Korean J Ophthalmol.

2019 Dec;33(6):514-519. 10.3341/kjo.2019.0092.

Primary Ocular Toxoplasmosis Presenting to Uveitis Services in a Non-endemic Setting

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Auckland District Health Board, Auckland, New Zealand. RiyazB@adhb.govt.nz

- 2Department of Ophthalmology, Waikato District Health Board, Auckland, New Zealand.

- KMID: 2465131

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/kjo.2019.0092

Abstract

- PURPOSE

This study sought to describe the different clinical features and presentations of primary ocular toxoplasmosis in a setting not demonstrating an outbreak of disease.

METHODS

This was a retrospective review of patients presenting to uveitis management services in Auckland and Hamilton, New Zealand between 2003 to 2018 with uveitis and positive toxoplasmosis immunoglobulin M serology.

RESULTS

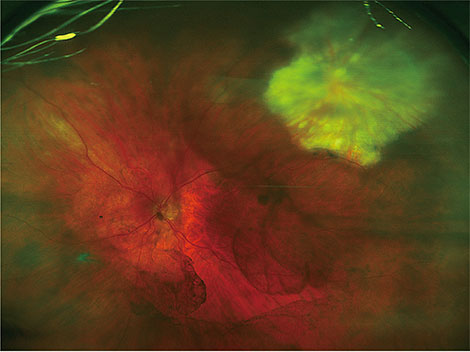

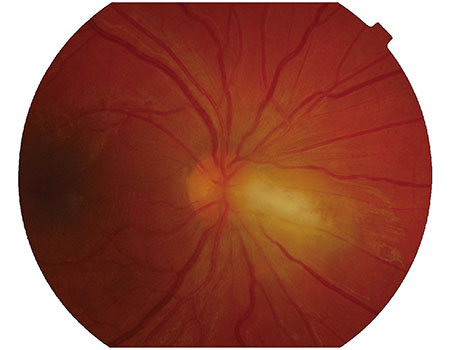

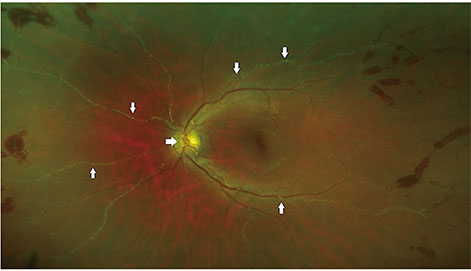

We identified 16 patients with primary acquired toxoplasmosis infection and ocular involvement. The mean age was 53 years. Systemic symptoms were reported in 56% (9 / 16). Visual acuity was reduced to 20 / 30 or less in 50% of patients (8 / 16). A single focus of retinitis without a pigmented scar was the salient clinical feature in 69% (11 / 16). Optic nerve inflammation was the sole clinical finding in 19% (3 / 16). Bilateral arterial vasculitis was the sole clinical finding in 13% (2 / 16). A delay in the diagnosis of toxoplasmosis of more than two weeks occurred in 38% (6 / 16) due to an initial alternative diagnosis. Antibiotic therapy was prescribed in all cases. Vision was maintained or improved in 69% (11 / 16) at the most recent follow-up visit (15 months to 10 years). Relapse occurred in 69% (11 / 16), typically within four years from the initial presentation.

CONCLUSIONS

Primary ocular toxoplasmosis presenting in adulthood is a relatively uncommon cause of posterior uveitis in New Zealand. This condition should be considered in any patient presenting with retinitis or optic nerve inflammation without a retinochoroidal scar. This disease tends to relapse; thus, close follow-up is required.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Gilbert RE, Stanford MR. Is ocular toxoplasmosis caused by prenatal or postnatal infection? Br J Ophthalmol. 2000; 84:224–226.2. Calderaro A, Piccolo G, Peruzzi S, et al. Evaluation of Toxoplasma gondii immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM assays incorporating the newVidia analyzer system. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008; 15:1076–1079.3. Murat JB, Dard C, Fricker Hidalgo H, et al. Comparison of the Vidas system and two recent fully automated assays for diagnosis and follow-up of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women and newborns. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013; 20:1203–1212.4. Balasundaram MB, Andavar R, Palaniswamy M, Venkatapathy N. Outbreak of acquired ocular toxoplasmosis involving 248 patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010; 128:28–32.5. Burnett AJ, Shortt SG, Isaac-Renton J, et al. Multiple cases of acquired toxoplasmosis retinitis presenting in an outbreak. Ophthalmology. 1998; 105:1032–1037.6. Butler NJ, Furtado JM, Winthrop KL, Smith JR. Ocular toxoplasmosis II: clinical features, pathology and management. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013; 41:95–108.7. Balansard B, Bodaghi B, Cassoux N, et al. Necrotising retinopathies simulating acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005; 89:96–101.8. Morris A, Croxson M. Serological evidence of Toxoplasma gondii infection among pregnant women in Auckland. N Z Med J. 2004; 117:U770.9. Zarkovic A, McMurray C, Deva N, et al. Seropositivity rates for Bartonella henselae, Toxocara canis and Toxoplasma gondii in New Zealand blood donors. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007; 35:131–134.10. de Smet MD. Papillophlebitis and uveitis as a manifestation of post-streptococcal uveitis syndrome. Eye (Lond). 2009; 23:985–987.11. Lai CC, Chang YS, Li ML, et al. Acute anterior uveitis and optic neuritis as ocular complications of influenza A infection in an 11-year-old boy. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2011; 48 Online:e30–e33.12. Fekkar A, Bodaghi B, Touafek F, et al. Comparison of immunoblotting, calculation of the Goldmann-Witmer coefficient, and real-time PCR using aqueous humor samples for diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008; 46:1965–1967.13. Fardeau C, Romand S, Rao NA, et al. Diagnosis of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis with atypical clinical features. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002; 134:196–203.14. Montoya JG, Parmley S, Liesenfeld O, et al. Use of the polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106:1554–1563.15. Labalette P, Delhaes L, Margaron F, et al. Ocular toxoplasmosis after the fifth decade. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002; 133:506–515.16. Errera MH, Goldschmidt P, Batellier L, et al. Real-time polymerase chain reaction and intraocular antibody production for the diagnosis of viral versus toxoplasmic infectious posterior uveitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011; 249:1837–1846.17. Harper TW, Miller D, Schiffman JC, Davis JL. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of aqueous and vitreous specimens in the diagnosis of posterior segment infectious uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009; 147:140–147.