J Educ Eval Health Prof.

2020;17:6. 10.3352/jeehp.2020.17.6.

Correlations between moral courage scores and social desirability scores among medical residents and fellows in Argentina

- Affiliations

-

- 1School of Medicine, Buenos Aires University, Buenos Aires, Argentina

- 2Medical Education Research Laboratory, Hospital Alemán, Buenos Aires, Argentina

- KMID: 2502192

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2020.17.6

Abstract

- Purpose

Moral courage refers to the conviction to take action on one’s ethical beliefs despite the risk of adverse consequences. This study aimed to evaluate correlations between social desirability scores and moral courage scores among medical residents and fellows, and to explore gender- and specialty-based differences in moral courage scores.

Methods

In April 2018, the Moral Courage Scale for Physicians (MCSP), the Professional Moral Courage (PMC) scale and the Marlowe-Crowne scale to measure social desirability were administered to 87 medical residents from Hospital Alemán in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Results

The Cronbach α coefficients were 0.78, 0.74, and 0.81 for the Marlowe-Crowne, MCSP, and PMC scales, respectively. Correlation analysis showed that moral courage scores were weakly correlated with social desirability scores, while both moral courage scales were strongly correlated with each other. Physicians who were training in a surgical specialty showed lower moral courage scores than nonsurgical specialty trainees, and men from any specialty tended to have lower moral courage scores than women. Specifically, individuals training in surgical specialties ranked lower on assessments of the “multiple values,” “endurance of threats,” and “going beyond compliance” dimensions of the PMC scale. Men tended to rank lower than women on the “multiple values,” “moral goals,” and “endurance of threats” dimensions.

Conclusion

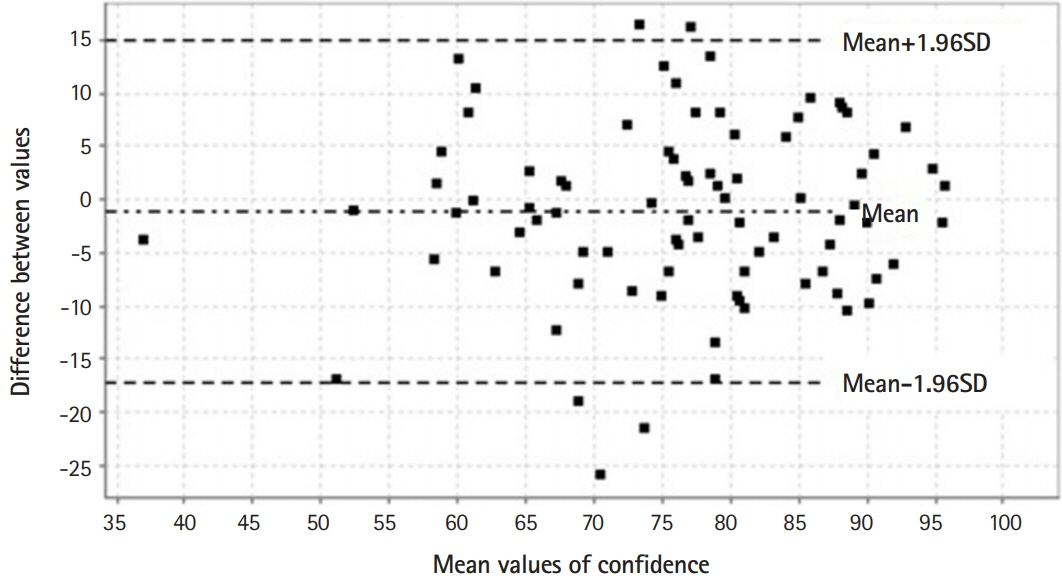

There was a poor correlation between 2 validated moral courage scores and social desirability scores among medical residents and fellows in Argentina. Conversely, both moral courage tools showed a close correlation and concordance, suggesting that these scales are reasonably interchangeable.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Martinez W, Bell SK, Etchegaray JM, Lehmann LS. Measuring moral courage for interns and residents: scale development and initial psychometrics. Acad Med. 2016; 91:1431–1438. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001288.

Article2. McCartney M. Courage is treating patients with Ebola. BMJ. 2014; 349:g4987. https:/doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g4987.

Article3. Sekerka LE, Bagozzi RP, Charnigo R. Facing ethical challenges in the workplace: conceptualizing and measuring professional moral courage. J Bus Ethics. 2009; 89:565–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-0017-5.

Article4. Howard MC, Farr JL, Grandey AA, Gutworth MB. The creation of the workplace social courage scale (WSCS): an investigation of internal consistency, psychometric properties, validity, and utility. J Bus Psychol. 2017; 32:673–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9463-8.

Article5. Hannah ST, Schaubroeck JM, Peng AC, Lord RG, Trevino LK, Kozlowski SW, Avolio BJ, Dimotakis N, Doty J. Joint influences of individual and work unit abusive supervision on ethical intentions and behaviors: a moderated mediation model. J Appl Psychol. 2013; 98:579–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032809.

Article6. Ferrando PJ, Chico E. A Spanish version of the Marlowe and Crowne’s social desirability scale. Psicothema. 2000; 12:383–389.7. Gignac GE, Szodorai ET. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Pers Individ Dif. 2016; 102:74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069.

Article8. Wessa P. Bagplot (v1.0.3) in Free Statistics Software (v1.2.1) [Internet]. [place unknown]: Office for Research Development and Education;2017. [cited 2020 Feb 2]. Available from: https://www.wessa.net/.9. Van de Mortel TF. Faking it: social desirability response bias in self-report research. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2008; 25:40–48.10. Perinelli E, Gremigni P. Use of social desirability scales in clinical psychology: a systematic review. J Clin Psychol. 2016; 72:534–551. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22284.

Article11. Gutierrez S, Sanz J, Espinosa R, Gesteira C, Garcia-Vera MP. The Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale: norms for the Spanish general population and development of a short version. An Psychol. 2016; 32:206–217. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.1.185471.

Article12. Vu A, Tran N, Pham K, Ahmed S. Reliability of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale in Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, and Uganda. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011; 11:162. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-162.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparative Effectiveness of a 30-minute Online Lecture on Abdominal Ultrasonography in the Post-COVID-19 era: A Multi-center Study

- Changes in Nursing Students' Moral Judgment and Ways to Evaluate the Effect of Ethics Education

- An Analysis of the Relationship between Grit and the Psychological Well-Being of Psychiatry Residents

- Effect of Ethics Education on Nurse's Moral Judgement

- Correlations of Communication and Interpersonal Skills between Medical Students and Residents