J Korean Med Sci.

2020 Jun;35(21):e141. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e141.

Inequalities in Longitudinal Health Trajectories in Middle to Later Life: a Comparison of European Countries and Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Institute of Health Policy and Management, Seoul National University Medical Research Center, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Health Policy and Management, Seoul National University, College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2502241

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e141

Abstract

- Background

This study compared inequalities in the longitudinal trajectory of health measured by latent growth curves (LGCs) in Korea and six other developed European countries.

Methods

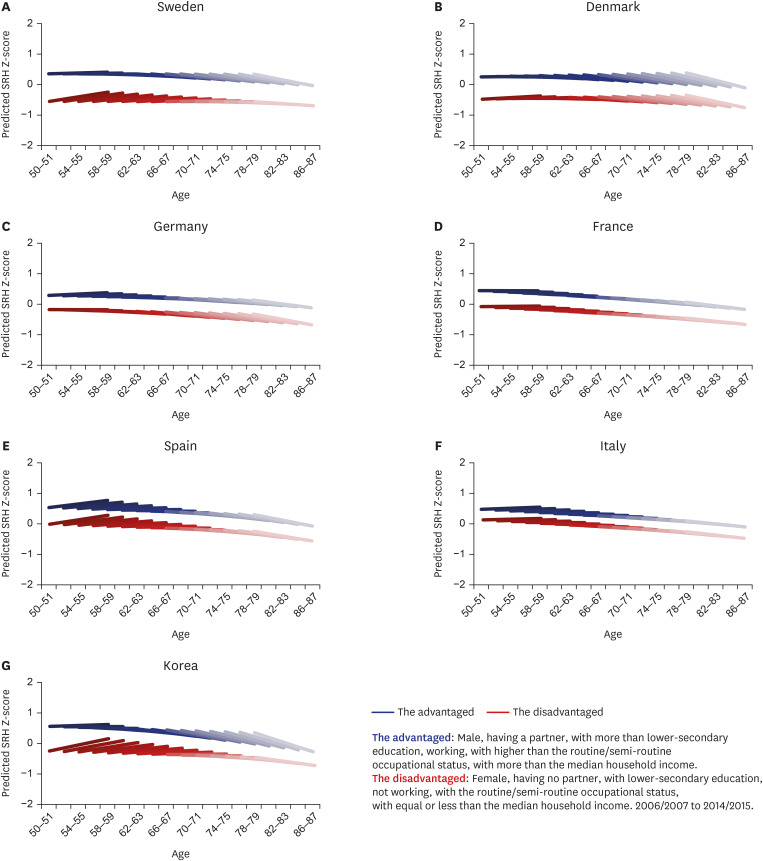

Unconditional and conditional LGCs were fitted, with standardized self-rated health (SRH) as the outcome variable. Two nationally-representative longitudinal datasets were used: the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (2007-2015; 2,761 Swedish, 2,546 Danish, 2,580 German, 2,860 French, 2,372 Spanish, and 2,924 Italian respondents) and the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (2006–2014; 8,465 Korean respondents).

Results

The unconditional patterns of SRH trajectory were similar and unfavorable for women across the countries. Social factors such as education and income generally exerted a significant impact on health trends among older adults. Korea showed less favorable results for the disadvantaged than the advantaged as compared with Denmark, Germany, and France, which was consistent with theoretical expectations. In contrast, the relative SRH trajectory of the disadvantaged as against the advantaged was better as compared with Sweden and worse as compared with Spain/Italy, which was inconsistent with theories that would predict Korea's results were worse than Sweden and similar to Spain/Italy. Women had good SRH trajectory in Denmark and poorer SRH trajectory in Spain, Italy, and Korea, which were consistent. However, women in Sweden showed poorer and mixed outcome, which does not correspond to theoretical predictions.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that it is inconclusive whether Sweden and Denmark (with the most generous welfare arrangements) have better trajectories of health, and Spain, Italy, and Korea (with the least advanced state policies) have worse SRH paths among older adults. However, it can be inferred that Korean governmental policies may have produced a relatively worse context for the less-educated than the six European countries, as well as poorer settings for women than Denmark in terms of their initial SRH status.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Marmot M, Allen J, Goldblatt P, Boyce T, Di McNeish M, Grady IG. 2010.2. Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE, Cavelaars AE, Groenhof F, Geurts JJ. Socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality in western Europe. The EU Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health. Lancet. 1997; 349(9066):1655–1659. PMID: 9186383.3. Vågerö D, Erikson R. Socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality in western Europe. Lancet. 1997; 350(9076):516.

Article4. Tanaka H, Nusselder WJ, Bopp M, Brønnum-Hansen H, Kalediene R, Lee JS, et al. Mortality inequalities by occupational class among men in Japan, South Korea and eight European countries: a national register-based study, 1990-2015. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019; 73(8):750–758. PMID: 31142611.

Article5. Di Cesare M, Khang YH, Asaria P, Blakely T, Cowan MJ, Farzadfar F, et al. Lancet NCD Action Group. Inequalities in non-communicable diseases and effective responses. Lancet. 2013; 381(9866):585–597. PMID: 23410608.

Article6. Sacker A, Worts D, McDonough P. Social influences on trajectories of self-rated health: evidence from Britain, Germany, Denmark and the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011; 65(2):130–136. PMID: 19996360.

Article7. McDonough P, Worts D, Sacker A. Socioeconomic inequalities in health dynamics: a comparison of Britain and the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2010; 70(2):251–260. PMID: 19857919.

Article8. Esping-Andersen G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press;1990.9. Ferrera M. The ‘Southern model’ of welfare in social Europe. J Eur Soc Policy. 1996; 6(1):17–37.

Article10. Holliday I. Productivist welfare capitalism: social policy in East Asia. Polit Stud. 2000; 48(4):706–723.

Article11. Ebbinghaus B. Comparing Welfare State Regimes: Are Typologies an Ideal or Realistic Strategy? Edinburg: ESPAN;2012. p. 1–20.12. Abdul Karim S, Eikemo TA, Bambra C. Welfare state regimes and population health: integrating the East Asian welfare states. Health Policy. 2010; 94(1):45–53. PMID: 19748149.

Article13. United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2016. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme;2016.14. Bahk J, Lynch JW, Khang YH. Forty years of economic growth and plummeting mortality: the mortality experience of the poorly educated in South Korea. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017; 71(3):282–288. PMID: 27707841.

Article15. Tilly C. Big structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation;1984.16. Kim IH, Muntaner C, Vahid Shahidi F, Vives A, Vanroelen C, Benach J. Welfare states, flexible employment, and health: a critical review. Health Policy. 2012; 104(2):99–127. PMID: 22137444.

Article17. Börsch-Supan A, Jürges H. The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe – Methodology. Mannheim: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging (MEA);2005.18. Korea Employment Information Service. Korean longitudinal study of ageing: waves 1–5. Accessed April 14, 2018. http://survey.keis.or.kr/eng/klosa/klosa01.jsp.19. Bergmann M, Kneip T, De Luca G, Scherpenzeel A. SHARE Working Paper Series. Survey Participation in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), Wave 1–7. Munich: SHARE-ERIC;2019.20. Korea Employment Information Service. 2019 KLoSA user's guide. Updated 2018. Accessed August 19, 2019. https://survey.keis.or.kr/klosa/klosaguide/List.jsp.21. Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997; 38(1):21–37. PMID: 9097506.

Article22. Mavaddat N, Parker RA, Sanderson S, Mant J, Kinmonth AL. Relationship of self-rated health with fatal and non-fatal outcomes in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014; 9(7):e103509. PMID: 25076041.

Article23. Haas S. Trajectories of functional health: the ‘long arm’ of childhood health and socioeconomic factors. Soc Sci Med. 2008; 66(4):849–861. PMID: 18158208.

Article24. Wickrama KK, Mancini JA, Kwag K, Kwon J. Heterogeneity in multidimensional health trajectories of late old years and socioeconomic stratification: a latent trajectory class analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013; 68(2):290–297. PMID: 23197341.

Article25. Liang J, Quiñones AR, Bennett JM, Ye W, Xu X, Shaw BA, et al. Evolving self-rated health in middle and old age: how does it differ across Black, Hispanic, and White Americans? J Aging Health. 2010; 22(1):3–26. PMID: 19952367.

Article26. Yoo JP, Yoo MS. Impact of childhood socioeconomic position on self‐rated health trajectories of South Korean adults. Asian Soc Work Policy Rev. 2016; 10(1):142–158.

Article27. Korea Employment Information Service. A guide for imputed variables in KLoSA. Accessed April 13, 2018. https://survey.keis.or.kr/klosa/klosaguide/List.jsp.28. SHARE. SHARE release guide 5.0.0. Updated October 19, 2016. Accessed March 9, 2018. http://www.share-project.org/fileadmin/pdf_documentation/SHARE_release_guide_5-0-0.pdf.29. Muntaner C, Davis O, McIsaack K, Kokkinen L, Shankardass K, O'Campo P. Retrenched welfare regimes still lessen social class inequalities in health: a longitudinal analysis of the 2003–2010 EU-SILC in 23 European countries. Int J Health Serv. 2017; 47(3):410–431. PMID: 28649927.30. Popham F, Dibben C, Bambra C. Are health inequalities really not the smallest in the Nordic welfare states? A comparison of mortality inequality in 37 countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013; 67(5):412–418. PMID: 23386671.

Article31. Sekine M, Chandola T, Martikainen P, Marmot M, Kagamimori S. Socioeconomic inequalities in physical and mental functioning of British, Finnish, and Japanese civil servants: role of job demand, control, and work hours. Soc Sci Med. 2009; 69(10):1417–1425. PMID: 19767137.

Article32. Korea Labor Institute. First Guide on Generated Variables for KLoSA Wave 1. Seoul: Korea Labor Institute;2007.33. SHARE. Scales and multi-item indicators. Updated April 1, 2019. Accessed June 6, 2019. http://www.share-project.org/fileadmin/pdf_documentation/SHARE_Scales_and_Multi-Item_Indicators.pdf.34. Mirowsky J, Kim J. Graphing age trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2007; 35(4):497–541.

Article35. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999; 6(1):1–55.

Article36. Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, Schaap MM, Menvielle G, Leinsalu M, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358(23):2468–2481. PMID: 18525043.

Article37. Leão T, Campos-Matos I, Bambra C, Russo G, Perelman J. Welfare states, the Great Recession and health: trends in educational inequalities in self-reported health in 26 European countries. PLoS One. 2018; 13(2):e0193165. PMID: 29474377.

Article38. Cambois E, Solé-Auró A, Brønnum-Hansen H, Egidi V, Jagger C, Jeune B, et al. Educational differentials in disability vary across and within welfare regimes: a comparison of 26 European countries in 2009. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016; 70(4):331–338. PMID: 26546286.

Article39. Mäki N, Martikainen P, Eikemo T, Menvielle G, Lundberg O, Östergren O, et al. Educational differences in disability-free life expectancy: a comparative study of long-standing activity limitation in eight European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2013; 94:1–8. PMID: 23931939.

Article40. Bakhtiari E, Olafsdottir S, Beckfield J. Institutions, incorporation, and inequality: the case of minority health inequalities in Europe. J Health Soc Behav. 2018; 59(2):248–267. PMID: 29462568.

Article41. Bartley M. Health Inequality: an Introduction to Concepts, Theories and Methods. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons;2016.42. Lee SSY. A comparative study on unemployment insurance, social assistance and ALMP in OECD countries. Korean Soc Policy Rev. 2018; 25(1):345–375.43. Kim YT, Suh JW, Park YJ. The effect of poverty reduction by public pension - a comparative study of 34 OECD countries. Korean Soc Policy Rev. 2018; 25(4):301–321.44. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. The official website of Denmark: the Danish labour market. Accessed January 2, 2018. https://denmark.dk/society-and-business/the-danish-labour-market.45. Rugulies R, Aust B, Burr H, Bültmann U. Job insecurity, chances on the labour market and decline in self-rated health in a representative sample of the Danish workforce. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008; 62(3):245–250. PMID: 18272740.

Article46. Choi YJ, Kim HY. Analyzing changes and determinants of self-rated health during adolescence: a latent growth analysis. Child Health Nurs Res. 2018; 24(4):496–505.

Article47. Kim Y, Jeong M. Predictors of physical health trajectory among middle- and older adults - focusing on impacts of retirement characteristics. J Community Welf. 2018; 64(3):1–24.48. World Economic Forum. The Global Gender Gap Report 2017. Geneva: World Economic Forum;2017.49. Palència L, De Moortel D, Artazcoz L, Salvador-Piedrafita M, Puig-Barrachina V, Hagqvist E, et al. Gender policies and gender inequalities in health in Europe: results of the SOPHIE project. Int J Health Serv. 2017; 47(1):61–82. PMID: 27530991.50. Olafsdottir S. Gendered health inequalities in mental well-being? The Nordic countries in a comparative perspective. Scand J Public Health. 2017; 45(2):185–194. PMID: 28077063.

Article51. Hanibuchi T, Nakaya T, Murata C. Socio-economic status and self-rated health in East Asia: a comparison of China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. Eur J Public Health. 2012; 22(1):47–52. PMID: 21113030.

Article52. Lundberg O, Yngwe MÅ, Stjärne MK, Elstad JI, Ferrarini T, Kangas O, et al. The role of welfare state principles and generosity in social policy programmes for public health: an international comparative study. Lancet. 2008; 372(9650):1633–1640. PMID: 18994660.

Article53. Högberg B. Gender and health among older people: what is the role of social policies? Int J Soc Welf. 2018; 27(3):236–247.

Article54. Shuey KM, Willson AE. Cumulative disadvantage and black-white disparities in life-course health trajectories. Res Aging. 2008; 30(2):200–225.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Identifying Trajectories of Health-related Quality of Life in Mid-life Transition Women: Secondary Data Analysis of Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women & Families

- Depressive Symptom Trajectories and Associated Risks among Korean Elderly

- Trajectories, Transitions, and Trends in Frailty among Older Adults: A Review

- Lifecourse Approaches to Socioeconomic Health Inequalities

- The Proposal of Policies Aimed at Tackling Health Inequalities in Korea