Korean Circ J.

2020 May;50(5):406-417. 10.4070/kcj.2019.0319.

Comparison of Exercise Performance and Clinical Outcome Between Functional Complete and Incomplete Revascularization

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Heart Vascular Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. drone80@hanmail.net, sh1214.choi@samsung.com

- 2Cardiovascular Imaging Center, Heart Vascular Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Cardiac Rehabilitation and Prevention Center, Heart Vascular Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiovascular Center, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2471779

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2019.0319

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Although percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is recommended to improve symptoms in patients with stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD), improvement of exercise performance is controversial. This study aimed to investigate changes in exercise duration after PCI according to functional completeness of revascularization by comparing pre- and post-PCI exercise stress test (EST).

METHODS

Patients with SIHD were enrolled from a prospective PCI registry, and divided into 2 groups: 1) functional complete revascularization (CR) group had a positive EST before PCI and negative EST after PCI, 2) functional incomplete revascularization (IR) group had positive EST before and after PCI. Primary outcome was change in exercise duration after PCI and secondary outcome was major adverse cardiac events (MACE, a composite of any death, any myocardial infarction, and any ischemia-driven revascularization) at 3 years after PCI.

RESULTS

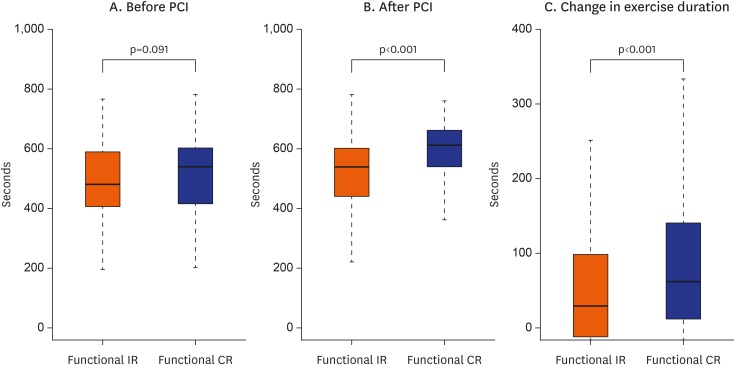

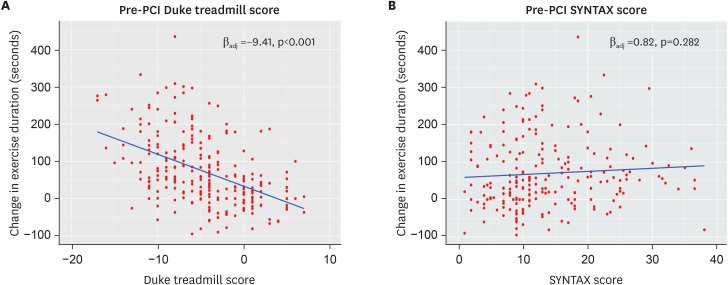

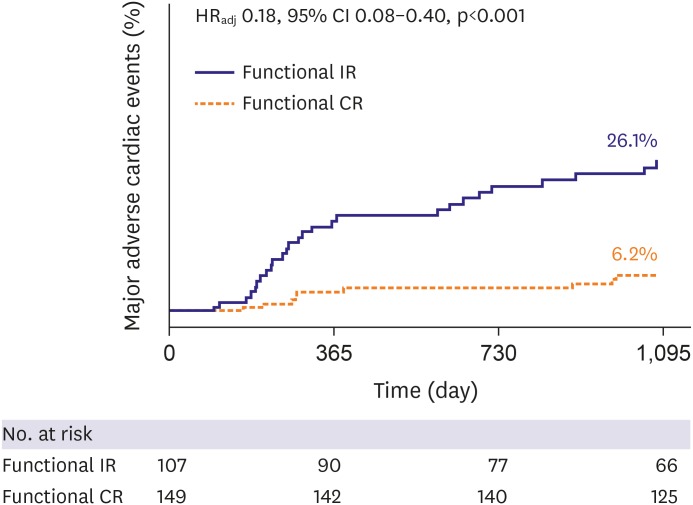

A total of 256 patients (149 for CR group, and 107 for IR group) were eligible for analysis. Before PCI, exercise duration was not significantly different between the functional CR and IR groups (median 540 [interquartile range; IQR, 414, 602] vs. 480 [402, 589] seconds, p=0.091). After PCI, however, the CR group had a significantly higher increment of exercise duration than the IR group (median 62.0 [IQR, 12.0, 141.0] vs. 30.0 [−11.0, 103.5] seconds, p=0.011). The functional CR group also had a significantly lower risk of 3-year MACE (6.2% vs. 26.1%; adjusted hazard ratio, 0.19; 95% confidence interval, 0.09-0.41; p<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

Functional CR showed a higher increment of exercise duration than functional IR.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Weintraub WS, Spertus JA, Kolm P, et al. Effect of PCI on quality of life in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:677–687. PMID: 18703470.2. Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, Do D, Partington S, Atwood JE. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:793–801. PMID: 11893790.3. Hung RK, Al-Mallah MH, McEvoy JW, et al. Prognostic value of exercise capacity in patients with coronary artery disease: the FIT (Henry Ford ExercIse Testing) project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014; 89:1644–1654. PMID: 25440889.4. Parisi AF, Folland ED, Hartigan P. A comparison of angioplasty with medical therapy in the treatment of single-vessel coronary artery disease. Veterans affairs ACME investigators. N Engl J Med. 1992; 326:10–16. PMID: 1345754.5. Hambrecht R, Walther C, Möbius-Winkler S, et al. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty compared with exercise training in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2004; 109:1371–1378. PMID: 15007010.6. Al-Lamee R, Thompson D, Dehbi HM, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018; 391:31–40. PMID: 29103656.7. Fletcher GF, Ades PA, Kligfield P, et al. Exercise standards for testing and training: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013; 128:873–934. PMID: 23877260.8. Mark DB, Shaw L, Harrell FE Jr, et al. Prognostic value of a treadmill exercise score in outpatients with suspected coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:849–853. PMID: 1875969.9. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:2551–2567. PMID: 22922414.10. Choi BC, Pak AW. A catalog of biases in questionnaires. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005; 2:A13.11. Guazzi M, Bandera F, Ozemek C, Systrom D, Arena R. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing: what is its value? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 70:1618–1636. PMID: 28935040.12. Gehi AK, Ali S, Na B, Schiller NB, Whooley MA. Inducible ischemia and the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events in outpatients with stable coronary heart disease: the heart and soul study. Arch Intern Med. 2008; 168:1423–1428. PMID: 18625923.13. Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008; 117:1283–1291. PMID: 18268144.14. Hachamovitch R, Rozanski A, Shaw LJ, et al. Impact of ischaemia and scar on the therapeutic benefit derived from myocardial revascularization vs. medical therapy among patients undergoing stress-rest myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:1012–1024. PMID: 21258084.15. Tonino PA, Fearon WF, De Bruyne B, et al. Angiographic versus functional severity of coronary artery stenoses in the FAME study fractional flow reserve versus angiography in multivessel evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:2816–2821. PMID: 20579537.16. Lele SS, Macfarlane D, Morrison S, Thomson H, Khafagi F, Frenneaux M. Determinants of exercise capacity in patients with coronary artery disease and mild to moderate systolic dysfunction. Role of heart rate and diastolic filling abnormalities. Eur Heart J. 1996; 17:204–212. PMID: 8732373.17. Tajima A, Itoh H, Osada N, et al. Oxygen uptake kinetics during and after exercise are useful markers of coronary artery disease in patients with exercise electrocardiography suggesting myocardial ischemia. Circ J. 2009; 73:1864–1870. PMID: 19661720.18. Belardinelli R, Lacalaprice F, Carle F, et al. Exercise-induced myocardial ischaemia detected by cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Eur Heart J. 2003; 24:1304–1313. PMID: 12871687.19. Al-Lamee R, Howard JP, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Fractional flow reserve and instantaneous wave-free ratio as predictors of the placebo-controlled response to percutaneous coronary intervention in stable single-vessel coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2018; 138:1780–1792. PMID: 29789302.20. Choi KH, Lee JM, Koo BK, et al. Prognostic implication of functional incomplete revascularization and residual functional SYNTAX score in patients with coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018; 11:237–245. PMID: 29361444.21. Xaplanteris P, Fournier S, Pijls NH, et al. Five-year outcomes with PCI guided by fractional flow reserve. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:250–259. PMID: 29785878.22. Hendel RC, Berman DS, Di Carli MF, et al. ACCF/ASNC/ACR/AHA/ASE/SCCT/SCMR/SNM 2009 appropriate use criteria for cardiac radionuclide imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Circulation. 2009; 119:e561–87. PMID: 19451357.23. Nissen SE, Tardif JC, Nicholls SJ, et al. Effect of torcetrapib on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:1304–1316. PMID: 17387129.24. Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Libby P, et al. Effect of antihypertensive agents on cardiovascular events in patients with coronary disease and normal blood pressure: the CAMELOT study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004; 292:2217–2225. PMID: 15536108.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effects of Low-intensity Exercise on Functional Ability in Hospitalized Elderly

- Ischemia-guided Revascularization for Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

- Effects of Therapeutic Exercise on Patients with Osteoarthritis of Knee

- Impact of Complete Revascularization for Acute Myocardial Infarction In Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease Patients With Diabetes Mellitus

- The Effect of Strengthening Exercise Program on the Physical Activity, Activities of Daily Living, Social Behavior and Functional Performance of the Elderly in a Home for the Aged