J Korean Med Sci.

2020 Apr;35(19):e131. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e131.

Vasospasm-related Sudden Cardiac Death Has Outcomes Comparable with Coronary Stenosis in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Chonnam National University Hospital, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea

- 2Department of Emergency Medicine, Samsung Changwon Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Changwon, Korea

- 3Department of Emergency Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Emergency Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Emergency Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Emergency Medicine, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 7Department of Emergency Medicine, Chung-Ang University, College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 8Department of Emergency Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2500630

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e131

Abstract

- Background

Characteristics of coronary vasospasm-related sudden cardiac death are not well understood. We aimed to compare the characteristics and clinical outcomes between coronary vasospasm and stenosis, in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) survivors, who underwent coronary angiogram (CAG).

Methods

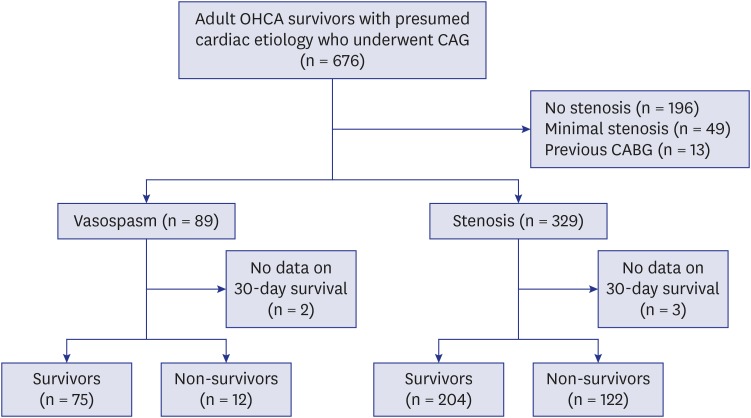

We conducted a multicenter retrospective observational registry-based study at 8 Korean tertiary care centers. Data of OHCA survivors undergoing CAG between 2010 and 2015 were extracted. Patients were divided into vasospasm and stenosis (stenosis > 50%) groups based on CAG findings. The primary and the secondary outcomes were survival and a good neurologic outcome at 30 days after OHCA. Patients in the vasospasm and stenosis groups were propensity score matched.

Results

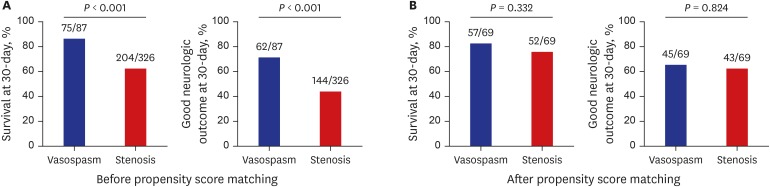

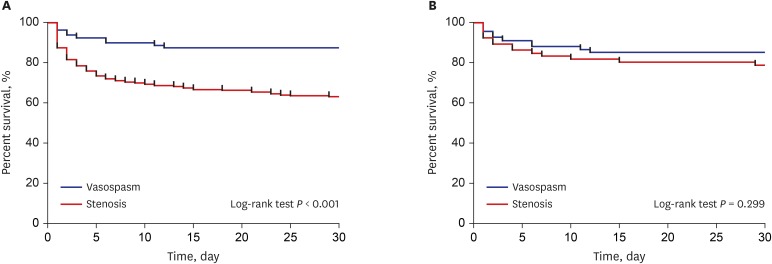

Of the 413 included patients, vasospasm and stenosis groups comprised 87 and 326 patients, respectively. There were 279 (66.7%) survivors and 206 (49.3%) patients with good neurologic outcomes. The vasospasm group had better clinical characteristics for outcome (younger age, less diabetes and hypertension, more prehospital restoration of spontaneous circulation, higher Glasgow Coma Scale, less ST segment elevation, and less requirement of circulatory support). The vasospasm group had better survival (75/87 vs. 204/326, P < 0.001) and good neurologic outcomes (62/87 vs. 144/326, P < 0.001). However, vasospasm was not independently associated with survival (odds ratio [OR], 0.980; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.400–2.406) or neurologic outcomes (OR, 0.870; 95% CI, 0.359–2.108) after adjustment and vasospasm was not associated with survival and neurologic outcome in propensity score-matched cohorts.

Conclusion

Our analysis of propensity score-matched cohorts finds that vasospasm OHCA survivors have survival and neurologic outcomes comparable with those of stenotic OHCA survivors.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Myerberg RJ, Castellanos A. Cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death. In : Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, Braunwald E, editors. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders;2012. p. 845–884.2. Waldmann V, Bougouin W, Karam N, Dumas F, Sharifzadehgan A, Gandjbakhch E, et al. Characteristics and clinical assessment of unexplained sudden cardiac arrest in the real-world setting: focus on idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2018; 39(21):1981–1987. PMID: 29566157.

Article3. Tateishi K, Abe D, Iwama T, Hamabe Y, Aonuma K, Sato A. Clinical value of ST-segment change after return of spontaneous cardiac arrest and emergent coronary angiography in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Diagnostic and therapeutic importance of vasospastic angina. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2018; 7(5):405–413. PMID: 28730843.

Article4. Beltrame JF, Crea F, Kaski JC, Ogawa H, Ong P, Sechtem U, et al. The who, what, why, when, how and where of vasospastic angina. Circ J. 2016; 80(2):289–298. PMID: 26686994.

Article5. Waldmann V, Bougouin W, Karam N, Narayanan K, Sharifzadehgan A, Spaulding C, et al. Coronary vasospasm-related sudden cardiac arrest in the community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72(7):814–815. PMID: 30092958.

Article6. Beltrame JF, Sasayama S, Maseri A. Racial heterogeneity in coronary artery vasomotor reactivity: differences between Japanese and Caucasian patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 33(6):1442–1452. PMID: 10334407.

Article7. El Menyar AA. Drug-induced myocardial infarction secondary to coronary artery spasm in teenagers and young adults. J Postgrad Med. 2006; 52(1):51–56. PMID: 16534169.8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC grand rounds: prescription drug overdoses - a U.S. epidemic. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012; 61(1):10–13. PMID: 22237030.9. Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies--tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370(22):2063–2066. PMID: 24758595.10. Cannon CP, Braunwald E. Unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. In : Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, Braunwald E, editors. Braunwald's Heart Disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders;2012. p. 1178–1209.11. Matsue Y, Suzuki M, Nishizaki M, Hojo R, Hashimoto Y, Sakurada H. Clinical implications of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with vasospastic angina and lethal ventricular arrhythmia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60(10):908–913. PMID: 22840527.

Article12. Da Costa A, Isaaz K, Faure E, Mourot S, Cerisier A, Lamaud M. Clinical characteristics, aetiological factors and long-term prognosis of myocardial infarction with an absolutely normal coronary angiogram; a 3-year follow-up study of 91 patients. Eur Heart J. 2001; 22(16):1459–1465. PMID: 11482919.

Article13. Ahn JM, Lee KH, Yoo SY, Cho YR, Suh J, Shin ES, et al. Prognosis of variant angina manifesting as aborted sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 68(2):137–145. PMID: 27386766.14. Takagi Y, Yasuda S, Tsunoda R, Ogata Y, Seki A, Sumiyoshi T, et al. Clinical characteristics and long-term prognosis of vasospastic angina patients who survived out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: multicenter registry study of the Japanese Coronary Spasm Association. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011; 4(3):295–302. PMID: 21406685.15. Kim YJ, Min SY, Lee DH, Lee BK, Jeung KW, Lee HJ, et al. The role of post-resuscitation electrocardiogram in patients with ST-segment changes in the immediate post-cardiac arrest period. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017; 10(5):451–459. PMID: 28279312.16. Group JC; JCS Joint Working Group. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of patients with vasospastic angina (Coronary Spastic Angina) (JCS 2013). Circ J. 2014; 78(11):2779–2801. PMID: 25273915.

Article17. Booth CM, Boone RH, Tomlinson G, Detsky AS. Is this patient dead, vegetative, or severely neurologically impaired? Assessing outcome for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2004; 291(7):870–879. PMID: 14970067.18. Meune C, Joly LM, Chiche JD, Charpentier J, Leenhardt A, Rozenberg A, et al. Diagnosis and management of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest secondary to coronary artery spasm. Resuscitation. 2003; 58(2):145–152. PMID: 12909376.

Article19. Jansson PA. Endothelial dysfunction in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. J Intern Med. 2007; 262(2):173–183. PMID: 17645585.

Article20. Kugiyama K, Yasue H, Okumura K, Ogawa H, Fujimoto K, Nakao K, et al. Nitric oxide activity is deficient in spasm arteries of patients with coronary spastic angina. Circulation. 1996; 94(3):266–271. PMID: 8759065.

Article21. Li YJ, Hyun MH, Rha SW, Chen KY, Jin Z, Dang Q, et al. Diabetes mellitus is not a risk factor for coronary artery spasm as assessed by an intracoronary acetylcholine provocation test: angiographic and clinical characteristics of 986 patients. J Invasive Cardiol. 2014; 26(6):234–239. PMID: 24907077.22. Ro YS, Shin SD, Song KJ, Kim JY, Lee EJ, Lee YJ, et al. Risk of diabetes mellitus on incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2016; 11(4):e0154245. PMID: 27105059.

Article23. Ro YS, Shin SD, Song KJ, Lee EJ, Lee YJ, Kim JY, et al. Interaction effects between hypothermia and diabetes mellitus on survival outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2015; 90:35–41. PMID: 25725296.

Article24. Hirlekar G, Karlsson T, Aune S, Ravn-Fischer A, Albertsson P, Herlitz J, et al. Survival and neurological outcome in the elderly after in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2017; 118:101–106. PMID: 28736324.

Article25. Lee BK, Lee SJ, Park CH, Jeung KW, Jung YH, Lee DH, et al. Relationship between age and outcomes of comatose cardiac arrest survivors in a setting without withdrawal of life support. Resuscitation. 2017; 115:75–81. PMID: 28392372.

Article26. Kim WY, Giberson TA, Uber A, Berg K, Cocchi MN, Donnino MW. Neurologic outcome in comatose patients resuscitated from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with prolonged downtime and treated with therapeutic hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2014; 85(8):1042–1046. PMID: 24746783.

Article27. Mader TJ, Nathanson BH, Millay S, Coute RA, Clapp M, McNally B, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes stratified by rhythm analysis. Resuscitation. 2012; 83(11):1358–1362. PMID: 22490674.

Article28. Myerburg RJ, Kessler KM, Mallon SM, Cox MM, deMarchena E, Interian A Jr, et al. Life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in patients with silent myocardial ischemia due to coronary-artery spasm. N Engl J Med. 1992; 326(22):1451–1455. PMID: 1574091.

Article29. Kim YT, Shin SD, Hong SO, Ahn KO, Ro YS, Song KJ, et al. Effect of national implementation of utstein recommendation from the global resuscitation alliance on ten steps to improve outcomes from Out-of-Hospital cardiac arrest: a ten-year observational study in Korea. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(8):e016925.

Article30. Yasue H, Takizawa A, Nagao M, Nishida S, Horie M, Kubota J, et al. Long-term prognosis for patients with variant angina and influential factors. Circulation. 1988; 78(1):1–9. PMID: 3260150.

Article31. Bro-Jeppesen J, Annborn M, Hassager C, Wise MP, Pelosi P, Nielsen N, et al. Hemodynamics and vasopressor support during targeted temperature management at 33°C Versus 36°C after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a post hoc study of the target temperature management trial. Crit Care Med. 2015; 43(2):318–327. PMID: 25365723.32. Bruschke AV, Proudfit WL, Sones FM Jr. Progress study of 590 consecutive nonsurgical cases of coronary disease followed 5-9 years. I. Arterographic correlations. Circulation. 1973; 47(6):1147–1153. PMID: 4709534.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Aborted Sudden Cardiac Death during Exercise Associated with an Anomalous Origin of Right Coronary Artery

- Can documented coronary vasospasm be the smoking gun in settling the etiology of sudden cardiac death?

- Medullary Infarction Presenting as Sudden Cardiac Arrest: Report of Two Cases and Review of the Literature

- A Case of Successful Recovery from High Dose Intravenous Nicorandil Infusion in Refractory Coronary Vasospasm with Hemodynamic Collapse

- Recurrent Cardiac Arrest during a Nontransplant Operation Due to Variant Angina in a Liver Transplantation Patient