J Bacteriol Virol.

2020 Jun;50(2):132-139. 10.4167/jbv.2020.50.2.132.

Genetic Diversity among Varicella-Zoster Virus Vaccine Strains

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Microbiology, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju 28644, Republic of Korea

- KMID: 2504389

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4167/jbv.2020.50.2.132

Abstract

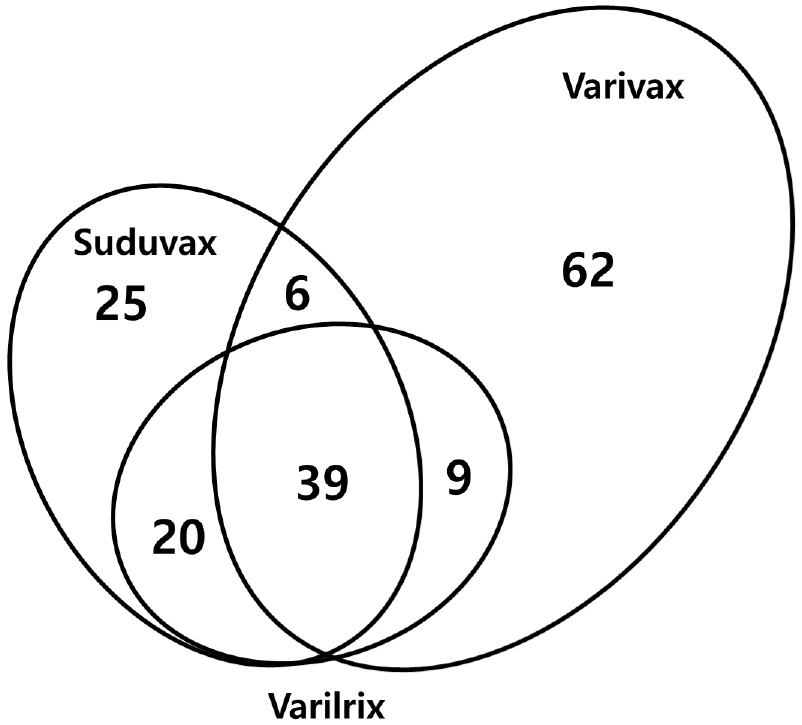

- Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a causative agent for chickenpox in primary infection and shingles after reactivation from latency. Both varicella and zoster can be prevented by live attenuated vaccines, but the molecular mechanism of attenuation is not clearly understood. In this study, the genome sequences of three varicella vaccine strains were analyzed for the genetic diversity including single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and genetic polymorphism. A total of 38 SNPs were identified including 29 substitutions and 9 insertion/deletions. The number of genetically polymorphic sites (GPS) was highest in Varivax and lowest in Varilrix. GPS in the R region including R1, R2, and R3 appeared to be responsible for the genetic polymorphisms in the open reading frame (ORF) 11, 14, and 22 in all three vaccine strains. A relatively large number of GPS were observed in ORF31, 55, and 62, which are known to be essential for virus replication, suggesting that the attenuation of the vaccine strains may be attributed by the diversity of these genes.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Quinlivan M, Breuer J. Molecular studies of Varicella zoster virus. Rev Med Virol 2006;16:225-50.DOI: 10.1002/rmv.502. PMID: 16791838.2. Gershon AA, Gershon MD. Pathogenesis and current approaches to control of varicella-zoster virus infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013;26:728-43.DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00052-13. PMID: 24092852. PMCID: PMC3811230.3. Zerboni L, Sen N, Oliver SL, Arvin AM. Molecular mechanisms of varicella zoster virus pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2014;12:197-210.DOI: 10.1038/nrmicro3215. PMID: 24509782. PMCID: PMC4066823.4. Gilden DH, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Laguardia JJ, Mahalingam R, Cohrs RJ. Neurologic complications of the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus. N Engl J Med 2000;342:635-45.DOI: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420906. PMID: 10699164.5. Takahashi M, Otsuka T, Okuno Y, Asano Y, Yazaki T. Live vaccine used to prevent the spread of varicella in children in hospital. Lancet 1974;2:1288-90.DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)90144-5.6. D'Hondt E, Berge E, Colinet G, Duchene M, Peetermans J. Production and quality control of the Oka-strain live varicella vaccine. Postgrad Med J 1985;61:53-6.7. Kuter BJ, Weibel RE, Guess HA, Matthews H, Morton DH, Neff BJ, et al. Oka/Merck varicella vaccine in healthy children: final report of a 2-year efficacy study and 7-year follow-up studies. Vaccine 1991;9:643-7.DOI: 10.1016/0264-410X(91)90189-D.8. Sohn YM, Park CY, Hwang KK, Woo GJ, Park SY. Safety and immunogenicity of live attenuated varicella virus vaccine (MAV/06 strain). J Korean Ped 1994;37:1405-13.9. Gomi Y, Sunamachi H, Mori Y, Nagaike K, Takahashi M, Yamanishi K. Comparison of the complete DNA sequences of the Oka varicella vaccine and its parental virus. J Virol 2002;76:11447-59.DOI: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11447-11459.2002. PMID: 12388706. PMCID: PMC136748.10. Tillieux SL, Halsey WS, Thomas ES, Voycik JJ, Sathe GM, Vassilev V. Complete DNA sequences of two oka strain varicella-zoster virus genomes. J Virol 2008;82:11023-44.DOI: 10.1128/JVI.00777-08. PMID: 18787000. PMCID: PMC2573284.11. Jeon JS, Won YH, Kim IK, Ahn JH, Shin OS, Kim JH, et al. Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphism among varicella-zoster virus and identification of vaccine-specific sites. Virology 2016;496:277-86.DOI: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.06.017. PMID: 27376245.12. Domingo E, Sheldon J, Perales C. Viral quasispecies evolution. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2012;76:159-216.DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.05023-11. PMID: 22688811. PMCID: PMC3372249.13. Eigen M, Schuster P. The Hypercycle. A principle of natural self-organization. Naturwissenschaften 1977;64:541-65.DOI: 10.1007/BF00450633. PMID: 593400.14. Sauder CJ, Vandenburgh KM, Iskow RC, Malik T, Carbone KM, Rubin SA. Changes in mumps virus neurovirulence phenotype associated with quasispecies heterogeneity. Virology 2006;350:48-57.DOI: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.035. PMID: 16494912.15. Cricca M, Morselli-Labate AM, Venturoli S, Ambretti S, Gentilomi GA, Gallinella G, et al. Viral DNA load, physical status and E2/E6 ratio as markers to grade HPV16 positive women for high-grade cervical lesions. Gynecol Oncol 2007;106:549-57.DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.004. PMID: 17568661.16. Schmutzhard J, Riedel HM, Wirgart BZ, Grillner L. Detection of herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2 and varicella-zoster virus in skin lesions. Comparison of real-time PCR, nested PCR and virus isolation. J Clin Virol 2004;29:120-6.DOI: 10.1016/S1386-6532(03)00113-6.17. Hedrick P. Genetics of populations. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2011.18. Che X, Oliver SL, Sommer MH, Rajamani J, Reichelt M, Arvin AM. Identification and functional characterization of the Varicella zoster virus ORF11 gene product. Virology 2011;412:156-66.DOI: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.055. PMID: 21276599. PMCID: PMC3068617.19. Cohen JI, Seidel KE. Absence of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) glycoprotein V does not alter growth of VZV in vitro or sensitivity to heparin. J Gen Virol 1994;75:3087-93.DOI: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-11-3087. PMID: 7964618.20. González-Motos V, Jürgens C, Ritter B, Kropp KA, Durán V, Larsen O, et al. Varicella zoster virus glycoprotein C increases chemokine-mediated leukocyte migration. PLoS Pathog 2017;13:e1006346.DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006346. PMID: 28542541. PMCID: PMC5444840.21. Kwon KM, Ahn JH. Herpesvirus-encoded deubiquitinating proteases and their roles in regulating immune signaling pathways. J Bacteriol Virol 2013;43:244-52.DOI: 10.4167/jbv.2013.43.4.244.22. Tyler SD, Peters GA, Grose C, Severini A, Gray MJ, Upton C, et al. Genomic cartography of varicella-zoster virus: a complete genome-based analysis of strain variability with implications for attenuation and phenotypic differences. Virology 2007;359:447-58.DOI: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.037. PMID: 17069870.23. Khalil MI, Arvin A, Jones J, Ruyechan WT. A sequence within the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) OriS is a negative regulator of DNA replication and is bound by a protein complex containing the VZV ORF29 protein. J Virol 2011;85:12188-200.DOI: 10.1128/JVI.05501-11. PMID: 21937644. PMCID: PMC3209344.24. Oliver SL, Brady JJ, Sommer MH, Reichelt M, Sung P, Blau HM, et al. An immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif in varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein B regulates cell fusion and skin pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:1911-6.DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1216985110. PMID: 23322733. PMCID: PMC3562845.25. Yang E, Arvin AM, Oliver SL. The glycoprotein B cytoplasmic domain lysine cluster is critical for varicella-zoster virus cell-cell fusion regulation and infection. J Virol 2016;91:e01707-16.DOI: 10.1128/JVI.01707-16. PMID: 27795427. PMCID: PMC5165221.26. Depledge DP, Kundu S, Jensen NJ, Gray ER, Jones M, Steinberg S, et al. Deep sequencing of viral genomes provides insight into the evolution and pathogenesis of varicella zoster virus and its vaccine in humans. Mol Biol Evol 2014;31:397-409.27. Quinlivan M, Breuer J. Clinical and molecular aspects of the live attenuated Oka varicella vaccine. Rev Med Virol 2014;24:254-73.DOI: 10.1002/rmv.1789. PMID: 24687808.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Update in varicella vaccination

- Herpes zoster complicated by deep vein thrombosis : a case report

- Antigen Analysis and Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism of the Polymerase Chain reaction Products of Varicella-Zoster Virus Wild Strains Isolated in Korea

- Two Cases of Herpes Zoster Following Varicella Vaccination in Immunocompetent Young Children: One Case Caused by Vaccine-Strain

- Varicella Vaccine