J Korean Med Sci.

2020 Jun;35(25):e196. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e196.

YouTube as a Source of Information and Education on Hysterectomy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital, College of Medicine, Hallym University, Seoul, Korea

- 2Institute of New Frontier Research, College of Medicine, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea

- KMID: 2503658

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e196

Abstract

- Background

Globally, YouTube is one of the most popular websites, and the content is not restricted to entertainment. The purpose of this study was to assess the quality of information in YouTube videos pertaining to hysterectomy.

Methods

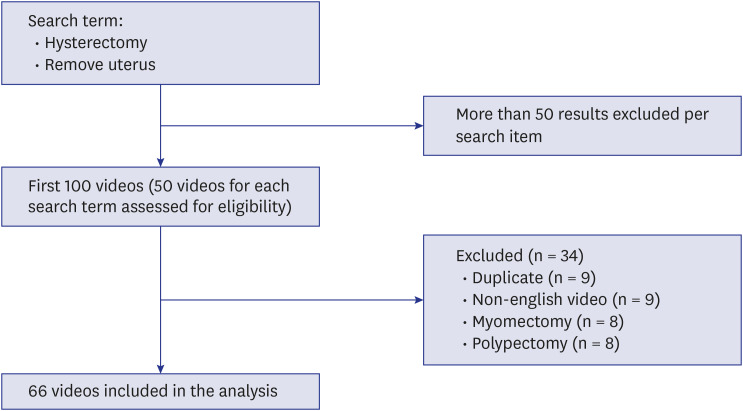

We explored YouTube using the search terms “hysterectomy” and “remove uterus.” The videos that appeared were sorted using the filter “sort by view count.” Of the initial 100 videos, the top 50 videos for each search term were included for review, as determined by the “relevance” filter based on YouTube's algorithm. After excluding 34 videos for various reasons, 66 were included in the final analysis. Each video rated as “useful” was further analyzed for reliability and completeness of information; a set of pre-determined criteria were modified from a previous study and used to grade the quality of videos.

Results

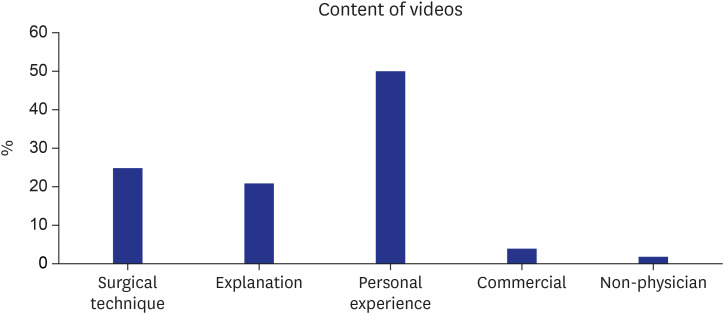

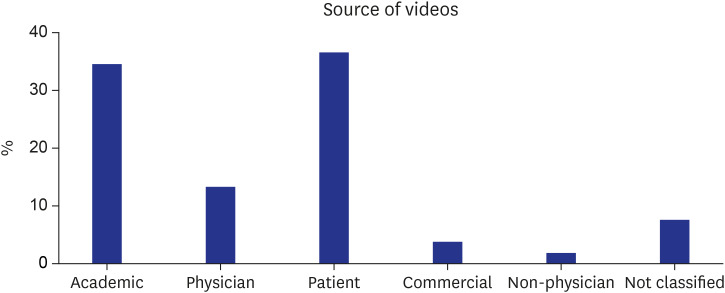

The top 66 videos on hysterectomy had a total of 4,679,118 views. Based on authorship, the videos were categorized as follows: videos uploaded by patients, 37%; academic videos, 35%; videos uploaded by physicians, 13%; commercial videos, 4%; and videos uploaded by non-physicians, 2%. The type of content was also categorized: 50% of the videos recorded personal experiences, 23% recorded surgical techniques, 21% involved explanations of the surgery, and 4% were commercial videos. The majority of the videos made by patients were negatively biased toward hysterectomy surgery (71.72%), while the majority of those made by academics or physicians were surgical educational videos for doctors, not patients.

Conclusion

YouTube is currently not an appropriate source for patients to gain information on hysterectomy. Physicians should be aware of the limitations and provide up-to-date and peer-reviewed content on the website.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Evaluation of YouTube videos as sources of information about complex regional pain syndrome

Aylin Altun, Ayhan Askin, Ilker Sengul, Nazrin Aghazada, Yagmur Aydin

Korean J Pain. 2022;35(3):319-326. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2022.35.3.319.Educational value of spinal injection therapy videos in Korean YouTube for back pain patients

Soo Bin Kim, Seung Bae Cho, Hyogyun Choi, Sehun Lim

Anesth Pain Med. 2022;17(4):429-433. doi: 10.17085/apm.22134.

Reference

-

1. Powell J, Inglis N, Ronnie J, Large S. The characteristics and motivations of online health information seekers: cross-sectional survey and qualitative interview study. J Med Internet Res. 2011; 13(1):e20. PMID: 21345783.

Article2. Bundorf MK, Wagner TH, Singer SJ, Baker LC. Who searches the internet for health information? Health Serv Res. 2006; 41(3 Pt 1):819–836. PMID: 16704514.

Article3. Rice RE. Influences, usage, and outcomes of Internet health information searching: multivariate results from the Pew surveys. Int J Med Inform. 2006; 75(1):8–28. PMID: 16125453.

Article4. Finney Rutten LJ, Agunwamba AA, Wilson P, Chawla N, Vieux S, Blanch-Hartigan D, et al. Cancer-related information seeking among cancer survivors: trends over a decade (2003–2013). J Cancer Educ. 2016; 31(2):348–357. PMID: 25712202.

Article5. Cutrona SL, Mazor KM, Vieux SN, Luger TM, Volkman JE, Finney Rutten LJ. Health information-seeking on behalf of others: characteristics of “surrogate seekers”. J Cancer Educ. 2015; 30(1):12–19. PMID: 24989816.

Article6. Atkinson NL, Saperstein SL, Pleis J. Using the internet for health-related activities: findings from a national probability sample. J Med Internet Res. 2009; 11(1):e4. PMID: 19275980.

Article7. Finney Rutten LJ, Blake KD, Greenberg-Worisek AJ, Allen SV, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Online health information seeking among US adults: measuring progress toward a healthy people 2020 objective. Public Health Rep. 2019; 134(6):617–625. PMID: 31513756.

Article8. YouTube. Updated 2015. Accessed July 30, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/yt/about/press/.9. Briones R, Nan X, Madden K, Waks L. When vaccines go viral: an analysis of HPV vaccine coverage on YouTube. Health Commun. 2012; 27(5):478–485. PMID: 22029723.

Article10. Hansen C, Interrante JD, Ailes EC, Frey MT, Broussard CS, Godoshian VJ, et al. Assessment of YouTube videos as a source of information on medication use in pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016; 25(1):35–44. PMID: 26541372.

Article11. Singh AG, Singh S, Singh PP. YouTube for information on rheumatoid arthritis--a wakeup call? J Rheumatol. 2012; 39(5):899–903. PMID: 22467934.12. Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (3):CD003677. PMID: 19588344.

Article13. Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee opinion No 701: choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 129(6):e155–e159. PMID: 28538495.14. Hegarty E, Campbell C, Grammatopoulos E, DiBiase AT, Sherriff M, Cobourne MT. YouTube™ as an information resource for orthognathic surgery. J Orthod. 2017; 44(2):90–96. PMID: 28463076.

Article15. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977; 33(1):159–174. PMID: 843571.

Article16. Alexa. Updated 2016. Accessed February 1, 2019. https://www.alexa.com/topsites.17. Lee JS, Seo HS, Hong TH. YouTube as a potential training method for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2015; 89(2):92–97. PMID: 26236699.

Article18. Madathil KC, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Greenstein JS, Gramopadhye AK. Healthcare information on YouTube: a systematic review. Health Informatics J. 2015; 21(3):173–194. PMID: 24670899.

Article19. Sampson M, Cumber J, Li C, Pound CM, Fuller A, Harrison D. A systematic review of methods for studying consumer health YouTube videos, with implications for systematic reviews. PeerJ. 2013; 1:e147. PMID: 24058879.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- YouTube as a source of information about rubber dam: quality and content analysis

- Educational value of spinal injection therapy videos in Korean YouTube for back pain patients

- YouTube as a source of patient education information for elbow ulnar collateral ligament injuries: a quality control content analysis

- Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion YouTube Videos as a Source of Patient Education

- Utility Evaluation of Information from YouTube on Breastfeeding for Preterm Babies