Korean J Sports Med.

2020 Sep;38(3):143-150. 10.5763/kjsm.2020.38.3.143.

Objectively Measured Sedentary Behavior and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Physical Education, College of Education, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Physical Education, Korea Military Academy, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2506071

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5763/kjsm.2020.38.3.143

Abstract

- Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between sedentary behavior measured by accelerometer and cardiovascular disease risk factors from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2014–2015.

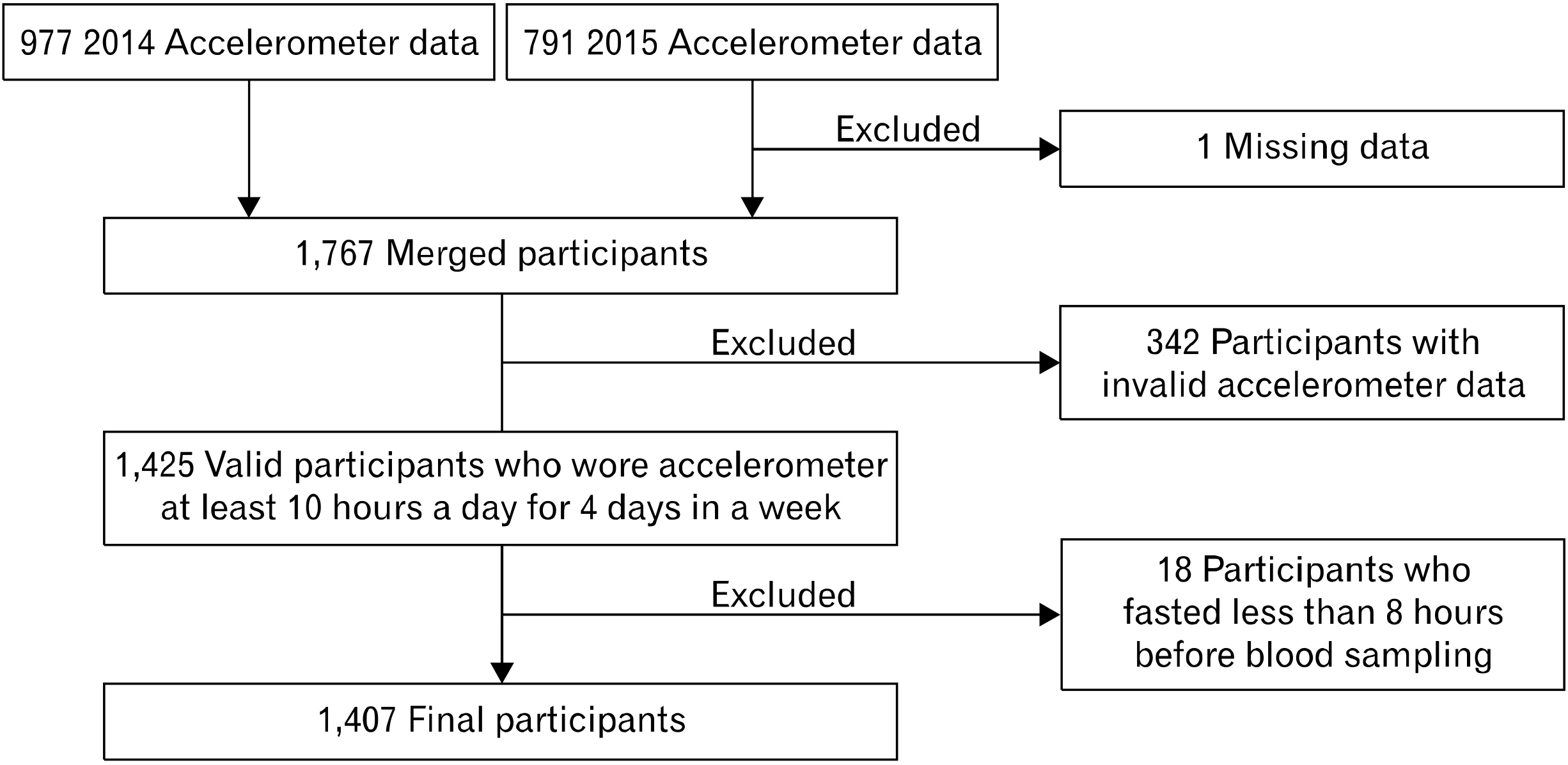

Methods

The participants included in this study volunteered to wear accelerometer (n=1,407). Ordinal logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between sedentary time or sedentary breaks and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the relationship. Covariates were sex, age, educational status, alcohol, smoking, socioeconomic status, body mass index, calorie intake, physical activity, and accelerometer wear time.

Results

The group with the most sedentary time had significantly greater odds of having dyslipidemia (odds ratio, 2.47; 95% confidence interval, 1.54–3.94) compared to the least. There were no other significant relationships between sedentary behavior (sedentary time, sedentary break) and risk factors.

Conclusion

The only significant relationship found in this study was that between sedentary time and dyslipidemia.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Statistics Korea. 2018 Annual report on the causes of death statistics [Internet]. Statistics Korea;Daejeon: Available from: http://kosis.kr/publication/publicationThema. do?pubcode=YD. cited 2020 Jul 1.2. American College of Sports Medicine. 2013. ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;Indianapolis (IN):3. Carter S, Hartman Y, Holder S, Thijssen DH, Hopkins ND. 2017; Sedentary behavior and cardiovascular disease risk: mediating mechanisms. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 45:80–6. DOI: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000106. PMID: 28118158.

Article4. Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, Owen N. 2008; Television time and continuous metabolic risk in physically active adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 40:639–45. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181607421. PMID: 18317383.

Article5. Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW, Winkler EA, Owen N. 2011; Sedentary time and cardio-metabolic biomarkers in US adults: NHANES 2003-06. Eur Heart J. 32:590–7. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq451. PMID: 21224291. PMCID: PMC3634159.

Article6. Park JH, Joh HK, Lee GS, et al. 2018; Association between sedentary time and cardiovascular risk factors in Korean adults. Korean J Fam Med. 39:29–36. DOI: 10.4082/kjfm.2018.39.1.29. PMID: 29383209. PMCID: PMC5788843.

Article7. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. KNHANES regulation for using of accelerometer raw data Ⅵ (2014-2015) [Internet]. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;Cheongju: Available from: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/sub03/sub03_02_02.do. cited 2020 Jul 1.8. Lee H, Lee M, Choi J, Oh K, Kim Y, Kim S. 2018; KNHANES actigraph raw data processing. Korean J Meas Eval Phys Educ Sport Sci. 20:83–94. DOI: 10.35159/kjss.2018.10.27.5.83.9. Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. 2008; Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 40:181–8. DOI: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. PMID: 18091006.

Article10. Atienza AA, Moser RP, Perna F, et al. 2011; Self-reported and objectively measured activity related to biomarkers using NHANES. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 43:815–21. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181fdfc32. PMID: 20962693.

Article11. Tucker JM, Welk GJ, Beyler NK, Kim Y. 2016; Associations between physical activity and metabolic syndrome: comparison between self-report and accelerometry. Am J Health Promot. 30:155–62. DOI: 10.4278/ajhp.121127-QUAN-576. PMID: 25806568.

Article12. Lee M. 2016. A study of physical activity assessment analytic guidelines of Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;Cheongju:13. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. KNHANES regulation for using of raw data 6th (2013-2015) [Internet]. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;Cheongju: Available from: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/sub03/sub03_06_02.do. cited 2020 Jul 1.14. Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, et al. 2008; Breaks in sedentary time: beneficial associations with metabolic risk. Diabetes Care. 31:661–6. DOI: 10.2337/dc07-2046. PMID: 18252901.

Article15. Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. 1972; Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 18:499–502. DOI: 10.1093/clinchem/18.6.499. PMID: 4337382.

Article16. The Korean Society of Hypertension. 2018 Hypertension consultation guide 2018 [Internet]. The Korean Society of Hypertension;Seoul: Available from: http://www.koreanhypertension.org/reference/guide?.mode=read&idno=4246. cited 2018.17. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Korean Academy of Medical Sciences. Standard of diabetes [Internet]. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Korean Academy of Medical Sciences;Seoul: Available from: health.cdc.go.kr/health/HealthInfoArea/ HealthInfo/View.do?idx=2160&page=1&sortType=viewcount&dept=&category_code=&category=1&searchField=titleAndSummary&searchWord=%EB%8B%B9%EB%87%A8&dateSelect=1&fromDate=&toDate=. cited 2020 Jul 1.18. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Korean Academy of Medical Sciences. Standard of dyslipidemia [Internet]. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Korean Academy of Medical Sciences;Seoul: Available from: health.cdc.go.kr/health/HealthInfoArea/ HealthInfo/View.do?idx=160&page=1&sortType=viewcount&dept=&category_code=&category=1&searchField=title&searchWord=%EC%9D%B4%EC%83%81%EC%A7%80%EC%A7%88&dateSelect=1&fromDate=&toDate=#tagID2. cited 2020 Jul 1.19. Ford ES, Caspersen CJ. 2012; Sedentary behaviour and cardiovascular disease: a review of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol. 41:1338–53. DOI: 10.1093/ije/dys078. PMID: 22634869. PMCID: PMC4582407.

Article20. Clark BK, Sugiyama T, Healy GN, Salmon J, Dunstan DW, Owen N. 2009; Validity and reliability of measures of television viewing time and other non-occupational sedentary behaviour of adults: a review. Obes Rev. 10:7–16. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00508.x. PMID: 18631161.

Article21. Clark BK, Healy GN, Winkler EA, et al. 2011; Relationship of television time with accelerometer-derived sedentary time: NHANES. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 43:822–8. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182019510. PMID: 20980928.22. Thorp AA, Healy GN, Winkler E, et al. 2012; Prolonged sedentary time and physical activity in workplace and non-work contexts: a cross-sectional study of office, customer service and call centre employees. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 9:128. DOI: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-128. PMID: 23101767. PMCID: PMC3546308.

Article23. Brocklebank LA, Falconer CL, Page AS, Perry R, Cooper AR. 2015; Accelerometer-measured sedentary time and cardiometabolic biomarkers: a systematic review. Prev Med. 76:92–102. DOI: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.04.013. PMID: 25913420.

Article24. Leon-Latre M, Moreno-Franco B, Andres-Esteban EM, et al. 2014; Sedentary lifestyle and its relation to cardiovascular risk factors, insulin resistance and inflammatory profile. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 67:449–55. DOI: 10.1016/j.rec.2013.10.015. PMID: 24863593.25. Altenburg TM, Lakerveld J, Bot SD, Nijpels G, Chinapaw MJ. 2014; The prospective relationship between sedentary time and cardiometabolic health in adults at increased cardiometabolic risk: the Hoorn Prevention Study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 11:90. DOI: 10.1186/s12966-014-0090-3. PMID: 25027974. PMCID: PMC4132212.

Article26. Hamilton MT, Hamilton DG, Zderic TW. 2007; Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes. 56:2655–67. DOI: 10.2337/db07-0882. PMID: 17827399.

Article27. Parsons TJ, Sartini C, Ellins EA, et al. 2016; Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviour and ankle brachial index: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations in older men. Atherosclerosis. 247:28–34. DOI: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.01.038. PMID: 26854973. PMCID: PMC4819952.

Article28. Huynh QL, Blizzard CL, Sharman JE, Magnussen CG, Dwyer T, Venn AJ. 2014; The cross-sectional association of sitting time with carotid artery stiffness in young adults. BMJ Open. 4:e004384. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004384. PMID: 24604484. PMCID: PMC3948580.

Article29. Kozakova M, Palombo C, Morizzo C, et al. 2010; Effect of sedentary behaviour and vigorous physical activity on segment-specific carotid wall thickness and its progression in a healthy population. Eur Heart J. 31:1511–9. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq092. PMID: 20400760.

Article30. U.S. Deparment of Health and Human Services. Physical activity guidelines for Americans 2018 [Internet]. U.S. Deparment of Health and Human Services;Washington (DC): Available from: https://health.gov/paguidelines/second- edition/pdf/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf. cited 2018.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Association of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior With the Risk of Colorectal Cancer

- Associations Between Screen-Based Sedentary Behavior and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Korean Youth

- Sedentary Time is Associated with Worse Attention in Parkinson’s Disease: A Pilot Study

- Association of Sedentary Time and Physical Activity with the 10-Year Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2014–2017

- Physical Inactivity, Sedentary Behavior and Chronic Diseases