Ann Rehabil Med.

2019 Dec;43(6):686-699. 10.5535/arm.2019.43.6.686.

Rehabilitation Intervention for Individuals With Heart Failure and Fatigue to Reduce Fatigue Impact: A Feasibility Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Occupational Therapy, College of Allied Health Sciences, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA. kimyo15@ecu.edu

- 2Department of Occupational Therapy, AdventHealth University, Orlando, FL, USA.

- 3College of Nursing, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA.

- 4Department of Nursing Science, College of Nursing, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA.

- KMID: 2468695

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2019.43.6.686

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate feasibility of recruitment, tablet use in intervention delivery, and use of self-report outcome measures and to analyze the effect of Energy Conservation plus Problem-Solving Therapy versus Health Education interventions for individuals with heart failure-associated fatigue.

METHODS

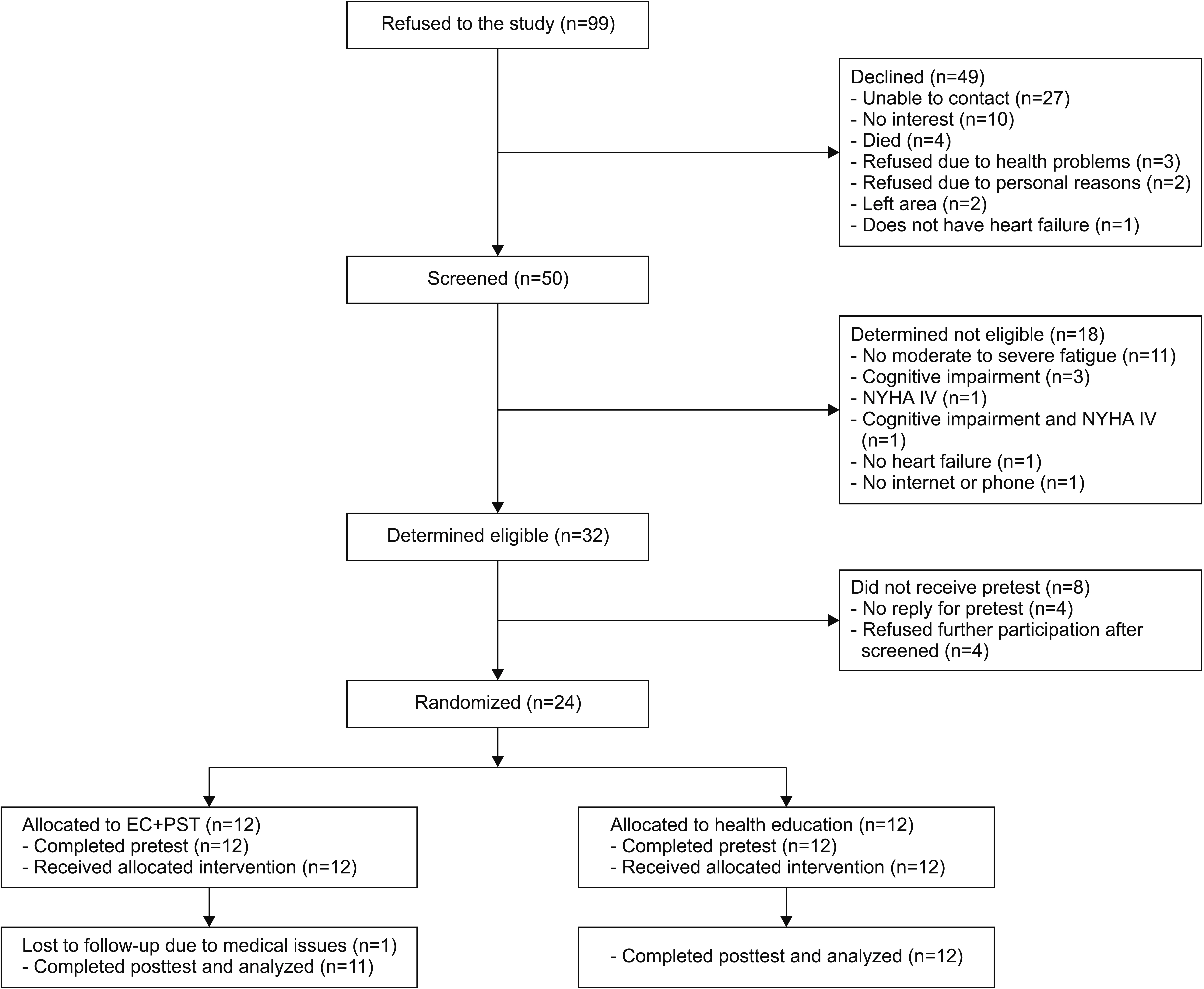

This feasibility study was a block-randomized controlled trial involving 23 adults, blinded to their group assignment, in a rural southern area in the United States. Individuals with heart failure and fatigue received the interventions for 6 weeks through videoconferencing or telephone. Participants were taught to solve their fatigue-related problems using energy conservation strategies and the process of Problem-Solving Therapy or educated about health-related topics.

RESULTS

The recruitment rate was 23%. All participants completed the study participation according to their group assignment, except for one participant in the Energy Conservation plus Problem-Solving Therapy group. Participants primarily used the tablet (n=21) rather than the phone (n=2). Self-report errors were noted on Activity Card Sort (n=23). Reported fatigue was significantly lower for both the Energy Conservation plus Problem-Solving Therapy (p=0.03, r=0.49) and Health Education (p=0.004, r=0.64) groups. The Health Education group reported significantly lower fatigue impact (p=0.019, r=0.48). Participation was significantly different in low-physical demand leisure activities (p=0.008; r=0.55) favoring the Energy Conservation plus Problem-Solving Therapy group.

CONCLUSION

The recruitment and delivery of the interventions were feasible. Activity Card Sort may not be appropriate for this study population due to recall bias. The interventions warrant future research to reduce fatigue and decrease participation in sedentary activities (Clinical Trial Registration number: NCT03820674).

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Roger VL. Epidemiology of heart failure. Circ Res. 2013; 113:646–59.

Article2. Butrous H, Hummel SL. Heart failure in older adults. Can J Cardiol. 2016; 32:1140–7.

Article3. Tang WH, Francis GS. Clinical evaluation of heart failure. In : Mann DL, Felker GM, editors. Heart failure: a companion to Braunwald’s heart disease. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier;2016. p. 421–37.4. Smith OR, van den Broek KC, Renkens M, Denollet J. Comparison of fatigue levels in patients with stroke and patients with end-stage heart failure: application of the fatigue assessment scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008; 56:1915–9.

Article5. Evangelista LS, Moser DK, Westlake C, Pike N, TerGalstanyan A, Dracup K. Correlates of fatigue in patients with heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008; 23:12–7.

Article6. Falk K, Granger BB, Swedberg K, Ekman I. Breaking the vicious circle of fatigue in patients with chronic heart failure. Qual Health Res. 2007; 17:1020–7.

Article7. Hägglund L, Boman K, Lundman B. The experience of fatigue among elderly women with chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008; 7:290–5.

Article8. Dunlay SM, Roger VL. Understanding the epidemic of heart failure: past, present, and future. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2014; 11:404–15.

Article9. Kluger BM, Krupp LB, Enoka RM. Fatigue and fatigability in neurologic illnesses: proposal for a unified taxonomy. Neurology. 2013; 80:409–16.

Article10. DeLuca J. Fatigue its definition, its study, and its future. In : DeLuca J, editor. Fatigue as a window to the brain. Cambridge: MIT Press;2005. p. 319–326.11. Lou JS. Physical and mental fatigue in Parkinson’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment. Drugs Aging. 2009; 26:195–208.12. Pozehl B, Duncan K, Hertzog M. The effects of exercise training on fatigue and dyspnea in heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008; 7:127–32.

Article13. Corvera-Tindel T, Doering LV, Woo MA, Khan S, Dracup K. Effects of a home walking exercise program on functional status and symptoms in heart failure. Am Heart J. 2004; 147:339–46.

Article14. Oka RK, De Marco T, Haskell WL, Botvinick E, Dae MW, Bolen K, et al. Impact of a home-based walking and resistance training program on quality of life in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2000; 85:365–9.

Article15. Tsai BM. Feasibility and effectiveness of e-therapy on fatigue management in home-based older adults with congestive heart failure [dissertation]. Buffalo: University at Buffalo;2008.16. Mathiowetz VG, Finlayson ML, Matuska KM, Chen HY, Luo P. Randomized controlled trial of an energy conservation course for persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005; 11:592–601.17. Kim YJ, Rogers JC, Raina KD, Callaway CW, Rittenberger JC, Leibold ML, et al. An intervention for cardiac arrest survivors with chronic fatigue: a feasibility study with preliminary outcomes. Resuscitation. 2016; 105:109–15.

Article18. Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale: application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989; 46:1121–3.19. Woodford HJ, George J. Cognitive assessment in the elderly: a review of clinical methods. QJM. 2007; 100:469–84.

Article20. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987; 40:373–83.

Article21. Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging. 1997; 12:277–87.

Article22. Holm B, Jacobsen S, Skjodt H, Klarlund M, Jensen T, Hetland ML, et al. Keitel Functional Test for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: translation, reliability, validity, and responsiveness. Phys Ther. 2008; 88:664–78.

Article23. Rosen LD, Whaling K, Carrier LM, Cheever NA, Rokkum J. The media and technology usage and attitudes scale: an empirical investigation. Comput Human Behav. 2013; 29:2501–11.

Article24. Lai JS, Cella D, Choi S, Junghaenel DU, Christodoulou C, Gershon R, et al. How item banks and their application can influence measurement practice in rehabilitation medicine: a PROMIS fatigue item bank example. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011; 92(10 Suppl):S20–7.

Article25. Cella D, Lai JS, Jensen SE, Christodoulou C, Junghaenel DU, Reeve BB, et al. PROMIS fatigue item bank had clinical validity across diverse chronic conditions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016; 73:128–34.

Article26. Frith J, Newton J. Fatigue impact scale. Occup Med (Lond). 2010; 60:159.

Article27. Baum CM, Edwards D. ACS: activity card sort. 2nd ed. Bethesda: AOTA Press;2008.28. Cisco. Cisco WebEx Meetings [Internet]. [place unknown]: Cisco WebEx;c2019. [cited 2019 Nov 15]. Available from: http://www.webex.com.29. Amazon. Fire Tablet with Alexa, 7” Display, 8 GB, Black - with special offers (previous generation - 5th) [Internet]. [place unknown]: Amazon.com;c2019. [cited 2019 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.amazon.com/Amazon-Fire-7-Tablet-5th-Generation/dp/B00TSUGXKE#customerReviews.30. Matthews MM. Cardiac and pulmonary disease. In : Pendleton HM, Schultz-Krohn W, editors. Pedretti’s occupational therapy-e-book: practice skills for physical dysfunction. St. Louis: Elsevier Inc;2018. p. 1117–33.31. Nezu AM, Nezu CM, D’Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving therapy: a treatment manual. New York: Springer;2013.32. Tickle-Degnen L. From the general to the specific: using meta-analytic reports in clinical decision making. Eval Health Prof. 2001; 24:308–26.33. Powell LH, Calvin JE Jr, Richardson D, Janssen I, Mendes de Leon CF, Flynn KJ, et al. Self-management counseling in patients with heart failure: the heart failure adherence and retention randomized behavioral trial. JAMA. 2010; 304:1331–8.34. Dracup K, Moser DK, Pelter MM, Nesbitt TS, Southard J, Paul SM, et al. Randomized, controlled trial to improve self-care in patients with heart failure living in rural areas. Circulation. 2014; 130:256–64.

Article35. Hageman PA, Pullen CH, Hertzog M, Pozehl B, Eisenhauer C, Boeckner LS. Web-based interventions alone or supplemented with peer-led support or professional email counseling for weight loss and weight maintenance in women from rural communities: results of a clinical trial. J Obes. 2017; 2017:1602627.

Article36. Bale B. Optimizing hypertension management in underserved rural populations. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010; 102:10–7.

Article37. Wendebourg MJ, Heesen C, Finlayson M, Meyer B, Pottgen J, Kopke S. Patient education for people with multiple sclerosis-associated fatigue: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0173025.

Article38. Bennett S, Pigott A, Beller EM, Haines T, Meredith P, Delaney C. Educational interventions for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016; 11:CD008144.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Fatigue of Pilots and the Risk Management

- Fatigue and Exercise in Middle-aged Women

- Cardiac Rehabilitation of Heart Failure

- A Study on the Pilot Fatigue Measurement Methods for Fatigue Risk Management

- Fatigue and Fatigue-Regulation Behaviors of Undergraduates in Courses Related to Public Health and Undergraduates in Courses not Related to Public Health