J Korean Med Sci.

2016 Nov;31(11):1797-1801. 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1797.

Seasonal Pattern of Preterm Births in Korea for 2000–2012

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Korea University Guro Hospital, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. md_cho@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2470277

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1797

Abstract

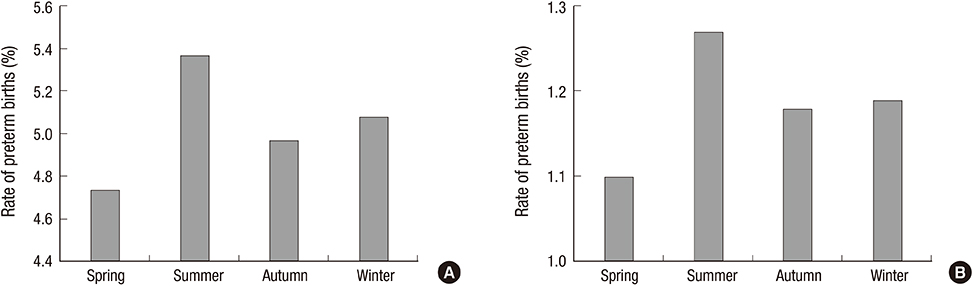

- The aim of this study was to investigate a seasonal pattern of preterm births in Korea. Data were obtained from the national birth registry of the Korean Statistics Office and included all births in Korea during the period 2000-2012 (n = 6,310,800). Delivery dates were grouped by month of the year or by season (winter [December, January, February], spring [March, April, May], summer [June, July, August], and autumn [September, October, November]). The seasonal patterns of prevalence of preterm births were assessed. The rates of preterm births at 37 weeks were highest twice a year (once in winter and again in summer). The rates of preterm births increased by 13.9% in summer and 7.5% in winter, respectively, than in spring (OR, 1.139; 95% CI, 1.127-1.152, and OR, 1.075; 95% 1.064-1.087, respectively) after controlling for age, the educational level of the parents, maternal parity, and neonatal gender. The pattern for spontaneous preterm births < 34 weeks was similar. In Korea, a seasonal pattern of preterm births was observed, with peak prevalence in summer and winter. A seasonal pattern of preterm births may provide new insights for the pathophysiology of preterm births.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Wang ML, Dorer DJ, Fleming MP, Catlin EA. Clinical outcomes of near-term infants. Pediatrics. 2004; 114:372–376.2. Kelleher MO, Murray DJ, McGillivary A, Kamel MH, Allcutt D, Earley MJ. Behavioral, developmental, and educational problems in children with nonsyndromic trigonocephaly. J Neurosurg. 2006; 105:382–384.3. Lim JW, Chung SH, Kang DR, Kim CR. Risk factors for cause-specific mortality of very-low-birth-weight infants in the Korean neonatal network. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30:Suppl 1. S35–44.4. Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, Betran AP, Merialdi M, Requejo JH, Rubens C, Menon R, Van Look PF. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull World Health Organ. 2010; 88:31–38.5. Bhutta AT, Cleves MA, Casey PH, Cradock MM, Anand KJ. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002; 288:728–737.6. Farooqi A, Hägglöf B, Sedin G, Gothefors L, Serenius F. Growth in 10- to 12-year-old children born at 23 to 25 weeks’ gestation in the 1990s: a Swedish national prospective follow-up study. Pediatrics. 2006; 118:e1452–65.7. Farooqi A, Hägglöf B, Sedin G, Gothefors L, Serenius F. Chronic conditions, functional limitations, and special health care needs in 10- to 12-year-old children born at 23 to 25 weeks’ gestation in the 1990s: a Swedish national prospective follow-up study. Pediatrics. 2006; 118:e1466–77.8. Marlow N. Neurocognitive outcome after very preterm birth. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004; 89:F224–8.9. Hille ET, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, Jacobusse GW, Ens-Dokkum MH, de Groot L, Wit JM, Geven WB, Kok JH, de Kleine MJ, et al. Functional outcomes and participation in young adulthood for very preterm and very low birth weight infants: the Dutch project on preterm and small for gestational age infants at 19 years of age. Pediatrics. 2007; 120:e587–95.10. Petrou S. The economic consequences of preterm birth during the first 10 years of life. BJOG. 2005; 112:Suppl 1. 10–15.11. Petrou S, Mehta Z, Hockley C, Cook-Mozaffari P, Henderson J, Goldacre M. The impact of preterm birth on hospital inpatient admissions and costs during the first 5 years of life. Pediatrics. 2003; 112:1290–1297.12. Strand LB, Barnett AG, Tong S. The influence of season and ambient temperature on birth outcomes: a review of the epidemiological literature. Environ Res. 2011; 111:451–462.13. Lim JW, Lee JJ, Park CG, Sriram S, Lee KS. Birth outcomes of Koreans by birthplace of infants and their mothers, the United States versus Korea, 1995-2004. J Korean Med Sci. 2010; 25:1343–1351.14. Lee SS, Kwon HS, Choi HM. Evaluation of preterm delivery between 32-33 weeks of gestation. J Korean Med Sci. 2008; 23:964–968.15. Romero R, Mazor M, Munoz H, Gomez R, Galasso M, Sherer DM. The preterm labor syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994; 734:414–429.16. Hewitt D. A study of temporal variations in the risk of fetal malformation and death. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1962; 52:1676–1688.17. Cooperstock M, Wolfe RA. Seasonality of preterm birth in the collaborative perinatal project: demographic factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1986; 124:234–241.18. Bodnar LM, Simhan HN. The prevalence of preterm birth and season of conception. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008; 22:538–545.19. Matsuda S, Kahyo H. Seasonality of preterm births in Japan. Int J Epidemiol. 1992; 21:91–100.20. Keller CA, Nugent RP. Seasonal patterns in perinatal mortality and preterm delivery. Am J Epidemiol. 1983; 118:689–698.21. Lee SJ, Steer PJ, Filippi V. Seasonal patterns and preterm birth: a systematic review of the literature and an analysis in a London-based cohort. BJOG. 2006; 113:1280–1288.22. Flouris AD, Spiropoulos Y, Sakellariou GJ, Koutedakis Y. Effect of seasonal programming on fetal development and longevity: links with environmental temperature. Am J Hum Biol. 2009; 21:214–216.23. Yackerson N, Piura B, Sheiner E. The influence of meteorological factors on the emergence of preterm delivery and preterm premature rupture of membrane. J Perinatol. 2008; 28:707–711.24. Basu R, Malig B, Ostro B. High ambient temperature and the risk of preterm delivery. Am J Epidemiol. 2010; 172:1108–1117.25. Lee SE, Park IS, Romero R, Yoon BH. Amniotic fluid prostaglandin F2 increases even in sterile amniotic fluid and is an independent predictor of impending delivery in preterm premature rupture of membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009; 22:880–886.26. Kelly AJ, Malik S, Smith L, Kavanagh J, Thomas J. Vaginal prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGF2a) for induction of labour at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; CD003101.27. Stan CM, Boulvain M, Pfister R, Hirsbrunner-Almagbaly P. Hydration for treatment of preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; CD003096.28. Murray LJ, O’Reilly DP, Betts N, Patterson CC, Davey Smith G, Evans AE. Season and outdoor ambient temperature: effects on birth weight. Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 96:689–695.29. Elter K, Ay E, Uyar E, Kavak ZN. Exposure to low outdoor temperature in the midtrimester is associated with low birth weight. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004; 44:553–557.30. Leem JH, Kaplan BM, Shim YK, Pohl HR, Gotway CA, Bullard SM, Rogers JF, Smith MM, Tylenda CA. Exposures to air pollutants during pregnancy and preterm delivery. Environ Health Perspect. 2006; 114:905–910.31. Backes CH, Nelin T, Gorr MW, Wold LE. Early life exposure to air pollution: how bad is it? Toxicol Lett. 2013; 216:47–53.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Changing Seasonal Pattern of Suicides in Korea Between 2000 and 2019

- Comparison of Respiratory Morbidity in Late Preterm and Term Infants at a Single Institution

- Births to Parents with Asian Origins in the United States, 1992–2012

- Seasonal Variation of Pre-term Births in Korea

- Recent Trends in the Incidence of Multiple Births and Its Consequences on Perinatal Problems in Korea