Ann Rehabil Med.

2020 Feb;44(1):77-84. 10.5535/arm.2020.44.1.77.

Changes in Aerobic Capacity Over Time in Elderly Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction During Cardiac Rehabilitation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, Chonnam National University Medical School and Hospital, Gwangju, Korea

- KMID: 2501048

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2020.44.1.77

Abstract

Objective

To test the hypothesis that a longer duration of phase II cardiac rehabilitation is required to recover the exercise capacity of elderly patients compared to younger patients.

Methods

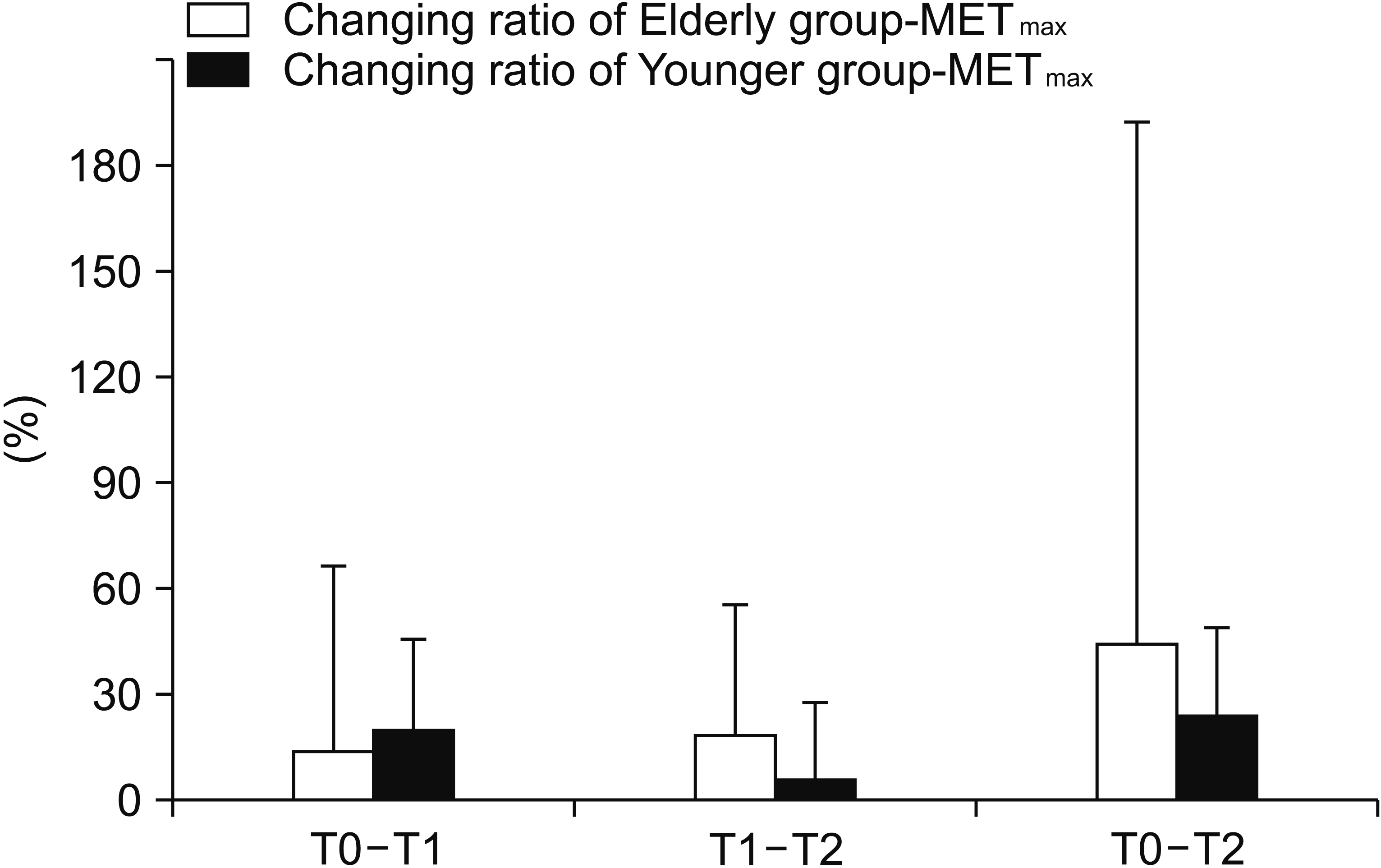

We retrospectively reviewed and analyzed the medical records of patients who were referred to our cardiac rehabilitation (CR) center and underwent percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction (AMI). A total of 70 patients were enrolled who underwent an exercise tolerance test (ETT) 3 weeks after the occurrence of an AMI (T0), 6 weeks after the first ETT (T1), and 12 weeks after the first ETT (T2). Patients older than 65 years were assigned to the elderly group (n=24) and those aged 65 years and younger to the younger group (n=46). Both groups performed center-based or home-based CR for 12 weeks (3 times per week and 1 session per day). Exercise intensity for each individual was based on the target heart rate calculated by the Karvonen formula. The change in maximal metabolic equivalents (METmax) of the two groups was measured at each assessment point (T0, T1, and T2) to investigate the recovery of exercise capacity.

Results

The younger group showed improvement in METmax between T0 and T1. However, METmax of the elderly group showed no significant improvement between T0 and T1. The exercise capacity, measured with METmax, of all groups showed improvement between T0 and T2.

Conclusion

Elderly patients with AMI need a longer duration of CR (>6 weeks) than younger patients with AMI.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Community-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation Conducted in a Public Health Center in South Korea: A Preliminary Study

Sora Baek, Yuncheol Ha, Jaemin Mok, Hee-won Park, Hyo-Rim Son, Mi-Suk Jin

Ann Rehabil Med. 2020;44(6):481-492. doi: 10.5535/arm.20084.

Reference

-

1. McConnell TR, Laubach CA 3rd, Szmedra L. Age and gender related trends in body composition, lipids, and exercise capacity during cardiac rehabilitation. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 1997; 6:37–45.2. Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Littman AB. Benefits of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training in secondary coronary prevention in the elderly. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993; 22:678–83.

Article3. Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD, Rees K, Martin N, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 67:1–12.4. Lavie CJ, Milani RV. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation programs on exercise capacity, coronary risk factors, behavioral characteristics, and quality of life in a large elderly cohort. Am J Cardiol. 1995; 76:177–9.5. Strid C, Lingfors H, Fridlund B, Martensson J. Lifestyle changes in coronary heart disease: effects of cardiac rehabilitation programs with focus on intensity, duration and content: a systematic review. Open J Nurs. 2012; 2:420–30.6. Baldasseroni S, Pratesi A, Francini S, Pallante R, Barucci R, Orso F, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation in very old adults: effect of baseline functional capacity on treatment effectiveness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016; 64:1640–5.

Article7. Bartels M, Prince DZ. Acute medical conditions. In : Cifu DX, editor. Braddom’s physical medicine & rehabilitation. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier;2016. p. 571–96.8. Santiago de Araujo Pio C, Marzolini S, Pakosh M, Grace SL. Effect of cardiac rehabilitation dose on mortality and morbidity: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017; 92:1644–59.9. Price KJ, Gordon BA, Bird SR, Benson AC. A review of guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation exercise programmes: Is there an international consensus? Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016; 23:1715–33.

Article10. Vanhees L, Martens M, Beloka S, Stevens A, Avram A, Gaita D. Cardiac rehabilitation: Europe. In : Perk J, editor. Cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation. London: Springer;2007. p. 30–3.11. Kraal JJ, Vromen T, Spee R, Kemps HMC, Peek N. The influence of training characteristics on the effect of exercise training in patients with coronary artery disease: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2017; 245:52–8.

Article12. Lavie CJ, Milani RV. Disparate effects of improving aerobic exercise capacity and quality of life after cardiac rehabilitation in young and elderly coronary patients. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2000; 20:235–40.

Article13. Menezes AR, Lavie CJ, Forman DE, Arena R, Milani RV, Franklin BA. Cardiac rehabilitation in the elderly. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014; 57:152–9.

Article14. Pasquali SK, Alexander KP, Peterson ED. Cardiac rehabilitation in the elderly. Am Heart J. 2001; 142:748–55.

Article15. Cannistra LB, Balady GJ, O’Malley CJ, Weiner DA, Ryan TJ. Comparison of the clinical profile and outcome of women and men in cardiac rehabilitation. Am J Cardiol. 1992; 69:1274–9.

Article16. Anderson L, Sharp GA, Norton RJ, Dalal H, Dean SG, Jolly K, et al. Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017; 6:CD007130.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Cardiac Rehabilitation After Acute Myocardial Infarction Resuscitated From Cardiac Arrest

- Effects of Cardiac Rehabilitation in Patients with Myocardial Infarction

- Effects of Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs (Phase III) on Cardiovascular and Cardiorespiratory Function of the Elderly with Myocardial Infarction

- The Effects of Cardiac Rehabilitation in Patients with ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction

- Can time delay be shortened in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction?: Experience from Korea acute myocardial infarction registry