Neonatal Med.

2020 May;27(2):65-72. 10.5385/nm.2020.27.2.65.

Current Status of Neonatologist Staffing and Workload in Korean Neonatal Intensive Care Units

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Konyang University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea

- 3Department of Pediatrics, Kyung Hee University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2503161

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5385/nm.2020.27.2.65

Abstract

- Purpose

To identify the recent status of the neonatologist and their workload in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in Korea.

Methods

On October 2018, a survey was conducted on the statistics of the workforce including the census of certified neonatologists, NICU beds, nursing staffing ratings, bed occupancy rate, annual admission of very low birth weight infant (VLBWI), infant acuity score of nursing, and the proportion of out-born patients. The level of neonatal care was self-rated.

Results

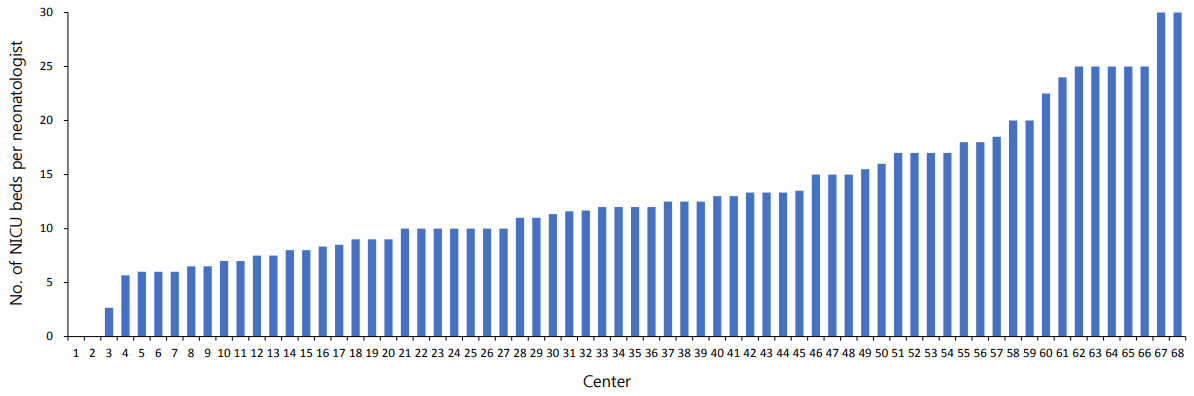

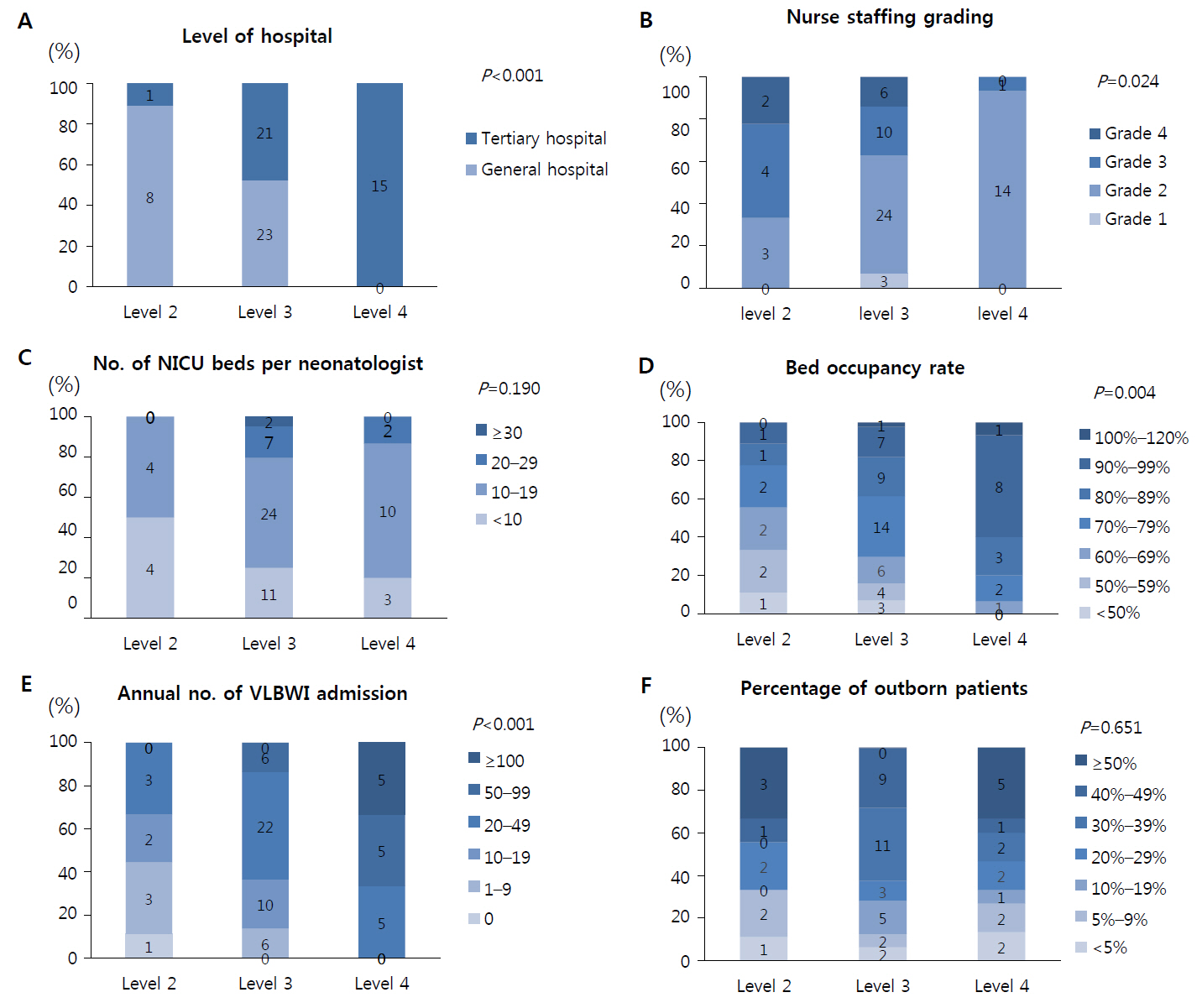

A total of 68 centers responded to the survey. An average number of cer tified neonatologists and the number of NICU beds per center was 1.9 (range, 0 to 5) and 23.1 (range, 0 to 30), respectively. Thirty-eight percent (n=26) of NICUs were being operated with only one (n=24) or no (n=2) certified neonatologist and only 19% (n=13) of NICUs had ≥3 neonatologists. The average ratio of NICU beds to neonatologists rated 13.4±6.2. The higher the level of neonatal care, the higher the number of tertiary referral hospitals, neonatologists, NICU volume, infant acuity scores of nursing, and annual VLBWI admissions. However, there was no difference in the beds to neonatologist ratio between level 2 (n=9, 9.5±3.1), level 3 (n=44, 14.0± 6.9), and level 4 (n=14, 13.7±4.2). The infant acuity score was proportional to the NICU volumes, but not related to the beds to neonatologist ratio.

Conclusion

Compared with the international standards, most Korean NICUs were understaffed in terms of the certified neonatologist and were unable to provide ‘continuity of care’ for high-risk newborns.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Harrison W, Goodman D. Epidemiologic trends in neonatal intensive care, 2007-2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2015; 169:855–62.2. Shin SM, Namgung R, Oh YK, Yoo BH, Jun YH, Lee KH. A survey on the current status of neonatal intensive care units for the planning of regional perinatal care system in Korea. J Korean Soc Neonatol. 1996; 3:1–8.3. Han YJ, Seo K, Shin SM, Lee SW, Do SR, Chang SW. Low birth weight outcomes and policy issues in Korea. Sejong: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;1999.4. Shin SM. Current status and a prospect of neonatal intensive care units in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2006; 49:983–9.5. Shin SM. Current status of neonatal intensive care units in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2008; 51:243–7.6. Kang BH, Jung KA, Hahn WH, Shim KS, Chang JY, Bae CW. Regional analysis on the incidence of preterm and low birth weight infant and the current situation on the neonatal intensive care units in Korea, 2009. J Korean Soc Neonatol. 2011; 18:70–5.7. Kim H. Evaluation of performance and efficiency in operation of neonatal intensive care unit. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2016.8. Shim JW, Jin HS, Bae CW. Changes in survival rate for very-lowbirth-weight infants in Korea: comparison with other countries. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30(Suppl 1):S25–34.9. Lee JH, Noh OK, Chang YS; Korean Neonatal Network. Neonatal outcomes of very low birth weight infants in Korean Neonatal Network from 2013 to 2016. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34:e40.10. Korean Statistical Information Service. Birth statistics [Internet]. Daejeon: KOSIS;2020. [cited 2020 May 11]. Available from: http://www.kosis.kr/index/index.do.11. Song IG, Shin SH, Kim HS. Improved regional disparities in neonatal care by government-led policies in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33:e43.12. Chang YS. Moving forward to improve safety and quality of neonatal intensive care in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33:e89.13. Kim BI. Development of evaluation method and criteria for the appropriateness of neonatal intensive care unit. Wonju: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service;2017.14. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2012; 130:587–97.15. Rogowski JA, Staiger DO, Patrick TE, Horbar JD, Kenny MJ, Lake ET. Nurse staffing in neonatal intensive care units in the United States. Res Nurs Health. 2015; 38:333–41.16. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Manpower needs in neonatal pediatrics. Pediatrics. 1985; 76:132–5.17. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Fetus and New born. Committee of the Section on Perinatal Pediatrics. Estimates of need and recommendations for personnel in neonatal pediatrics. Pediatrics. 1980; 65:850–3.18. Thompson LA, Goodman DC, Little GA. Is more neonatal intensive care always better? Insights from a cross-national comparison of reproductive care. Pediatrics. 2002; 109:1036–43.19. Goodman DC, Fisher ES, Little GA, Stukel TA, Chang CH, Schoendorf KS. The relation between the availability of neonatal intensive care and neonatal mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:1538–44.20. Tucker J; UK Neonatal Staffing Study Group. Patient volume, staffing, and workload in relation to risk-adjusted outcomes in a random stratified sample of UK neonatal intensive care units: a prospective evaluation. Lancet. 2002; 359:99–107.21. Han SJ. High-risk maternal and newborn integrated care centers: status and issues on aspect of pediatric surgery. Korean J Perinatol. 2014; 25:68–74.22. Verloove-Vanhorick SP, Verwey RA, Ebeling MC, Brand R, Ruys JH. Mortality in very preterm and very low birth weight infants according to place of birth and level of care: results of a national collaborative survey of preterm and very low birth weight infants in The Netherlands. Pediatrics. 1988; 81:404–11.23. Phibbs CS, Bronstein JM, Buxton E, Phibbs RH. The effects of patient volume and level of care at the hospital of birth on neonatal mortality. JAMA. 1996; 276:1054–9.24. Phibbs CS, Baker LC, Caughey AB, Danielsen B, Schmitt SK, Phibbs RH. Level and volume of neonatal intensive care and mortality in very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:2165–75.25. Jensen EA, Lorch SA. Effects of a birth hospital's neonatal intensive care unit level and annual volume of very low-birthweight infant deliveries on morbidity and mortality. JAMA Pediatr. 2015; 169:e151906.26. Poets CF, Bartels DB, Wallwiener D. Patient volume and facilities measurements as quality indicators of peri- and neonatal care: a review of data from the last 4 years. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2004; 208:220–5.27. Bartels DB, Wypij D, Wenzlaff P, Dammann O, Poets CF. Hospital volume and neonatal mortality among very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2006; 117:2206–14.28. Chung JH, Phibbs CS, Boscardin WJ, Kominski GF, Ortega AN, Needleman J. The effect of neonatal intensive care level and hospital volume on mortality of very low birth weight infants. Med Care. 2010; 48:635–44.29. Lasswell SM, Barfield WD, Rochat RW, Blackmon L. Perinatal regionalization for very low-birth-weight and very preterm infants: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010; 304:992–1000.30. Shim JW, Kim MJ, Kim EK, Park HK, Song ES, Lee SM, et al. The impact of neonatal care resources on regional variation in neonatal mortality among very low birthweight infants in Korea. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013; 27:216–25.31. British Association of Perinatal Medicine. Optimal arrangements for neonatal intensive care units in the UK including guidance on their medical staffing: a framework for practice (2014) [Internet]. London: BAPM;2014. [cited 2020 May 11]. Available from: https://www.bapm.org/resources/31-optimalarrangements-for-neonatal-intensive-care-units-in-theuk-2014.32. Swiss Society of Neonatology. Standards for levels of neonatal care in Switzerland: revised version 14.3. 2019 [Internet]. Basel: Swiss Society of Neonatology;2019. [cited 2020 May 11]. Available from: https://www.neonet.ch/application/files/7715/6880/5956/Level_Standards_2019-03-14.pdf.33. Bae CW. Bench-marking of Japanese perinatal center system for improving maternal and neonatal outcome in Korea. Korean J Perinatol. 2010; 21:129–39.34. Ministry of Health; Labour and Welfare. Report on NICU maintenance and number of doctors in NICU [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare;2015. [cited 2020 May 11]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-10801000.../0000096037.pdf.35. Ministry of Health; Labour and Welfare. Data on the current status of perinatal medical system [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare;2015. [cited 2020 May 11]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-10801000Iseikyoku-Soumuka/0000096037.pdf.36. Staebler S, Bissinger R. 2016 Neonatal nurse practitioner workforce survey: report of findings. Adv Neonatal Care. 2017; 17:331–6.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Changes in Nurse Staffing Grades in General Wards and Adult and Neonatal Intensive Care Units

- Variations in Nurse Staffing in Adult and Neonatal Intensive Care Units

- Current Status and a Prospect of Neonatal Intensive Care Units in Korea

- Current status of neonatal intensive care units in Korea

- Mortality of very low birth weight infants by neonatal intensive care unit workload and regional group status