Yonsei Med J.

2020 Feb;61(2):154-160. 10.3349/ymj.2020.61.2.154.

Prediction Model for Massive Transfusion in Placenta Previa during Cesarean Section

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea. choisj@yonsei.ac.kr

- 2Center of Biomedical Data Science, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea.

- 3Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea.

- 4Department of Laboratory Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea.

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 6Department of Precision Medicine and Biostatistics, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea.

- KMID: 2468490

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2020.61.2.154

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Recently, obstetric massive transfusion protocols have shifted toward early intervention. This study aimed to develop a prediction model for transfusion of ≥5 units of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) during cesarean section in women with placenta previa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a cohort study including 287 women with placenta previa who delivered between September 2011 and April 2018. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to test the association between clinical factors, ultrasound factors, and massive transfusion. For the external validation set, we obtained data (n=50) from another hospital.

RESULTS

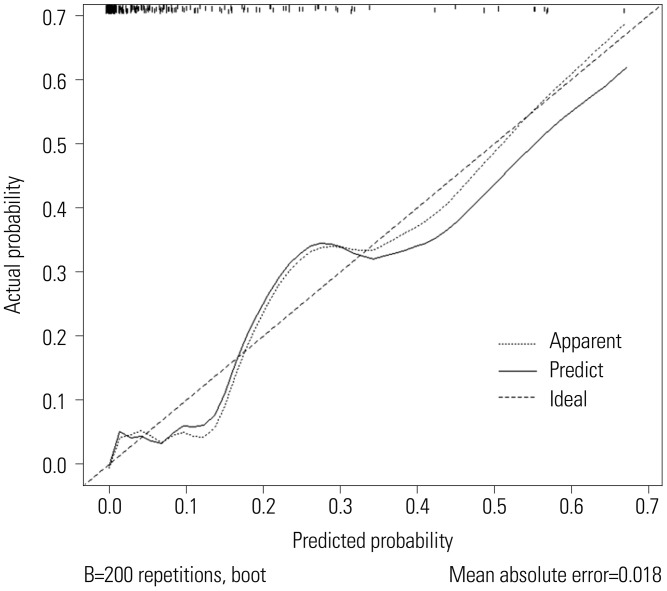

We formulated a scoring model for predicting transfusion of ≥5 units of PRBCs, including maternal age, degree of previa, grade of lacunae, presence of a hypoechoic layer, and anterior placentation. For example, total score of 223/260 had a probability of 0.7 for massive transfusion. Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test indicated that the model was suitable (p>0.05). The area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) was 0.922 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.89-0.95]. In external validation, the discrimination was good, with an AUC value of 0.833 (95% CI 0.70-0.92) for this model. Nomogram calibration plots indicated good agreement between the predicted and observed outcomes, exhibiting close approximation between the predicted and observed probability.

CONCLUSION

We constructed a scoring model for predicting massive transfusion during cesarean section in women with placenta previa. This model may help in determining the need to prepare an appropriate amount of blood products and the optimal timing of blood transfusion.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Silver RM. Abnormal placentation: placenta previa, vasa previa, and placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 126:654–668. PMID: 26244528.2. Rouse DJ, MacPherson C, Landon M, Varner MW, Leveno KJ, Moawad AH, et al. Blood transfusion and cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 108:891–897. PMID: 17012451.

Article3. Silver RM, Branch DW. Placenta accreta spectrum. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:1529–1536. PMID: 29669225.

Article4. Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Maggio L, Hauspurg AK, Sperling JD, Chauhan SP, et al. Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage: a comparison of 4 national guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 213:76.e1–76.e10. PMID: 25731692.

Article5. Weiniger CF, Elram T, Ginosar Y, Mankuta D, Weissman C, Ezra Y. Anaesthetic management of placenta accreta: use of a pre-operative high and low suspicion classification. Anaesthesia. 2005; 60:1079–1084. PMID: 16229692.

Article6. Mansfield PF, Hohn DC, Fornage BD, Gregurich MA, Ota DM. Complications and failures of subclavian-vein catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1994; 331:1735–1738. PMID: 7984193.

Article7. Snyder CW, Weinberg JA, McGwin G Jr, Melton SM, George RL, Reiff DA, et al. The relationship of blood product ratio to mortality: survival benefit or survival bias? J Trauma. 2009; 66:358–362. PMID: 19204508.

Article8. Pacheco LD, Saade GR, Costantine MM, Clark SL, Hankins GD. An update on the use of massive transfusion protocols in obstetrics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016; 214:340–344. PMID: 26348379.

Article9. Finberg HJ, Williams JW. Placenta accreta: prospective sonographic diagnosis in patients with placenta previa and prior cesarean section. J Ultrasound Med. 1992; 11:333–343. PMID: 1522623.

Article10. Gibbins KJ, Einerson BD, Varner MW, Silver RM. Placenta previa and maternal hemorrhagic morbidity. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018; 31:494–499. PMID: 28140723.

Article11. Farquhar CM, Li Z, Lensen S, McLintock C, Pollock W, Peek MJ, et al. Incidence, risk factors and perinatal outcomes for placenta accreta in Australia and New Zealand: a case-control study. BMJ Open. 2017; 7:e017713.

Article12. Baldwin HJ, Patterson JA, Nippita TA, Torvaldsen S, Ibiebele I, Simpson JM, et al. Antecedents of abnormally invasive placenta in primiparous women: risk associated with gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 131:227–233. PMID: 29324602.13. Fitzpatrick KE, Sellers S, Spark P, Kurinczuk JJ, Brocklehurst P, Knight M. Incidence and risk factors for placenta accreta/increta/percreta in the UK: a national case-control study. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e52893. PMID: 23300807.

Article14. Getahun D, Oyelese Y, Salihu HM, Ananth CV. Previous cesarean delivery and risks of placenta previa and placental abruption. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 107:771–778. PMID: 16582111.

Article15. Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Erfani H, Clark SL, Shamshirsaz AA, Nassr AA, et al. Outcomes of planned compared with urgent deliveries using a multidisciplinary team approach for morbidly adherent placenta. Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 131:234–241. PMID: 29324609.

Article16. Publications Committee, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Belfort MA. Placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 203:430–439. PMID: 21055510.

Article17. Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee opinion no. 529: placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 120:207–211. PMID: 22914422.18. Marsoosi V, Ghotbizadeh F, Hashemi N, Molaei B. Development of a scoring system for prediction of placenta accreta and determine the accuracy of its results. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018; 11. 04. [Epub]. Available at: . DOI: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1531119.

Article19. Rac MW, Dashe JS, Wells CE, Moschos E, McIntire DD, Twickler DM. Ultrasound predictors of placental invasion: the Placenta Accreta Index. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 212:343.e1–343.e7. PMID: 25446658.

Article20. Tovbin J, Melcer Y, Shor S, Pekar-Zlotin M, Mendlovic S, Svirsky R, et al. Prediction of morbidly adherent placenta using a scoring system. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016; 48:504–510. PMID: 26574157.

Article21. Guy GP, Peisner DB, Timor-Tritsch IE. Ultrasonographic evaluation of uteroplacental blood flow patterns of abnormally located and adherent placentas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990; 163:723–727. PMID: 2206064.

Article22. Yang JI, Lim YK, Kim HS, Chang KH, Lee JP, Ryu HS. Sonographic findings of placental lacunae and the prediction of adherent placenta in women with placenta previa totalis and prior Cesarean section. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 28:178–182. PMID: 16858740.

Article23. D'Antonio F, Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Timor-Trisch I, Cali G. Placenta accreta spectrum disorders: prenatal diagnosis still lacks clinical correlation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018; 97:773–775. PMID: 29924394.24. Pivano A, Alessandrini M, Desbriere R, Agostini A, Opinel P, d'Ercole C, et al. A score to predict the risk of emergency caesarean delivery in women with antepartum bleeding and placenta praevia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015; 195:173–176. PMID: 26550944.

Article25. Tanimura K, Morizane M, Deguchi M, Ebina Y, Tanaka U, Ueno Y, et al. A novel scoring system for predicting adherent placenta in women with placenta previa. Placenta. 2018; 64:27–33. PMID: 29626978.

Article26. Choi SJ, Song SE, Jung KL, Oh SY, Kim JH, Roh CR. Antepartum risk factors associated with peripartum cesarean hysterectomy in women with placenta previa. Am J Perinatol. 2008; 25:37–41. PMID: 18095214.

Article27. Hasegawa J, Matsuoka R, Ichizuka K, Mimura T, Sekizawa A, Farina A, et al. Predisposing factors for massive hemorrhage during Cesarean section in patients with placenta previa. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 34:80–84. PMID: 19565529.

Article28. Lee JY, Ahn EH, Kang S, Moon MJ, Jung SH, Chang SW, et al. Scoring model to predict massive post-partum bleeding in pregnancies with placenta previa: a retrospective cohort study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018; 44:54–60. PMID: 29067758.

Article29. Bose P, Regan F, Paterson-Brown S. Improving the accuracy of estimated blood loss at obstetric haemorrhage using clinical reconstructions. BJOG. 2006; 113:919–924. PMID: 16907938.

Article30. Yoon SY, You JY, Choi SJ, Oh SY, Kim JH, Roh CR. A combined ultrasound and clinical scoring model for the prediction of peripartum complications in pregnancies complicated by placenta previa. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014; 180:111–115. PMID: 25079491.

Article31. Kim JW, Lee YK, Chin JH, Kim SO, Lee MY, Won HS, et al. Development of a scoring system to predict massive postpartum transfusion in placenta previa totalis. J Anesth. 2017; 31:593–600. PMID: 28466102.

Article32. Ball CG. Damage control resuscitation: history, theory and technique. Can J Surg. 2014; 57:55–60. PMID: 24461267.

Article33. Holcomb JB, Jenkins D, Rhee P, Johannigman J, Mahoney P, Mehta S, et al. Damage control resuscitation: directly addressing the early coagulopathy of trauma. J Trauma. 2007; 62:307–310. PMID: 17297317.

Article34. Holcomb JB, Wade CE, Michalek JE, Chisholm GB, Zarzabal LA, Schreiber MA, et al. Increased plasma and platelet to red blood cell ratios improves outcome in 466 massively transfused civilian trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2008; 248:447–458. PMID: 18791365.

Article35. Hess JR, Holcomb JB, Hoyt DB. Damage control resuscitation: the need for specific blood products to treat the coagulopathy of trauma. Transfusion. 2006; 46:685–686. PMID: 16686833.

Article36. Waters JH. Role of the massive transfusion protocol in the management of haemorrhagic shock. Br J Anaesth. 2014; 113 Suppl 2:ii3–ii8. PMID: 25498580.

Article37. Cunningham FG, Nelson DB. Disseminated intravascular coagulation syndromes in obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 126:999–1011. PMID: 26444122.

Article38. Bleeker SE, Moll HA, Steyerberg EW, Donders AR, Derksen-Lubsen G, Grobbee DE, et al. External validation is necessary in prediction research: a clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003; 56:826–832. PMID: 14505766.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Predictive Model of Massive Hemorrhage in Pregnant Women of Previous Cesarean Section with Placenta Previa

- Management of massive hemorrhage in pregnant women with placenta previa

- Probability Model of Massive Hemorrhage in Patients with Placenta Previa

- Probability Model of Blood Transfusion for Cesarean Delivery Complicated by Placenta Previa

- The comparison of the pregnancy outcomes according to the types of placenta previa