Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol.

2020 May;13(2):123-132. 10.21053/ceo.2019.00780.

Vestibulocochlear Symptoms Caused by Vertebrobasilar Dolichoectasia

- Affiliations

-

- 1Departments of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 2Departments of Radiology, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 3Department of Radiology, Ajou University Hospital, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea

- 4Dizziness Center, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- KMID: 2500284

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.21053/ceo.2019.00780

Abstract

Objectives

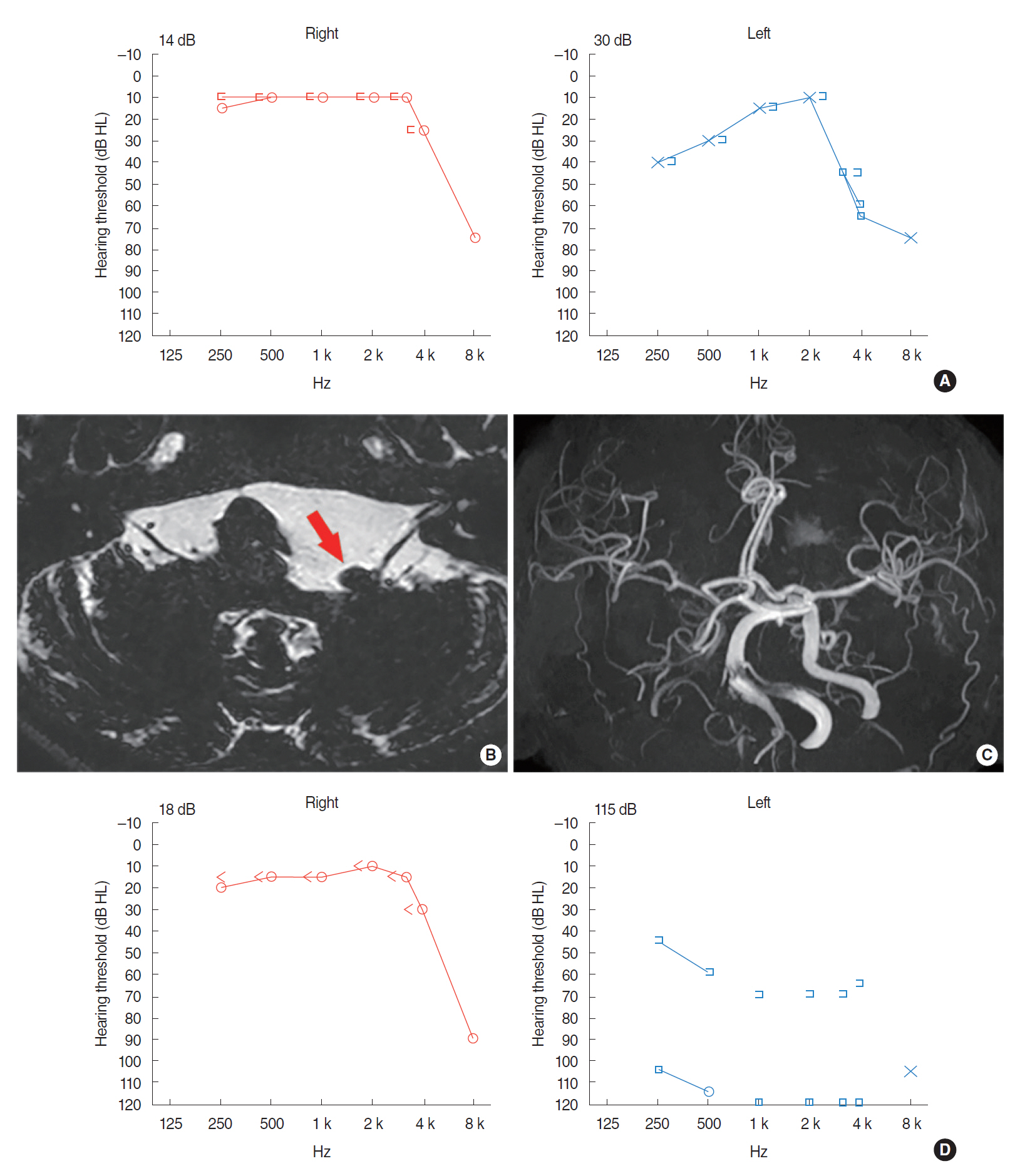

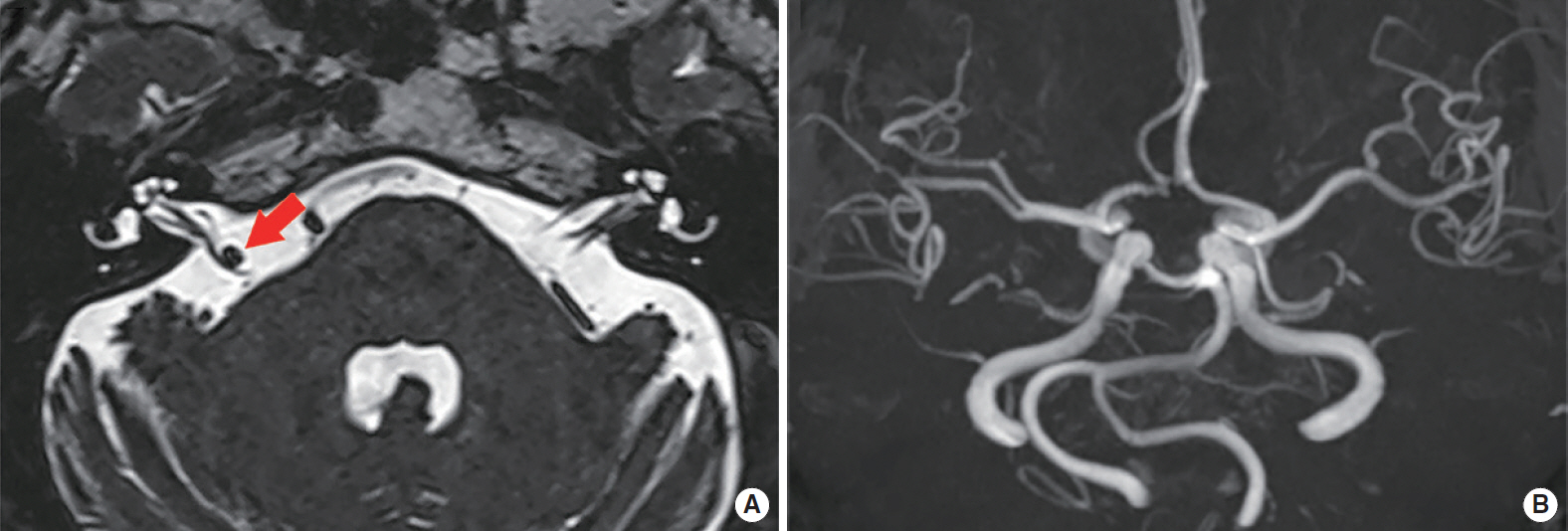

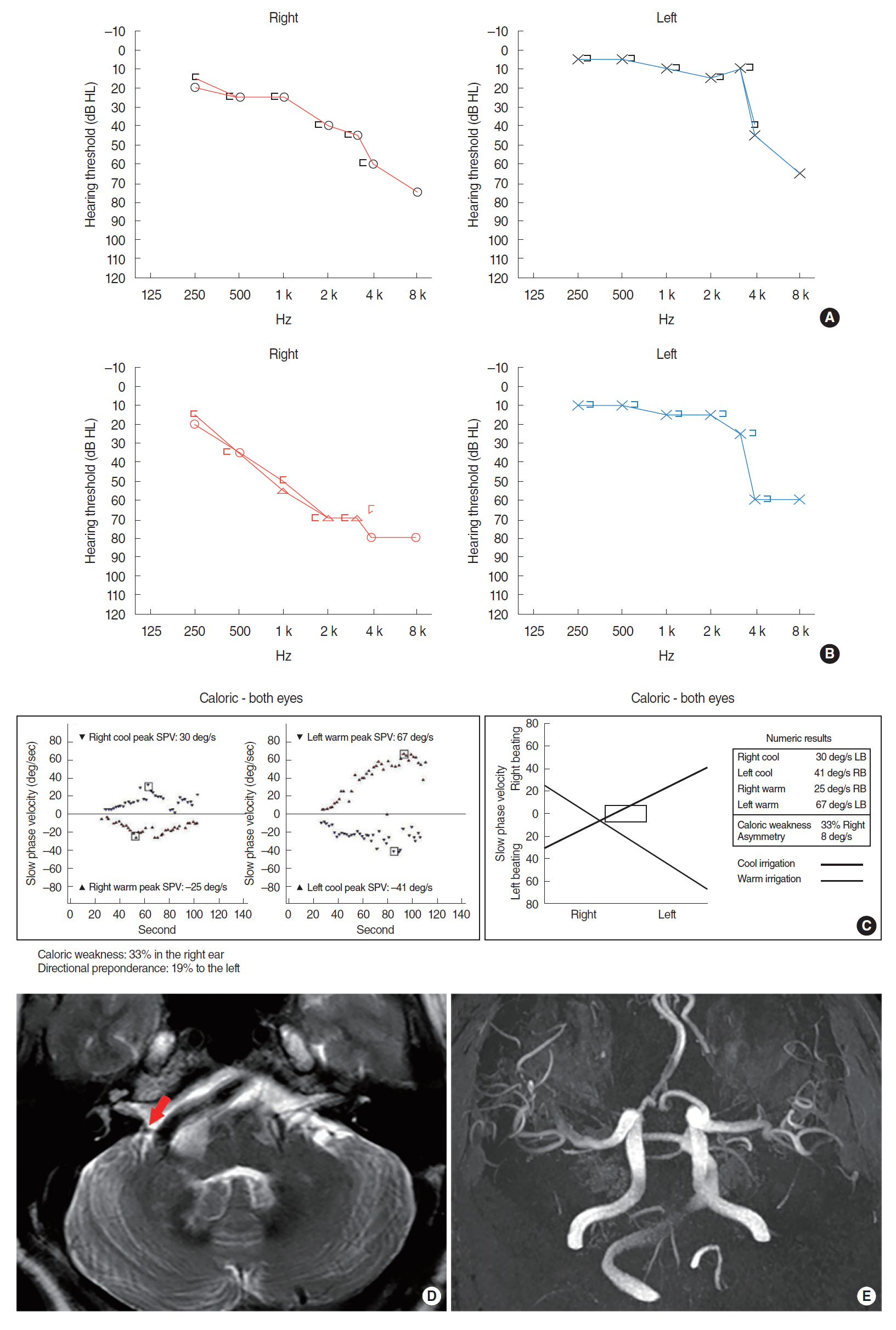

. Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia (VBD), an elongation and distension of vertebrobasilar artery, may present with cranial nerve symptoms due to nerve root compression. The objectives of this study are to summarize vestibulocochlear manifestations in subjects with VBD through a case series and to discuss the needs of thorough oto-neurotologic evaluation in VBD subjects before selecting treatment modalities.

Methods

. Four VBD subjects with vestibulocochlear manifestations were reviewed retrospectively. VBD was confirmed by either brain or internal auditory canal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). Patient information, medical history, MRI/MRA findings, and audiometry or vestibular function tests were reviewed according to patient’s specific symptom.

Results

. Of the four subjects, three presented with ipsilesional sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), three with paroxysmal recurrent vertigo, and two with typewriter tinnitus. The MRI/MRA of the four subjects revealed unilateral VBD with neurovascular compression of cisternal segment or the brainstem causing displacement, angulation, or deformity of the cranial nerve VII or VIII that corresponded to the symptoms.

Conclusion

. Vestibulocochlear symptoms such as SNHL, recurrent paroxysmal vertigo, or typewriter tinnitus can be precipitated from a neurovascular compression of the vestibulocochlear nerve by VBD. Because proper medical or surgical treatments may stop the disease progression or improve audio-vestibular symptoms in subjects with VBD, a high index of suspicion and meticulous radiologic evaluation are needed when vestibulocochlear symptoms are not otherwise explainable, and if VBD is confirmed to cause audiovestibular manifestation, a thorough oto-neurotologic evaluation should be performed before initial treatment.

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Increased Risk of Psychopathological Abnormalities in Subjects With Unilateral Hearing Loss: A Cross-Sectional Study

Jae-Jin Song, Eu Jeong Ku, Seoyoung Kim, Euitae Kim, Young-Seok Choi, Hahn Jin Jung

Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;14(1):82-87. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2020.00283.Earmold Foreign Bodies in the Middle Ear Necessitating Surgical Removal: Why Otology Specialists Should Screen Candidates for Hearing Aids

Sung-Dong Cho, Jeong Hun Jang, Hantai Kim, Yang-Sun Cho, Yoonjoong Kim, Ja-Won Koo, Jae-Jin Song

Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;14(2):235-239. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2020.00850.

Reference

-

1. Wolters FJ, Rinkel GJ, Vergouwen MD. Clinical course and treatment of vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia: a systematic review of the literature. Neurol Res. 2013; Mar. 35(2):131–7.

Article2. Lou M, Caplan LR. Vertebrobasilar dilatative arteriopathy (dolichoectasia). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010; Jan. 1184(1):121–33.

Article3. Ikeda K, Nakamura Y, Hirayama T, Sekine T, Nagata R, Kano O, et al. Cardiovascular risk and neuroradiological profiles in asymptomatic vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010; Jun. 30(1):23–8.

Article4. Smoker WR, Price MJ, Keyes WD, Corbett JJ, Gentry LR. High-resolution computed tomography of the basilar artery: 1. normal size and position. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1986; Jan-Feb. 7(1):55–60.5. Ubogu EE, Zaidat OO. Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia diagnosed by magnetic resonance angiography and risk of stroke and death: a cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004; Jan. 75(1):22–6.6. Passero SG, Rossi S. Natural history of vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. Neurology. 2008; Jan. 70(1):66–72.

Article7. El-Ghandour NM. Microvascular decompression in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia caused by vertebrobasilar ectasia. Neurosurgery. 2010; Aug. 67(2):330–7.

Article8. Gilbow RC, Ruhl DS, Hashisaki GT. Unilateral sensorineural hearing loss associated with vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. Otol Neurotol. 2018; Jan. 39(1):e56–7.

Article9. Samim M, Goldstein A, Schindler J, Johnson MH. Multimodality imaging of vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia: clinical presentations and imaging spectrum. Radiographics. 2016; Jul-Aug. 36(4):1129–46.

Article10. Smoker WR, Corbett JJ, Gentry LR, Keyes WD, Price MJ, McKusker S. High-resolution computed tomography of the basilar artery: 2. vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia: clinical-pathologic correlation and review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1986; Jan-Feb. 7(1):61–72.11. Lee SY, Nam DW, Koo JW, De Ridder D, Vanneste S, Song JJ. No auditory experience, no tinnitus: lessons from subjects with congenital- and acquired single-sided deafness. Hear Res. 2017; Oct. 354:9–15.12. Jeon HW, Kim SY, Choi BS, Bae YJ, Koo JW, Song JJ. Pseudo-low frequency hearing loss and its improvement after treatment may be objective signs of significant vascular pathology in patients with pulsatile tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2016; Oct. 37(9):1344–9.

Article13. Kim CS, Kim SY, Choi H, Koo JW, Yoo SY, An GS, et al. Transmastoid reshaping of the sigmoid sinus: preliminary study of a novel surgical method to quiet pulsatile tinnitus of an unrecognized vascular origin. J Neurosurg. 2016; Aug. 125(2):441–9.

Article14. Song JJ, Hong SK, Lee SY, Park SJ, Kang SI, An YH, et al. Vestibular manifestations in subjects with enlarged vestibular aqueduct. Otol Neurotol. 2018; Jul. 39(6):e461–7.

Article15. Bae YJ, Song JJ, Choi BS, Kang Y, Kim JH, Koo JW. Differentiation between intralabyrinthine schwannoma and contrast-enhancing labyrinthitis on MRI: quantitative analysis of signal intensity characteristics. Otol Neurotol. 2018; Sep. 39(8):1045–52.

Article16. Shim YJ, Bae YJ, An GS, Lee K, Kim Y, Lee SY, et al. Involvement of the internal auditory canal in subjects with cochlear otosclerosis: a less acknowledged third window that affects surgical outcome. Otol Neurotol. 2019; Mar. 40(3):e186–90.

Article17. He X, Duan C, Zhang J, Li X, Zhang X, Li Z. The safety and efficacy of using large woven stents to treat vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019; Jun. 13. [Epub]. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-014933.

Article18. Passero S, Nuti D. Auditory and vestibular system findings in patients with vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. Acta Neurol Scand. 1996; Jan. 93(1):50–5.

Article19. Titlic M, Tonkic A, Jukic I, Buca A, Kolic K, Batinic T. Tinnitus caused by vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2007; 108(10-11):455–7.20. Jacobson DM, Corbett JJ. Downbeat nystagmus and dolichoectasia of the vertebrobasilar artery. J Neuroophthalmol. 2002; Jun. 22(2):150–1.

Article21. Czyz CN, Burns JA, Petrie TP, Watkins JR, Cahill KV, Foster JA. Long-term botulinum toxin treatment of benign essential blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm, and Meige syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013; Jul. 156(1):173–7.

Article22. Wang X, Thirumala PD, Shah A, Gardner P, Habeych M, Crammond DJ, et al. Effect of previous botulinum neurotoxin treatment on microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. Neurosurg Focus. 2013; Mar. 34(3):E3.

Article23. Savitz SI, Ronthal M, Caplan LR. Vertebral artery compression of the medulla. Arch Neurol. 2006; Feb. 63(2):234–41.

Article24. Sun S, Jiang W, Wang J, Gao P, Zhang X, Jiao L, et al. Clinical analysis and surgical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia caused by vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia: a retrospective study. Int J Surg. 2017; May. 41:183–9.

Article25. Barker FG 2nd, Jannetta PJ, Bissonette DJ, Larkins MV, Jho HD. The long-term outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 1996; Apr. 334(17):1077–83.

Article26. Sunwoo W, Jeon YJ, Bae YJ, Jang JH, Koo JW, Song JJ. Typewriter tinnitus revisited: the typical symptoms and the initial response to carbamazepine are the most reliable diagnostic clues. Sci Rep. 2017; Sep. 7(1):10615.

Article27. Bae YJ, Jeon YJ, Choi BS, Koo JW, Song JJ. The role of MRI in diagnosing neurovascular compression of the cochlear nerve resulting in typewriter tinnitus. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017; Jun. 38(6):1212–7.

Article28. Mardini MK. Ear-clicking “tinnitus” responding to carbamazepine. N Engl J Med. 1987; Dec. 317(24):1542.

Article29. Hufner K, Barresi D, Glaser M, Linn J, Adrion C, Mansmann U, et al. Vestibular paroxysmia: diagnostic features and medical treatment. Neurology. 2008; Sep. 71(13):1006–14.

Article30. Mazzoni A. Internal auditory artery supply to the petrous bone. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1972; Feb. 81(1):13–21.

Article31. Han SA, Choe G, Kim Y, Koo JW, Choi BY, Song JJ. Beware of a fragile footplate: lessons from ossiculoplasty in patients with ossicular anomalies related to second pharyngeal arch defects. J Clin Med. 2019; Dec. 8(12):2130.

Article32. Bae YJ, Shim YJ, Choi BS, Kim JH, Koo JW, Song JJ. “Third window” and “single window” effects impede surgical success: analysis of retrofenestral otosclerosis involving the internal auditory canal or round window. J Clin Med. 2019; Aug. 8(8):1182.

Article33. Han J, De Ridder D, Vanneste S, Chen YC, Koo JW, Song JJ. Pre-treatment ongoing cortical oscillatory activity predicts improvement of tinnitus after partial peripheral reafferentation with hearing aids. Front Neurosci. 2020; 14:410.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A case of vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia manifesting as sudden sensorineural hearing loss with vertigo

- One Case of Downbeat Nystagmus with Compression of Vestibulocochlear Nerve by Vertebral Arteries

- Huge Vertebrobasilar Dolichoectasia

- Lower Cranial Nerve Palsy Due to Vertebrobasilar Dolichoectasia

- Vestibular Function Test in Old Age Patients with Vertebrobasilar Dolichoectasia