J Korean Med Assoc.

2020 Feb;63(2):96-104. 10.5124/jkma.2020.63.2.96.

Comparison of the risks of combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and heated tobacco products

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Family Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. hjcho@amc.seoul.kr

- KMID: 2470064

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2020.63.2.96

Abstract

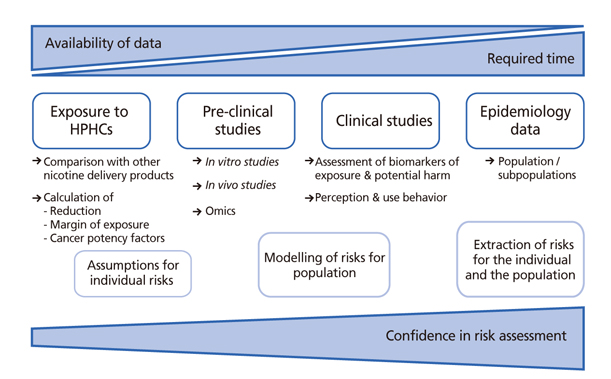

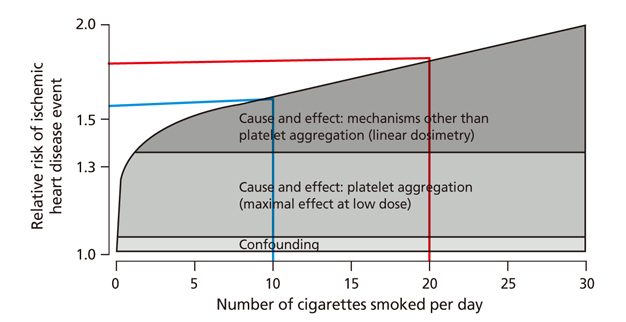

- E-cigarettes (ECs) and heated tobacco products (HTPs) have become popular in Korea; hence, it is important to determine whether ECs and HTPs are less hazardous than combustible cigarettes (CCs). In general, the levels of harmful and potentially harmful constituents (HPHCs) are lower in ECs and HTPs than in CCs, although the levels of some heavy metals and HPHCs are higher in ECs and HTPs than in CCs. ECs and HTPs showed possible adverse effects on respiratory and cardiovascular system function, which could result in chronic respiratory and cardiovascular system diseases in animals. An analysis of biomarkers showed that ECs had possible adverse health effects on the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, in addition the effects of HTP on respiratory and cardiovascular systems were not significantly different than those of CC. Epidemiological studies identified positive associations between EC use and asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and myocardial infarction. Only one epidemiologic study reported a positive association between ever using HTPs and asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis among adolescents. Modelling studies of ECs did not show consistent findings regarding the health effects compared with those of CCs. A modeling study of HTPs, performed by tobacco industry, has been criticized for many unfounded assumptions. Lower levels of HPHCs in ECs and HTPs, compared with those in CCs, cannot be directly translated into health benefits because the relationship between exposure and effects is non-linear for cardiovascular diseases and because the duration of exposure is more important than the level of exposure in determining lung cancer mortality. In summary, there is no definite health benefit in using ECs or HTPs instead of CCs, for the individual or the population; hence, tobacco control measures should be the same for ECs, HTPs, and CCs. ECs and HTPs have become popular in Korea; hence, it is important to determine whether ECs and HTPs are less hazardous than CCs.

MeSH Terms

-

Adolescent

Animals

Asthma

Biomarkers

Cardiovascular Diseases

Cardiovascular System

Dermatitis, Atopic

Electronic Cigarettes*

Epidemiologic Studies

Hot Temperature*

Humans

Insurance Benefits

Korea

Lung Neoplasms

Metals, Heavy

Mortality

Myocardial Infarction

Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive

Rhinitis, Allergic

Smoking

Tobacco Industry

Tobacco Products*

Tobacco*

Biomarkers

Metals, Heavy

Figure

Reference

-

1. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Major findings from KNHANES (2018) and KYRBSS (2019). Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2019.2. Cho HJ, Kim HJ, Lee CM, Kim KW, Kim JY, Lee JA. Analysis on use pattern of heated tobacco products and their impact on quit smoking intention. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2018.3. Lee C, Kim S, Cheong YS. Issues of new types of tobacco (e-cigarette and heat-not-burn tobacco): from the perspective of ‘tobacco harm reduction’. J Korean Med Assoc. 2018; 61:181–190.

Article4. Mallock N, Pieper E, Hutzler C, Henkler-Stephani F, Luch A. Heated tobacco products: a review of current knowledge and initial assessments. Front Public Health. 2019; 7:287.

Article5. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press;2018.6. Simonavicius E, McNeill A, Shahab L, Brose LS. Heat-not-burn tobacco products: a systematic literature review. Tob Control. 2019; 28:582–594.

Article7. Auer R, Concha-Lozano N, Jacot-Sadowski I, Cornuz J, Berthet A. Heat-not-burn tobacco cigarettes: smoke by any other name. JAMA Intern Med. 2017; 177:1050–1052.8. St Helen G, Jacob III P, Nardone N, Benowitz NL. IQOS: examination of Philip Morris International's claim of reduced exposure. Tob Control. 2018; 27:Suppl 1. s30–s36.

Article9. Gotts JE, Jordt SE, McConnell R, Tarran R. What are the respiratory effects of e-cigarettes? BMJ. 2019; 366:l5275.

Article10. Putzhammer R, Doppler C, Jakschitz T, Heinz K, Forste J, Danzl K, Messner B, Bernhard D. Vapours of US and EU market leader electronic cigarette brands and liquids are cytotoxic for human vascular endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2016; 11:e0157337.

Article11. Moazed F, Chun L, Matthay MA, Calfee CS, Gotts J. Assessment of industry data on pulmonary and immunosuppressive effects of IQOS. Tob Control. 2018; 27:Suppl 1. s20–s25.

Article12. Leigh NJ, Tran PL, O'Connor RJ, Goniewicz ML. Cytotoxic effects of heated tobacco products (HTP) on human bronchial epithelial cells. Tob Control. 2018; 27:Suppl 1. s26–s29.

Article13. Nabavizadeh P, Liu J, Havel CM, Ibrahim S, Derakhshandeh R, Jacob III P, Springer ML. Vascular endothelial function is impaired by aerosol from a single IQOS HeatStick to the same extent as by cigarette smoke. Tob Control. 2018; 27:Suppl 1. s13–s19.

Article14. Goniewicz ML, Smith DM, Edwards KC, Blount BC, Caldwell KL, Feng J, Wang L, Christensen C, Ambrose B, Borek N, van Bemmel D, Konkel K, Erives G, Stanton CA, Lambert E, Kimmel HL, Hatsukami D, Hecht SS, Niaura RS, Travers M, Lawrence C, Hyland AJ. Comparison of nicotine and toxicant exposure in users of electronic cigarettes and combustible cigarettes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018; 1:e185937.

Article15. Skotsimara G, Antonopoulos AS, Oikonomou E, Siasos G, Ioakeimidis N, Tsalamandris S, Charalambous G, Galiatsatos N, Vlachopoulos C, Tousoulis D. Cardiovascular effects of electronic cigarettes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019; 26:1219–1228.

Article16. Glantz SA. PMI's own in vivo clinical data on biomarkers of potential harm in Americans show that IQOS is not detectably different from conventional cigarettes. Tob Control. 2018; 27:Suppl 1. s9–s12.

Article17. Chun L, Moazed F, Matthay M, Calfee C, Gotts J. Possible hepatotoxicity of IQOS. Tob Control. 2018; 27:Suppl 1. s39–s40.

Article18. Stephens WE. Comparing the cancer potencies of emissions from vapourised nicotine products including e-cigarettes with those of tobacco smoke. Tob Control. 2018; 27:10–17.

Article19. Wang MP, Ho SY, Leung LT, Lam TH. Electronic cigarette use and respiratory symptoms in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. JAMA Pediatr. 2016; 170:89–91.

Article20. McConnell R, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wang K, Urman R, Hong H, Unger J, Samet J, Leventhal A, Berhane K. Electronic cigarette use and respiratory symptoms in adolescents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017; 195:1043–1049.

Article21. Cho JH, Paik SY. Association between electronic cigarette use and asthma among high school students in South Korea. PLoS One. 2016; 11:e0151022.

Article22. Wills TA, Pagano I, Williams RJ, Tam EK. E-cigarette use and respiratory disorder in an adult sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019; 194:363–370.

Article23. Hedman L, Backman H, Stridsman C, Bosson JA, Lundbäck M, Lindberg A, Rönmark E, Ekerljung L. Association of electronic cigarette use with smoking habits, demographic factors, and respiratory symptoms. JAMA Netw Open. 2018; 1:e180789.

Article24. Bhatta DN, Glantz SA. Association of e-cigarette use with respiratory disease among adults: a longitudinal analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2020; 58:182–190.

Article25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2019. cited 2019 Dec 24. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html#latest-outbreak.26. Landman ST, Dhaliwal I, Mackenzie CA, Martinu T, Steele A, Bosma KJ. Life-threatening bronchiolitis related to electronic cigarette use in a Canadian youth. CMAJ. 2019; 191:E1321–E1331.

Article27. Alzahrani T, Pena I, Temesgen N, Glantz SA. Association between electronic cigarette use and myocardial infarction. Am J Prev Med. 2018; 55:455–461.

Article28. Osei AD, Mirbolouk M, Orimoloye OA, Dzaye O, Uddin SMI, Benjamin EJ, Hall ME, DeFilippis AP, Stokes A, Bhatnagar A, Nasir K, Blaha MJ. Association between e-cigarette use and cardiovascular disease among never and current combustible-cigarette smokers. Am J Med. 2019; 132:949–954.

Article29. Bhatta DN, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarette use and myocardial infarction among adults in the US Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019; 8:e012317.

Article30. Lee A, Lee SY, Lee KS. The use of heated tobacco products is associated with asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis in Korean adolescents. Sci Rep. 2019; 9:17699.

Article31. Levy DT, Borland R, Lindblom EN, Goniewicz ML, Meza R, Holford TR, Yuan Z, Luo Y, O'Connor RJ, Niaura R, Abrams DB. Potential deaths averted in USA by replacing cigarettes with e-cigarettes. Tob Control. 2018; 27:18–25.

Article32. Soneji SS, Sung HY, Primack BA, Pierce JP, Sargent JD. Quantifying population-level health benefits and harms of e-cigarette use in the United States. PLoS One. 2018; 13:e0193328.

Article33. Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016; 4:116–128.

Article34. Berry KM, Reynolds LM, Collins JM, Siegel MB, Fetterman JL, Hamburg NM, Bhatnagar A, Benjamin EJ, Stokes A. E-cigarette initiation and associated changes in smoking cessation and reduction: the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, 2013-2015. Tob Control. 2019; 28:42–49.

Article35. Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, Pesola F, Myers Smith K, Bisa lN, Li J, Parrott S, Sasieni P, Dawkins L, Ross L, Goniewicz M, Wu Q, McRobbie HJ. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:629–637.

Article36. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, Leventhal AM, Unger JB, Gibson LA, Yang J, Primack BA, Andrews JA, Miech RA, Spindle TR, Dick DM, Eissenberg T, Hornik RC, Dang R, Sargent JD. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017; 171:788–797.

Article37. Max WB, Sung HY, Lightwood J, Wang Y, Yao T. Modelling the impact of a new tobacco product: review of Philip Morris International's Population Health Impact Model as applied to the IQOS heated tobacco product. Tob Control. 2018; 27:Suppl 1. s82–s86.

Article38. Lee JA, Lee S, Cho HJ. The relation between frequency of e-cigarette use and frequency and intensity of cigarette smoking among South Korean adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017; 14:305.

Article39. Lim J, Lee JA, Fong GT, Yan M, Driezen P, Seo HG, Cho HJ. Awareness and use of e-cigarettes and vaping behaviors among Korean adult smokers: ITC 2016 Korean study. J Korean Soc Res Nicotine Tob. 2018; 9 Suppl 1:S11–S21.

Article40. Cho HJ, Kimm HJ, Lee CM, Kim KW, Kim JY, Lee JA. Analysis of heated tobacco product use and impact on smoking cessation for Korean adults. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Social Affair;2018.41. Popova L, Lempert LK, Glantz SA. Light and mild redux: heated tobacco products' reduced exposure claims are likely to be misunderstood as reduced risk claims. Tob Control. 2018; 27:Suppl 1. s87–s95.

Article42. El-Toukhy S, Baig SA, Jeong M, Byron MJ, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. Impact of modified risk tobacco product claims on beliefs of US adults and adolescents. Tob Control. 2018; 27:Suppl 1. s62–s69.

Article43. Glantz SA. Heated tobacco products: the example of IQOS. Tob Control. 2018; 27:Suppl 1. s1–s6.

Article44. McKelvey K, Popova L, Kim M, Chaffee BW, Vijayaraghavan M, Ling P, Halpern-Felsher B. Heated tobacco products likely appeal to adolescents and young adults. Tob Control. 2018; 27:Suppl 1. s41–s47.

Article45. Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, Chang JT, Anic GM, Wang TW, Creamer MR, Jamal A, Ambrose BK, King BA. e-cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA. 2019; 322:2095–2103.

Article46. Hoffmann D, Hoffmann I, El-Bayoumy K. The less harmful cigarette: a controversial issue. a tribute to Ernst L. Wynder. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001; 14:767–790.

Article47. Law MR, Wald NJ. Environmental tobacco smoke and ischemic heart disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003; 46:31–38.

Article48. Flanders WD, Lally CA, Zhu BP, Henley SJ, Thun MJ. Lung cancer mortality in relation to age, duration of smoking, and daily cigarette consumption: results from Cancer Prevention Study II. Cancer Res. 2003; 63:6556–6562.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- International regulatory overview of electronic cigarettes and heated tobacco products

- Directions and Challenges in Smoking Cessation Treatment

- The Government Policies of New Tobacco Products: Strategies for Managing Electronic Cigarettes and Heated Tobacco Products

- Evolution of tobacco products

- The Impact of Heated Tobacco Products on Smoking Cessation, Tobacco Use, and Tobacco Sales in South Korea