J Korean Med Sci.

2020 Apr;35(19):e189. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e189.

Revised Triage and Surveillance Protocols for Temporary Emergency Department Closures in Tertiary Hospitals as a Response to COVID-19 Crisis in Daegu Metropolitan City

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- 2Department of Emergency Medicine, College of Medicine, Yeungnam University, Daegu, Korea

- 3Department of Emergency Medicine, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- 4Department of Emergency Medicine, Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital, Daegu, Korea

- 5Department of Emergency Medicine, Daegu Fatima Hospital, Daegu, Korea

- KMID: 2500634

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e189

Abstract

- Background

When an emergency-care patient is diagnosed with an emerging infectious disease, hospitals in Korea may temporarily close their emergency departments (EDs) to prevent nosocomial transmission. Since February 2020, multiple, consecutive ED closures have occurred due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis in Daegu. However, sudden ED closures are in contravention of laws for the provision of emergency medical care that enable the public to avail prompt, appropriate, and 24-hour emergency medical care. Therefore, this study ascertained the vulnerability of the ED at tertiary hospitals in Daegu with regard to the current standards. A revised triage and surveillance protocol has been proposed to tackle the current crisis.

Methods

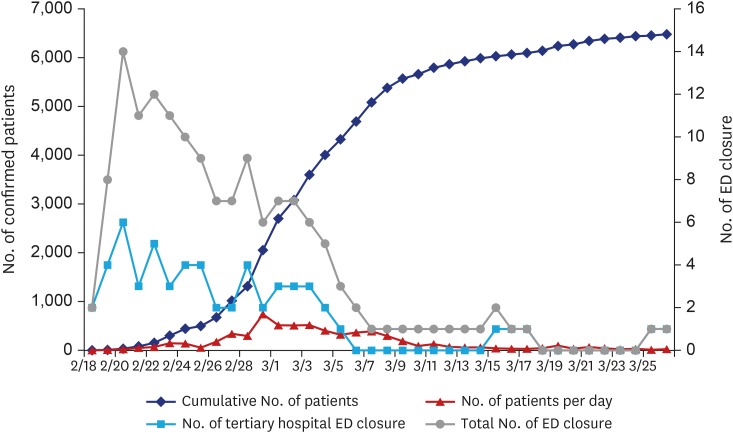

This study was retrospectively conducted at 6 level 1 or 2 EDs in a metropolitan city where ED closure due to COVID-19 occurred from February 18 to March 26, 2020. The present status of ED closure and patient characteristics and findings from chest radiography and laboratory investigations were assessed. Based on the experience from repeated ED closures and the modified systems that are currently used in EDs, revised triage and surveillance protocols have been developed and proposed.

Results

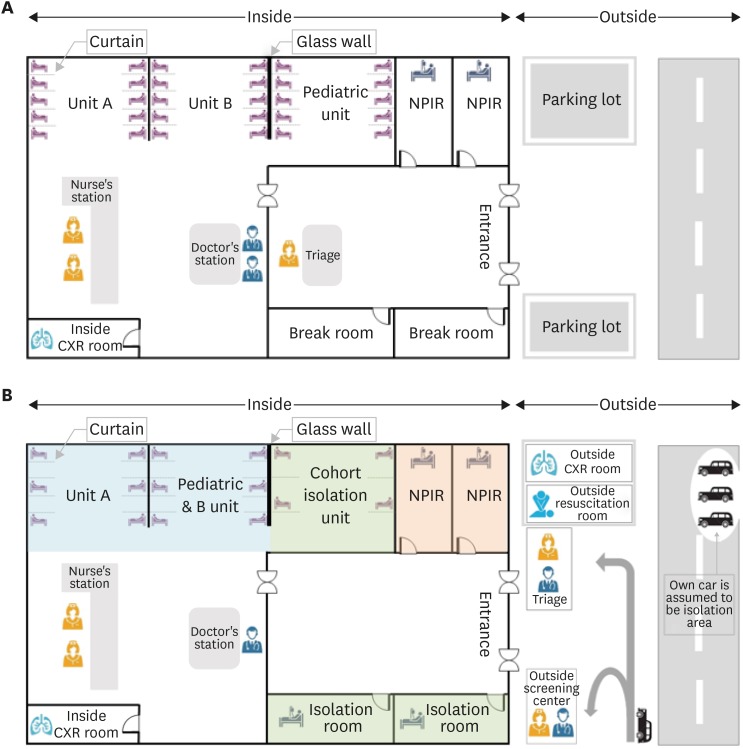

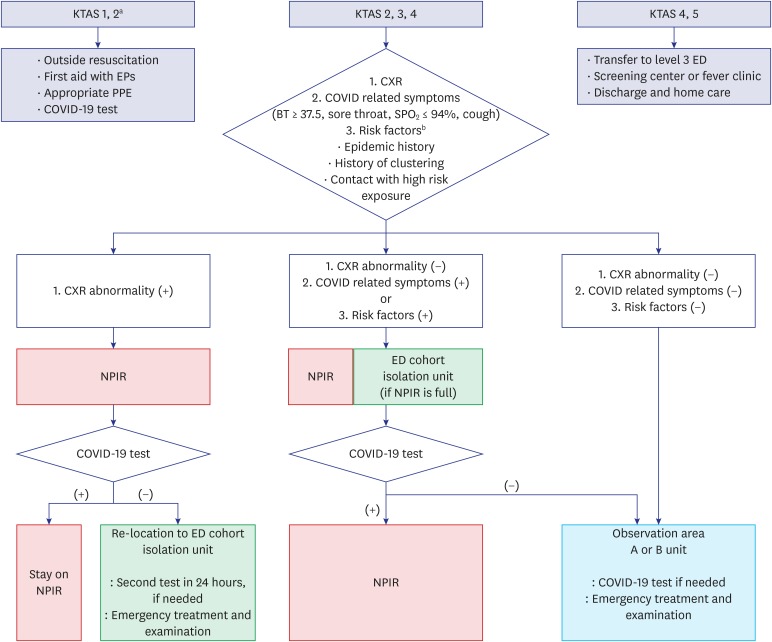

During the study period, 6 level 1 or 2 emergency rooms included in the study were shut down 27 times for 769 hours. Thirty-one confirmed COVID-19 cases, of whom 7 died, were associated with the incidence of ED closure. Typical patient presentation with respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 was seen in less than 50% of patients, whereas abnormal findings on chest imaging investigations were detected in 93.5% of the study population. The chest radiography facility, resuscitation rooms, and triage area were moved to locations outside the ED, and a new surveillance protocol was applied to determine the factors warranting quarantine, including symptoms, chest radiographic findings, and exposure to a source of infection. The incidence of ED closures decreased after the implementation of the revised triage and surveillance protocols.

Conclusion

Triage screening by emergency physicians and surveillance protocols with an externally located chest imaging facility were effective in the early isolation of COVID-19 patients. In future outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases, efforts should be focused toward the provision of continued ED treatment with the implementation of revised triage and surveillance protocols.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

A Systematic Narrative Review of Comprehensive Preparedness Strategies of Healthcare Resources for a Large Resurgence of COVID-19 Nationally, with Local or Regional Epidemics: Present Era and Beyond

Young Kyung Yoon, Jacob Lee, Sang Il Kim, Kyong Ran Peck

J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(44):e387. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e387.Pediatric Emergency Department Utilization and Coronavirus Disease in Daegu, Korea

Kyung Mi Jang, Ji Young Ahn, Hee Joung Choi, Sukhee Lee, Dongsub Kim, Dong Won Lee, Jae Young Choe

J Korean Med Sci. 2020;36(1):e11. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e11.How to Cope with COVID-19 in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Yoo Jin Lee

Korean J Gastroenterol. 2021;77(4):160-163. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2021.403.

Reference

-

1. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreak in the Republic of Korea, 2015. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2015; 6(4):269–278. PMID: 26473095.2. Oh MD, Park WB, Park SW, Choe PG, Bang JH, Song KH, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome: what we learned from the 2015 outbreak in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2018; 33(2):233–246. PMID: 29506344.

Article3. Kang CK, Song KH, Choe PG, Park WB, Bang JH, Kim ES, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of spreaders of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus during the 2015 outbreak in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32(5):744–749. PMID: 28378546.

Article4. Kim JY, Song JY, Yoon YK, Choi SH, Song YG, Kim SR, et al. Middle East Respiratory syndrome infection control and prevention guideline for healthcare facilities. Infect Chemother. 2015; 47(4):278–302. PMID: 26788414.

Article5. National Law Information Center. Emergency medical service act. Updated 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020. http://www.law.go.kr/lsInfoP.do?lsiSeq=215835&efYd=20200324#0000.6. National Emergency Medical Center. Emergency medical statistics yearbook. Updated 2019. Accessed March 28, 2020. https://www.e-gen.or.kr/nemc/statistics_annual_report.do.7. Lee H, Heo JW, Kim SW, Lee J, Choi JH. A lesson from temporary closing of a single university-affiliated hospital owing to in-hospital transmission of coronavirus disease 2019. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(13):e145. PMID: 32242350.

Article8. Yoo JH, Hong ST. The outbreak cases with the novel coronavirus suggest upgraded quarantine and isolation in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(5):e62. PMID: 32030926.

Article9. Zhang J, Zhou L, Yang Y, Peng W, Wang W, Chen X. Therapeutic and triage strategies for 2019 novel coronavirus disease in fever clinics. Lancet Respir Med. 2020; 8(3):e11–2. PMID: 32061335.

Article10. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(18):1708–1720. PMID: 32109013.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- COVID-19 Outbreak in Daegu City, Korea and Response to COVID-19: How Have We Dealt and What Are the Lessons?

- Community-wide Early Response to COVID-19 in Dongnae-gu of Busan City

- The Mass Infection of COVID-19 in Daegu City of Korea: Vascular Surgeons’ Perspective

- Triage-related Challenges Faced by Emergency Nurses during the Peak and Plateau Periods of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Focus Group Study

- A Public-Private Partnership Model to Build a Triage System in Response to a COVID-19 Outbreak in Hanam City, South Korea