standards for acquisition, measurement, and reporting of intravascular optical coherence tomography studies: a report from the International Working Group for Intravascular Optical Coherence Tomography Standardization and Validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 59:1058–1072. PMID: 22421299.4. Lee SY, Ahn CM, Yoon HJ, et al. Early follow-up optical coherence tomographic findings of significant drug-eluting stent malapposition. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018; 11:e007192. PMID: 30562088.

Article5. Im E, Kim BK, Ko YG, et al. Incidences, predictors, and clinical outcomes of acute and late stent malapposition detected by optical coherence tomography after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014; 7:88–96. PMID: 24425586.

Article6. Wang B, Mintz GS, Witzenbichler B, et al. Predictors and long-term clinical impact of acute stent malapposition: an assessment of dual antiplatelet therapy with drug-eluting stents (ADAPT-DES) intravascular ultrasound substudy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016; 5:e004438. PMID: 28007741.

Article7. Romagnoli E, Gatto L, La Manna A, et al. Role of residual acute stent malapposition in percutaneous coronary interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017; 90:566–575. PMID: 28295990.

Article8. Lee SY, Im E, Hong SJ, et al. Severe acute stent malapposition after drug-eluting stent implantation: effects on long-term clinical outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019; 8:e012800. PMID: 31237187.

Article9. Guo N, Maehara A, Mintz GS, et al. Incidence, mechanisms, predictors, and clinical impact of acute and late stent malapposition after primary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction: an intravascular ultrasound substudy of the harmonizing outcomes with revascularization and stents in acute myocardial infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) trial. Circulation. 2010; 122:1077–1084. PMID: 20805433.10. Kawamori H, Shite J, Shinke T, et al. Natural consequence of post-intervention stent malapposition, thrombus, tissue prolapse, and dissection assessed by optical coherence tomography at mid-term follow-up. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013; 14:865–875. PMID: 23291393.

Article11. Shimamura K, Kubo T, Akasaka T, et al. Outcomes of everolimus-eluting stent incomplete stent apposition: a serial optical coherence tomography analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015; 16:23–28. PMID: 25342855.

Article12. Kolandaivelu K, Swaminathan R, Gibson WJ, et al. Stent thrombogenicity early in high-risk interventional settings is driven by stent design and deployment and protected by polymer-drug coatings. Circulation. 2011; 123:1400–1409. PMID: 21422389.

Article13. Sawaya FJ, Lefèvre T, Chevalier B, et al. Contemporary approach to coronary bifurcation lesion treatment. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016; 9:1861–1878. PMID: 27659563.14. Hong SJ, Kim H, Ahn CM, et al. Coronary artery aneurysm after second-generation drug-eluting stent implantation. Yonsei Med J. 2019; 60:824–831. PMID: 31433580.

Article15. Mintz GS, Shah VM, Weissman NJ. Regional remodeling as the cause of late stent malapposition. Circulation. 2003; 107:2660–2663. PMID: 12771011.

Article16. Hoffmann R, Morice MC, Moses JW, et al. Impact of late incomplete stent apposition after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation on 4-year clinical events: intravascular ultrasound analysis from the multicentre, randomised, RAVEL, E-SIRIUS and SIRIUS trials. Heart. 2008; 94:322–328. PMID: 17761505.

Article17. Cook S, Eshtehardi P, Kalesan B, et al. Impact of incomplete stent apposition on long-term clinical outcome after drug-eluting stent implantation. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:1334–1343. PMID: 22285579.

Article18. Siqueira DA, Abizaid AA, Costa JR, et al. Late incomplete apposition after drug-eluting stent implantation: incidence and potential for adverse clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2007; 28:1304–1309. PMID: 17478457.

Article19. Tanabe K, Serruys PW, Degertekin M, et al. Incomplete stent apposition after implantation of paclitaxel-eluting stents or bare metal stents: insights from the randomized TAXUS II trial. Circulation. 2005; 111:900–905. PMID: 15710761.

Article20. Steinberg DH, Mintz GS, Mandinov L, et al. Long-term impact of routinely detected early and late incomplete stent apposition: an integrated intravascular ultrasound analysis of the TAXUS IV, V, and VI and TAXUS ATLAS workhorse, long lesion, and direct stent studies. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010; 3:486–494. PMID: 20488404.21. Hong MK, Mintz GS, Lee CW, et al. Incidence, mechanism, predictors, and long-term prognosis of late stent malapposition after bare-metal stent implantation. Circulation. 2004; 109:881–886. PMID: 14967732.

Article22. Hong MK, Mintz GS, Lee CW, et al. Late stent malapposition after drug-eluting stent implantation: an intravascular ultrasound analysis with long-term follow-up. Circulation. 2006; 113:414–419. PMID: 16432073.23. Hong MK, Mintz GS, Lee CW, et al. Impact of late drug-eluting stent malapposition on 3-year clinical events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50:1515–1516. PMID: 17919574.

Article24. Lee SY, Ahn JM, Mintz GS, et al. Ten-year clinical outcomes of late-acquired stent malapposition after coronary stent implantation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020; 40:288–295. PMID: 31766872.

Article25. Virmani R, Guagliumi G, Farb A, et al. Localized hypersensitivity and late coronary thrombosis secondary to a sirolimus-eluting stent: should we be cautious? Circulation. 2004; 109:701–705. PMID: 14744976.26. Cook S, Ladich E, Nakazawa G, et al. Correlation of intravascular ultrasound findings with histopathological analysis of thrombus aspirates in patients with very late drug-eluting stent thrombosis. Circulation. 2009; 120:391–399. PMID: 19620501.

Article27. Karalis I, Ahmed TA, Jukema JW. Late acquired stent malapposition: why, when and how to handle? Heart. 2012; 98:1529–1536. PMID: 23001063.

Article28. Lüscher TF, Steffel J, Eberli FR, et al. Drug-eluting stent and coronary thrombosis: biological mechanisms and clinical implications. Circulation. 2007; 115:1051–1058. PMID: 17325255.29. Wilson GJ, Nakazawa G, Schwartz RS, et al. Comparison of inflammatory response after implantation of sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents in porcine coronary arteries. Circulation. 2009; 120:141–149. PMID: 19564562.

Article30. Nakazawa G, Finn AV, Vorpahl M, Ladich ER, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Coronary responses and differential mechanisms of late stent thrombosis attributed to first-generation sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57:390–398. PMID: 21251578.

Article31. Otsuka F, Vorpahl M, Nakano M, et al. Pathology of second-generation everolimus-eluting stents versus first-generation sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents in humans. Circulation. 2014; 129:211–223. PMID: 24163064.

Article32. Rizas KD, Mehilli J. Stent polymers: do they make a difference? Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016; 9:e002943. PMID: 27193905.33. Im E, Hong SJ, Ahn CM, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of late stent malapposition detected by optical coherence tomography after drug-eluting stent implantation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019; 8:e011817. PMID: 30905253.

Article34. Räber L, Mintz GS, Koskinas KC, et al. Clinical use of intracoronary imaging. Part 1: guidance and optimization of coronary interventions. An expert consensus document of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions. Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:3281–3300. PMID: 29790954.

Article35. Souteyrand G, Amabile N, Mangin L, et al. Mechanisms of stent thrombosis analysed by optical coherence tomography: insights from the national PESTO French registry. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:1208–1216. PMID: 26757787.

Article36. Taniwaki M, Radu MD, Zaugg S, et al. Mechanisms of very late drug-eluting stent thrombosis assessed by optical coherence tomography. Circulation. 2016; 133:650–660. PMID: 26762519.

Article37. Adriaenssens T, Joner M, Godschalk TC, et al. Optical coherence tomography findings in patients with coronary stent thrombosis: a report of the PRESTIGE consortium (prevention of late stent thrombosis by an interdisciplinary global European effort). Circulation. 2017; 136:1007–1021. PMID: 28720725.38. Banning AP, Lassen JF, Burzotta F, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for obstructive bifurcation lesions: the 14th consensus document from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention. 2019; 15:90–98. PMID: 31105066.

Article39. Hur SH, Lee BR, Kim SW, et al. Late-acquired incomplete stent apposition after everolimus-eluting stent versus sirolimus-eluting stent implantation in patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. EuroIntervention. 2016; 12:e979–86. PMID: 26403637.

Article40. Palmerini T, Kirtane AJ, Serruys PW, et al. Stent thrombosis with everolimus-eluting stents: meta-analysis of comparative randomized controlled trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012; 5:357–364. PMID: 22668554.

Article41. Doi T, Kataoka Y, Noguchi T, et al. Coronary artery ectasia predicts future cardiac events in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017; 37:2350–2355. PMID: 29051141.42. Kawsara A, Núñez Gil IJ, Alqahtani F, Moreland J, Rihal CS, Alkhouli M. Management of coronary artery aneurysms. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018; 11:1211–1223. PMID: 29976357.43. van der Hoeven BL, Liem SS, Dijkstra J, et al. Stent malapposition after sirolimus-eluting and bare-metal stent implantation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: acute and 9-month intravascular ultrasound results of the MISSION! intervention study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008; 1:192–201. PMID: 19463300.44. Prati F, Romagnoli E, Burzotta F, et al. Clinical impact of OCT findings during PCI: the CLI-OPCI II study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015; 8:1297–1305. PMID: 26563859.45. Soeda T, Uemura S, Park SJ, et al. Incidence and clinical significance of poststent optical coherence tomography findings: one-year follow-up study from a multicenter registry. Circulation. 2015; 132:1020–1029. PMID: 26162917.46. Prati F, Romagnoli E, Gatto L, et al. Clinical impact of suboptimal stenting and residual intrastent plaque/thrombus protrusion in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the CLI-OPCI ACS substudy (Centro per la Lotta Contro L'Infarto-Optimization of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Acute Coronary Syndrome). Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016; 9:e003726. PMID: 27965297.

Article47. Bernelli C, Shimamura K, Komukai K, et al. Impact of culprit plaque and atherothrombotic components on incomplete stent apposition in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with everolimus-eluting stents - an OCTAVIA substudy. Circ J. 2016; 80:895–905. PMID: 26853719.48. Ali ZA, Maehara A, Généreux P, et al. Optical coherence tomography compared with intravascular ultrasound and with angiography to guide coronary stent implantation (ILUMIEN III: OPTIMIZE PCI): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016; 388:2618–2628. PMID: 27806900.

Article49. Boden H, van der Hoeven BL, Liem SS, et al. Five-year clinical follow-up from the MISSION! intervention study: sirolimus-eluting stent versus bare metal stent implantation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, a randomised controlled trial. EuroIntervention. 2012; 7:1021–1029. PMID: 22207227.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Late Stent Thrombosis Associated with Late Stent Malapposition after Drug-Eluting Stenting: A Case Report

- State-of-the-Art Stent Technology to Minimize the Risk of Stent Thrombosis and In-Stent Restenosis: AbluminalCoated Biodegradable Polymer DrugEluting Stent

- Evaluation of complications in long-term prostatic stent indwelling

- The Initial Extent of Malapposition in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Treated with Drug-Eluting Stent: The Usefulness of Optical Coherence Tomography

- Dark Side of Drug-eluting Stent in Contemporary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention