Yeungnam Univ J Med.

2020 Jan;37(1):47-53. 10.12701/yujm.2019.00346.

Clinical factors that affect the pregnancy rate in frozen-thawed embryo transfer in the freeze-all policy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pusan National University Hospital, Pusan National University School of Medicine, Busan, Korea

- KMID: 2501407

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12701/yujm.2019.00346

Abstract

- Background

This study was conducted to analyze clinical factors that can affect pregnancy rates in normal responders undergoing the freeze-all policy in in vitro fertilization.

Methods

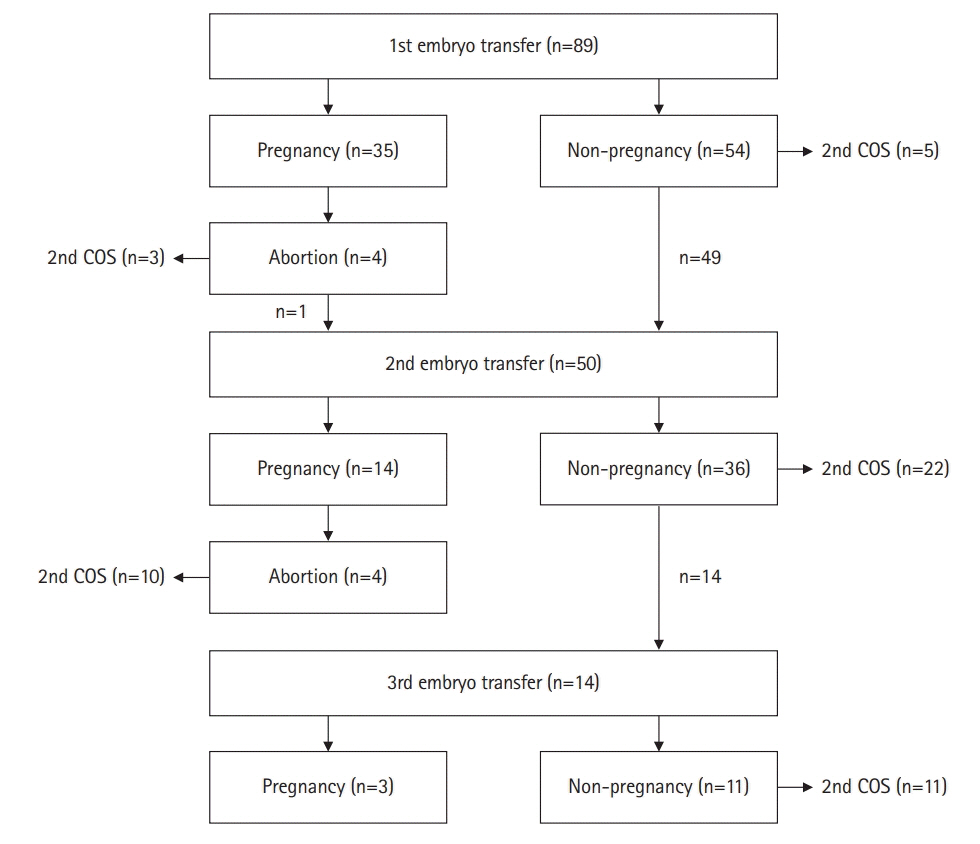

We evaluated 153 embryo transfer cycles in 89 infertile women with normal response to controlled ovarian stimulation (COS). After COS, all embryos were cultured to the blastocyst stage, and good quality blastocysts were vitrified for elective frozen-thawed embryo transfer (FET). Clinical variables associated with COS and the results of COS and culture, including the number of retrieved oocytes, fertilized oocytes, and frozen blastocysts were compared between the pregnant group and the non-pregnant group.

Results

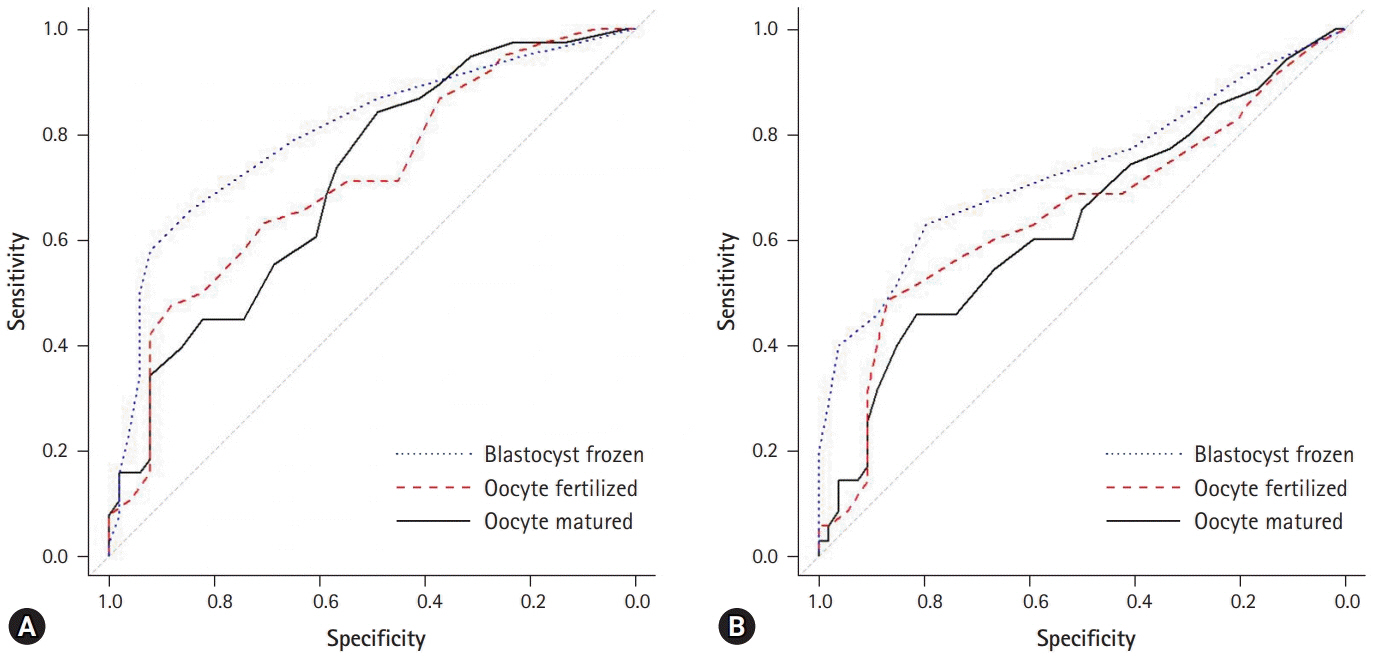

After a single cycle of COS for each patient, 52 patients became pregnant while 37 did not. Significant differences were observed in the number of matured oocytes, fertilized oocytes, frozen blastocysts, and transferred embryos. The number of frozen blastocysts in the pregnant group was almost twice that in the non-pregnant group (5.6±3.1 vs. 2.8±1.9, p<0.001). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for the 4 frozen blastocysts was 0.801 in the pregnant group.

Conclusion

In the freeze-all policy, the number of matured oocytes, number of fertilized oocytes, and number of frozen blastocysts might be predictive factors for pregnancy.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, Garner FC, Aguirre M, Hudson C. Clinical rationale for cryopreservation of entire embryo cohorts in lieu of fresh transfer. Fertil Steril. 2014; 102:3–9.

Article2. Maheshwari A, Pandey S, Shetty A, Hamilton M, Bhattacharya S. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in singleton pregnancies resulting from the transfer of frozen thawed versus fresh embryos generated through in vitro fertilization treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012; 98:368–77.3. Devroey P, Polyzos NP, Blockeel C. An OHSS-Free Clinic by segmentation of IVF treatment. Hum Reprod. 2011; 26:2593–7.

Article4. Blockeel C, Drakopoulos P, Santos-Ribeiro S, Polyzos NP, Tournaye H. A fresh look at the freeze-all protocol: a SWOT analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016; 31:491–7.

Article5. Veleva Z, Orava M, Nuojua-Huttunen S, Tapanainen JS, Martikainen H. Factors affecting the outcome of frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 2013; 28:2425–31.

Article6. Son JB, Jeong JE, Joo JK, Na YJ, Kim CW, Lee KS. Measurement of endometrial and uterine vascularity by transvaginal ultrasonography in predicting pregnancy outcome during frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014; 40:1661–7.

Article7. Roque M, Lattes K, Serra S, Solà I, Geber S, Carreras R, et al. Fresh embryo transfer versus frozen embryo transfer in in vitro fertilization cycles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2013; 99:156–62.8. Ishihara O, Kuwahara A, Saitoh H. Frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer reduces ectopic pregnancy risk: an analysis of single embryo transfer cycles in Japan. Fertil Steril. 2011; 95:1966–9.

Article9. Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, De Leon L, Garner FC, Aguirre M, Hudson C. Frozen-thawed embryo transfer is associated with a significantly reduced incidence of ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2012; 98:1490–4.10. Ishihara O, Araki R, Kuwahara A, Itakura A, Saito H, Adamson GD. Impact of frozen-thawed single-blastocyst transfer on maternal and neonatal outcome: an analysis of 277,042 single-embryo transfer cycles from 2008 to 2010 in Japan. Fertil Steril. 2014; 101:128–33.

Article11. Kalra SK, Ratcliffe SJ, Coutifaris C, Molinaro T, Barnhart KT. Ovarian stimulation and low birth weight in newborns conceived through in vitro fertilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 118:863–71.

Article12. Basile N, Garcia-Velasco JA. The state of "freeze-for-all" in human ARTs. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016; 33:1543–50.

Article13. Roque M, Valle M, Guimarães F, Sampaio M, Geber S. Cost-effectiveness of the freeze-all policy. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2015; 19:125–30.

Article14. Roque M, Valle M, Guimarães F, Sampaio M, Geber S. Freeze-all cycle for all normal responders? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017; 34:179–85.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Analysis of Factors Affecting Survival and Pregnancy Rate in Frozen-thawed Embryo Transfers

- A retrospective study of single frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer

- Effect of Cryopreservation Day on Pregnancy Outcomes in Frozen-thawed Blastocyst Transfer

- Clinical outcomes of frozen embryo transfer cycles after freeze-all policy to prevent ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

- Blastocyst transfer in frozen-thawed cycles