J Pathol Transl Med.

2020 Sep;54(5):396-410. 10.4132/jptm.2020.06.10.

Indirect pathological indicators for cardiac sarcoidosis on endomyocardial biopsy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Pathology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Internal Medicine and Interdisciplinary Program for Bioengineering, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Cardiology Division, Cardiovascular Center, and Cardiac Electrophysiology Lab, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 5Division of Cardiovascular Imaging, Department of Radiology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Forensic Medicine, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- 7Department of Pathology, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, Korea

- 8Department of Radiology, Seoul Metropolitan Government - Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 9Department of Pathology, Sejong Hospital, Bucheon, Korea

- KMID: 2506273

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2020.06.10

Abstract

- Background

The definitive pathologic diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis requires observation of a granuloma in the myocardial tissue. It is common, however, to receive a “negative” report for a clinically probable case. We would like to advise pathologists and clinicians on how to interpret “negative” biopsies.

Methods

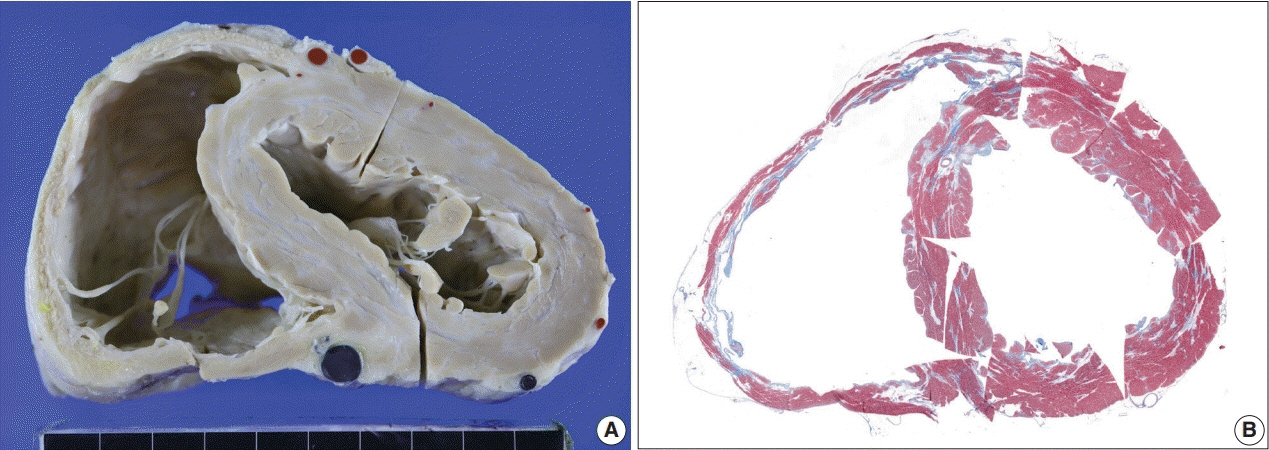

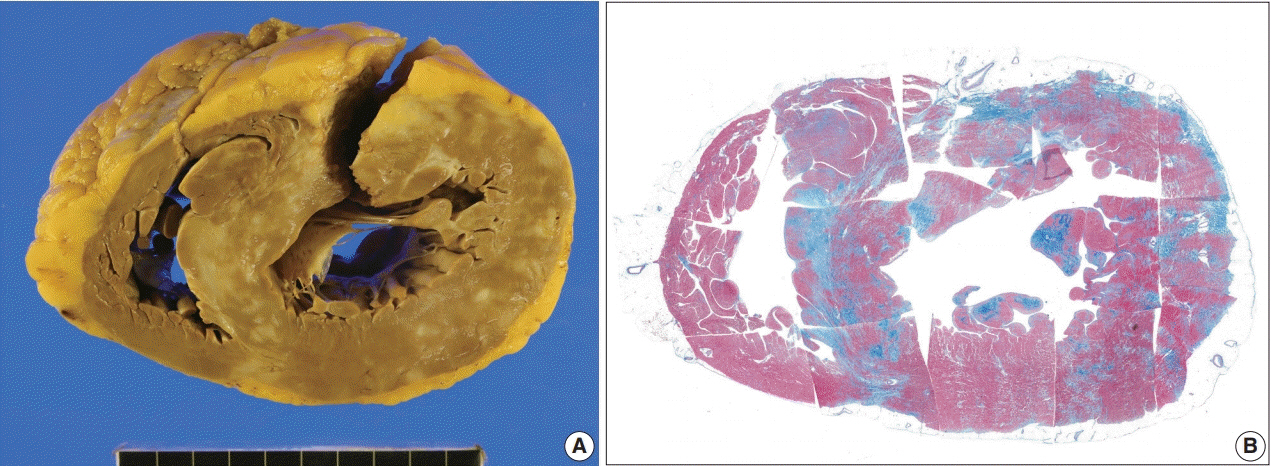

Our study samples were 27 endomyocardial biopsies from 25 patients, three cardiac transplantation and an autopsied heart with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. Pathologic, radiologic, and clinical features were compared.

Results

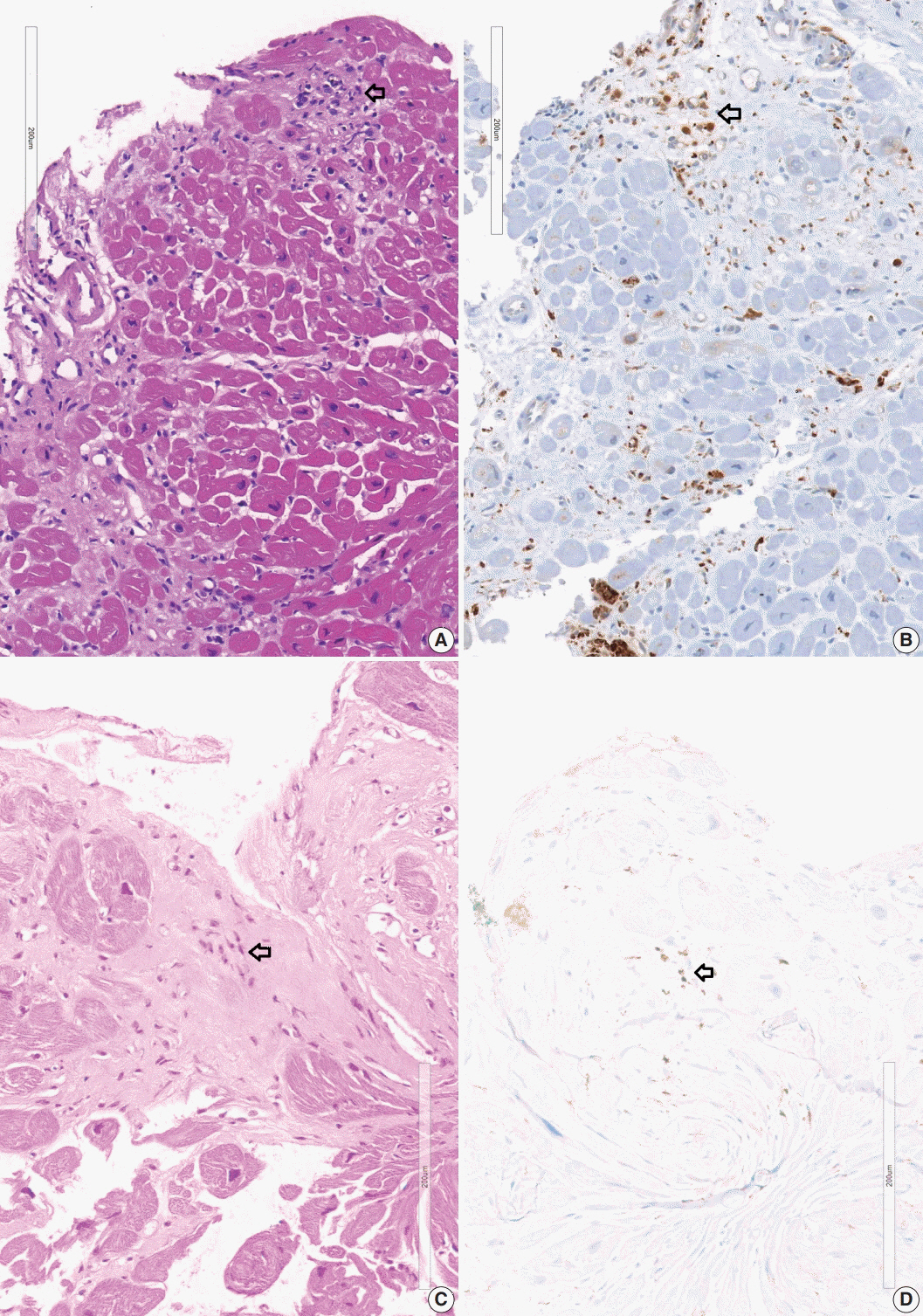

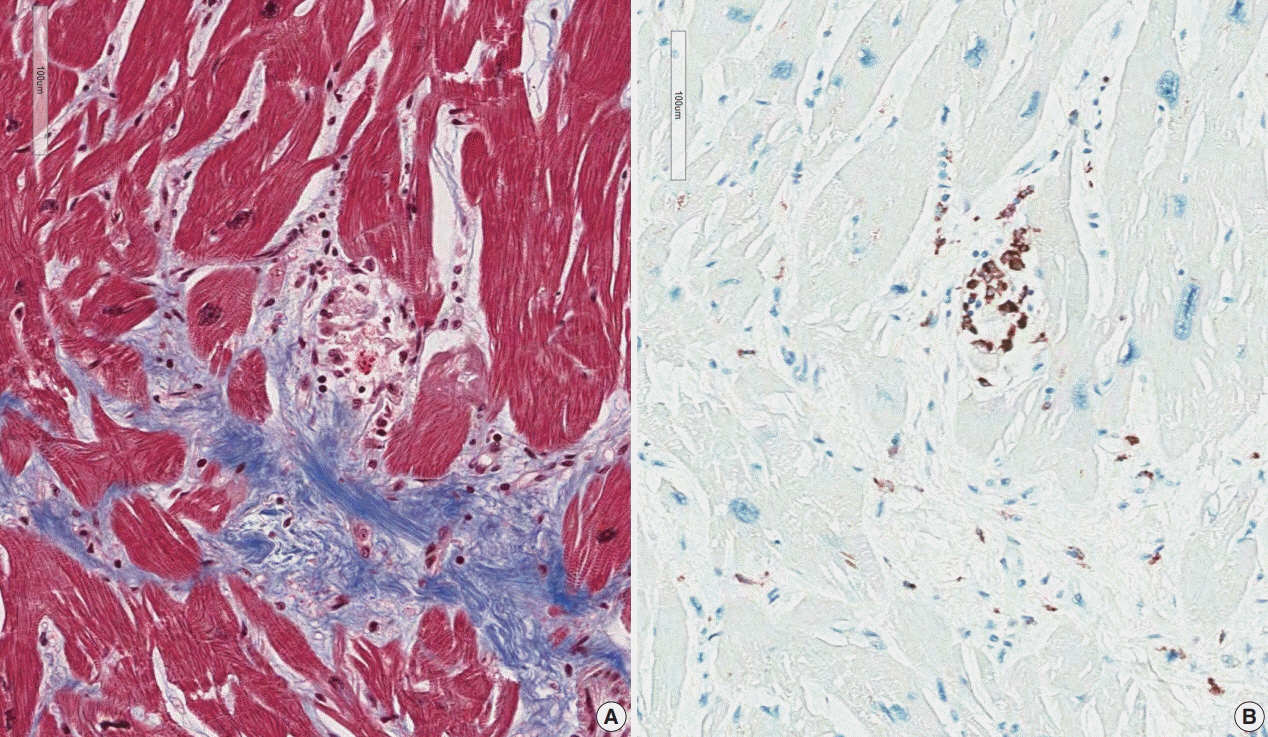

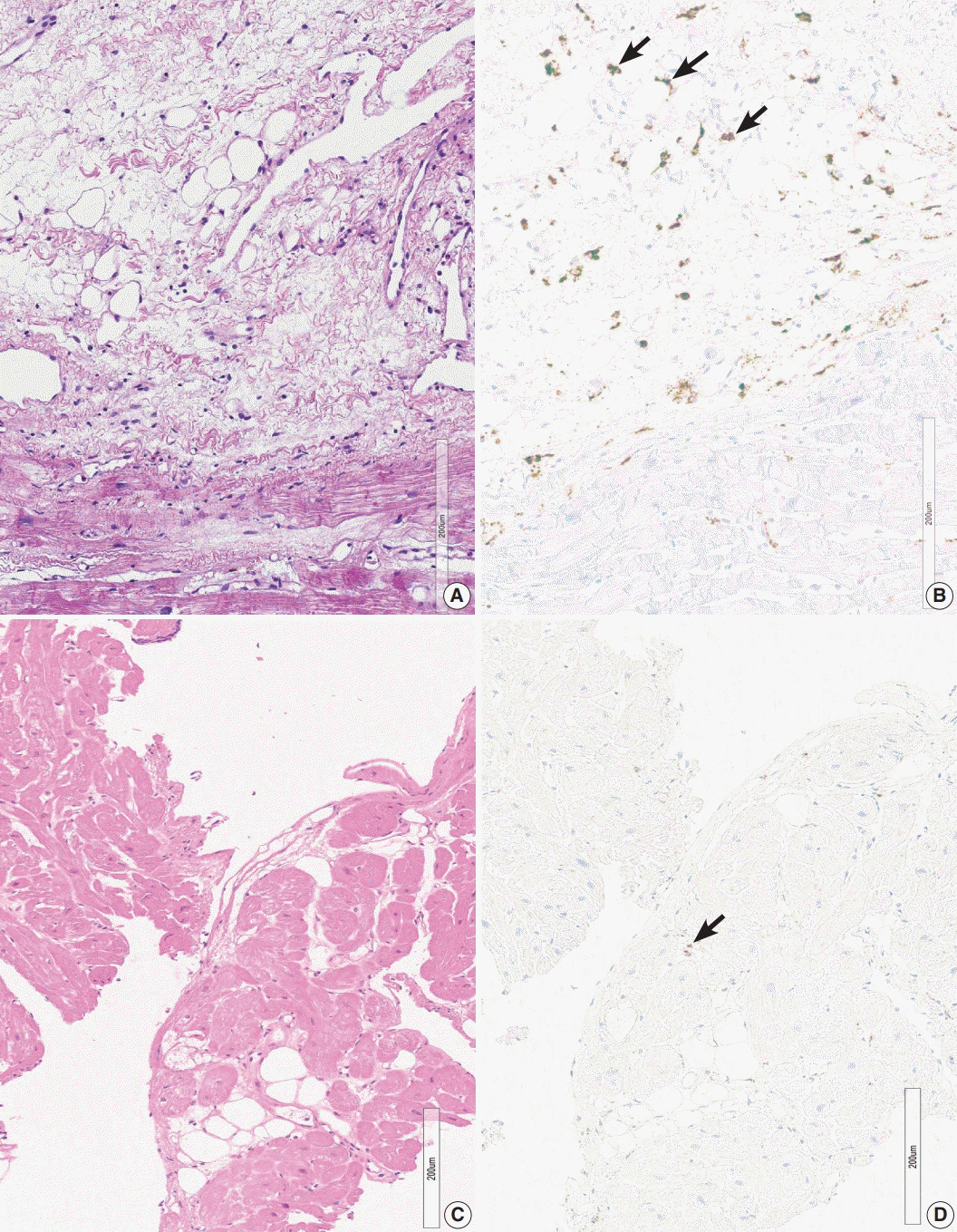

The presence of micro-granulomas or increased histiocytic infiltration was always (6/6 or 100%) associated with fatty infiltration and confluent fibrosis, and they showed radiological features of sarcoidosis. Three of five cases (60%) with fatty change and confluent fibrosis were probable for cardiac sarcoidosis on radiology. When either confluent fibrosis or fatty change was present, one-third (3/9) were radiologically probable for cardiac sarcoidosis. We interpreted cases with micro-granuloma as positive for cardiac sarcoidosis (five of 25, 20%). Cases with both confluent fibrosis and fatty change were interpreted as probable for cardiac sarcoidosis (seven of 25, 28%). Another 13 cases, including eight cases with either confluent fibrosis or fatty change, were interpreted as low probability based on endomyocardial biopsy.

Conclusions

The presence of micro-granuloma could be an evidence for positive diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Presence of both confluent fibrosis and fatty change is necessary for probable cardiac sarcoidosis in the absence of granuloma. Either of confluent fibrosis or fatty change may be an indirect pathological evidence but they are interpreted as nonspecific findings.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Lagana SM, Parwani AV, Nichols LC. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a pathology-focused review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010; 134:1039–46.

Article2. Hamzeh N, Steckman DA, Sauer WH, Judson MA. Pathophysiology and clinical management of cardiac sarcoidosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015; 12:278–88.

Article3. Hulten E, Aslam S, Osborne M, Abbasi S, Bittencourt MS, Blankstein R. Cardiac sarcoidosis-state of the art review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2016; 6:50–63.4. Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336:1224–34.

Article5. Kang EH. Sarcoidosis in Korea: revisited. J Korean Med Assoc. 2008; 51:925–32.

Article6. Mehta D, Lubitz SA, Frankel Z, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients with sarcoidosis: diagnostic and prognostic value of outpatient testing. Chest. 2008; 133:1426–35.7. Longcope WT, Freiman DG. A study of sarcoidosis; based on a combined investigation of 160 cases including 30 autopsies from The Johns Hopkins Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital. Medicine (Baltimore). 1952; 31:1–132.8. Silverman KJ, Hutchins GM, Bulkley BH. Cardiac sarcoid: a clinicopathologic study of 84 unselected patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Circulation. 1978; 58:1204–11.

Article9. Iwai K, Takemura T, Kitaichi M, Kawabata Y, Matsui Y. Pathological studies on sarcoidosis autopsy. II. Early change, mode of progression and death pattern. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1993; 43:377–85.

Article10. Sayah DM, Bradfield JS, Moriarty JM, Belperio JA, Lynch JP 3rd. Cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis: evolving concepts in diagnosis and treatment. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2017; 38:477–98.

Article11. Chapelon-Abric C, de Zuttere D, Duhaut P, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a retrospective study of 41 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004; 83:315–34.12. Birnie DH, Sauer WH, Bogun F, et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014; 11:1305–23.

Article13. Cooper LT, Baughman KL, Feldman AM, et al. The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the management of cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the European Society of Cardiology Endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America and the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007; 28:3076–93.

Article14. Hiraga H, Yuwai K, Hiroe M. Diagnostic standard and guidelines for sarcoidosis. Jpn J Sarcoidosis Granulomatous Disord. 2007; 27:89–102.15. Bhimaraj A, Trachtenberg B, Valderrabano M. Robotically guided left ventricular biopsy to diagnose cardiac sarcoidosis: a multidisciplinary innovation leading to first-in-human case. Circ Heart Fail. 2018; 11:e004627.

Article16. Liang JJ, Hebl VB, DeSimone CV, et al. Electrogram guidance: a method to increase the precision and diagnostic yield of endomyocardial biopsy for suspected cardiac sarcoidosis and myocarditis. JACC Heart Fail. 2014; 2:466–73.17. Casella M, Dello Russo A, Vettor G, et al. Electroanatomical mapping systems and intracardiac echo integration for guided endomyocardial biopsy. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2017; 14:609–19.

Article18. Roberts WC, McAllister HA Jr, Ferrans VJ. Sarcoidosis of the heart. A clinicopathologic study of 35 necropsy patients (group 1) and review of 78 previously described necropsy patients (group 11). Am J Med. 1977; 63:86–108.19. Lee SK, Kim SZ, Kum YS, et al. Sudden death from cardiac sarcoidosis: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 2003; 37:358–61.20. Asakawa N, Uchida K, Sakakibara M, et al. Immunohistochemical identification of Propionibacterium acnes in granuloma and inflammatory cells of myocardial tissues obtained from cardiac sarcoidosis patients. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0179980.

Article21. Fang C, Huang H, Xu Z. Immunological evidence for the role of mycobacteria in sarcoidosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016; 11:e0154716.

Article22. Ratner SJ, Fenoglio JJ Jr, Ursell PC. Utility of endomyocardial biopsy in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Chest. 1986; 90:528–33.

Article23. Yodogawa K, Seino Y, Ohara T, Takayama H, Katoh T, Mizuno K. Effect of corticosteroid therapy on ventricular arrhythmias in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2011; 16:140–7.

Article24. Bagwan IN, Hooper LV, Sheppard MN. Cardiac sarcoidosis and sudden death: the heart may look normal or mimic other cardiomyopathies. Virchows Arch. 2011; 458:671–8.

Article25. Matsui Y, Iwai K, Tachibana T, et al. Clinicopathological study of fatal myocardial sarcoidosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976; 278:455–69.26. Segen JC. The dictionary of modern medicine. Huntington Valley: Farlex Inc;2011.27. Rotterdam H, Korelitz BI, Sommers SC. Microgranulomas in grossly normal rectal mucosa in Crohn’s disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1977; 67:550–4.

Article28. Nakayama T, Sugano Y, Yokokawa T, et al. Clinical impact of the presence of macrophages in endomyocardial biopsies of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017; 19:490–8.

Article29. Sullivan RD, Mayock RL, Jones R Jr. Local injection of hydrocortisone and cortisone into skin lesions of sarcoidosis. J Am Med Assoc. 1953; 152:308–12.

Article30. Sharma OP. Pulmonary sarcoidosis and corticosteroids. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993; 147(6 Pt 1):1598–600.

Article31. Kim MS, Park CK, Shin HJ, et al. Review of sarcoidosis in a province of South Korea from 1996 to 2014. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2017; 80:291–5.

Article32. de Jong S, van Veen TA, van Rijen HV, de Bakker JM. Fibrosis and cardiac arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011; 57:630–8.

Article33. Terasaki F, Ishizaka N. Cardiac sarcoidosis and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: potential differential diagnoses for arrhythmogenic ventricular cardiomyopathy. Intern Med. 2016; 55:1041–2.

Article34. Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation. 2010; 121:1533–41.35. Ponsiglione A, Puglia M, Morisco C, et al. A unique association of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia and acute myocarditis, as assessed by cardiac MRI: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016; 16:230.

Article36. Tavora F, Cresswell N, Li L, Ripple M, Solomon C, Burke A. Comparison of necropsy findings in patients with sarcoidosis dying suddenly from cardiac sarcoidosis versus dying suddenly from other causes. Am J Cardiol. 2009; 104:571–7.

Article37. Shirani J, Roberts WC. Subepicardial myocardial lesions. Am Heart J. 1993; 125(5 Pt 1):1346–52.

Article38. Yang Y, Safka K, Graham JJ, et al. Correlation of late gadolinium enhancement MRI and quantitative T2 measurement in cardiac sarcoidosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014; 39:609–16.

Article39. Shimada T, Shimada K, Sakane T, et al. Diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis and evaluation of the effects of steroid therapy by gadolinium-DTPA-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Med. 2001; 110:520–7.

Article40. Smedema JP, Snoep G, van Kroonenburgh MP, et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 45:1683–90.

Article41. Rosen Y. Pathology of sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 28:36–52.

Article42. Sun BJ, Lee PH, Choi HO, et al. Prevalence of echocardiographic features suggesting cardiac sarcoidosis in patients with pacemaker or implantable cardiac defibrillator. Korean Circ J. 2011; 41:313–20.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Prevalence of Echocardiographic Features Suggesting Cardiac Sarcoidosis in Patients With Pacemaker or Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator

- Heart Transplantation Performed in a Patient with Isolated Cardiac Sarcoidosis

- A Case of Incessant Ventricular Tachycardia Abolished after Endomyocardial Biopsy

- Pathological Analysis of Post-Transplantation Endomyocardial Biopsies

- Systemic Sarcoidosis Presenting with Arrhythmia