J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc.

2019 Nov;58(4):322-330. 10.4306/jknpa.2019.58.4.322.

Depression and Gap between Perceived- and Self-Willingness-to-Pay for Labor in Community-Dwelling Full-Time Female Homemakers

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Psychiatry, Jeonbuk Provincial Maeumsarang Hospital, Wanju, Korea. tyhwang73@naver.com

- 2Insan Research Institute for Psychiatry, Jeonbuk Provincial Maeumsarang Hospital, Wanju, Korea.

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Medical Foundation Yong-In Mental Hospital, Yongin, Korea.

- 4Yong-In Mental Health Welfare Center · Yong-In Suicide Prevention Center, Yongin, Korea.

- KMID: 2465052

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4306/jknpa.2019.58.4.322

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Knowledge of labor and mental health status of full-time homemakers is essential for the health and maintenance of our society. This study investigated the current states of mental health and related factors in full-time female homemakers, and the effect of the gap between socially evaluated (perceived)- and self-evaluated value of labor of full-time female homemakers on depression.

METHODS

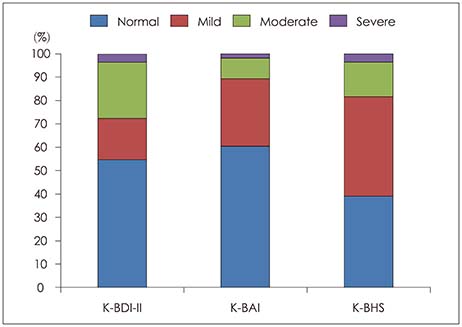

Participants were sequentially recruited from among community-dwelling full-time female homemakers, and assessed using structured questionnaires composed of general items as well as Korean versions of Beck Depression Inventory-II (K-BDI-II), Beck Anxiety Inventory (K-BAI), and Beck Hopelessness Scale (K-BHS). The willingness-to-pay (WTP) approach was used to measure perceived and self-evaluated values of labor of full-time homemakers.

RESULTS

A total of 169 participants were enrolled. The analytical results showed that 45.2% of participants were positive when screened by BDI (mild to severe depression), 39.6% positive by K-BAI (anxiety), and 60.9% positive by K-BHS (hopelessness). Multiple regression analysis of significant factors related to depression were burden of nurturing (t=3.99, p<0.001), monthly income (t=−3.24, p<0.01), and relationship with husband (t=−3.03, p<0.01). Logistic regression analysis showed that the gap between perceived- and self-WTP was a significant negative impact factor for depression level transition (K-BDI-II≥14) (p=0.025, odds ratio=0.995).

CONCLUSION

The results showed that full-time female homemakers are under relatively risky conditions and are associated with blind spots in the mental health perspective, suggesting that social support and a political approach are necessary for the maintenance of mental health of full-time female homemakers.

Figure

Reference

-

1. American Psychiatry Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition: DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychaitry Association;2013.2. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock's comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer;2017. p. 1614–1618.3. World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Switzerland: World Health Organization;2008.4. Suh GH, Kim JK, Yeon BK, Park SK, Yoo KY, Yang BK, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of dementia and depression in the elderly. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2000; 39:809–824.5. Cho MJ, Nam JJ, Suh GH. Prevalence of symptoms of depression in a nationwide sample of Korean adults. Psychiatry Res. 1998; 81:341–352.

Article6. Park JH, Lee JJ, Lee SB, Huh Y, Choi EA, Youn JC, et al. Prevalence of major depressive disorder and minor depressive disorder in an elderly Korean population: results from the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging (KLoSHA). J Affect Disord. 2010; 125:234–240.

Article7. Djernes JK. Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006; 113:372–387.

Article8. Wang J, Smailes E, Sareen J, Schmitz N, Fick G, Patten S. Three jobrelated stress models and depression: a population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012; 47:185–193.

Article9. Smith PM, Bielecky A. The impact of changes in job strain and its components on the risk of depression. Am J Public Health. 2012; 102:352–358.

Article10. Siegrist J, Starke D, Chandola T, Godin I, Marmot M, Niedhammer I, et al. The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Soc Sci Med. 2004; 58:1483–1499.

Article11. Chandola T, Martikainen P, Bartley M, Lahelma E, Marmot M, Michikazu S, et al. Does conflict between home and work explain the effect of multiple roles on mental health? A comparative study of Finland, Japan, and the UK. Int J Epidemiol. 2004; 33:884–893.

Article12. Gramm WS. Labor, work, and leisure: human well-being and the optimal allocation of time. J Econ Issues. 1987; 21:167–188.

Article13. Korea Statistical Information Service. Household production satellite account 1999–2014. cited 2019 May 26. Available from: http://kosis.kr.14. Hwang NH. Why should full-time homemaker's housework be ‘unpaid’? Hankyung Magazine [online]. 2018. 08. 01. cited 2019 May 26. Available from: http://magazine.hankyung.com/business/apps/news?popup=0&nid=01&c1=1&nkey=2018073001183000161&mode=sub_view.15. Moon SJ, Kim HY. The benefit and cost of full - time housewife occupation. Fam Environ Res. 1994; 32:15–29.16. Won YS. A study on the problems of Matrimonial Property System and their solution in Korean Family Law. J Asian Women. 1992; 31:91–121.17. Chang IS, Woo HB. Difference in housework hours between married women and men and their influence factors. Women Stud. 2017; 95:41–72.

Article18. Mariani AW, Pêgo-Fernandes PM. Willingness to pay… What??? Sao Paulo Med J. 2014; 132:131–132.

Article19. Bala MV, Mauskopf JA, Wood LL. Willingness to pay as a measure of health benefits. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999; 15:9–18.

Article20. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation;1996.21. Lim SY, Lee EJ, Jeong SW, Kim HC, Jeong CH, Jeon TY, et al. The validation study of Beck Depression Scale 2 in Korean version. Anxiety Mood. 2011; 7:48–53.22. Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck anxiety inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation;1990.23. Yook SP, Kim ZS. A clinical study on the Korean version of Beck Anxiety Inventory: comparative study of patient and non-patient. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1997; 16:185–197.24. Beck AT, Steer RA. BHS, Beck hopelessness scale: manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation;1988.25. Kim S, Lee EH, Hwang ST, Hong SH, Lee K, Kim JH. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Beck Hopelessness Scale. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2015; 54:84–90.

Article26. Goldsmith RE. Dimensionality of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Soc Behav Pers. 1986; 1:253–264.27. Lee J, Nam S, Lee MK, Lee JH, Lee SM. Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale: analysis of item-level validity. Korean J Couns Psychother. 2009; 21:173–189.28. Ministry of Health and Welfare. The Survey of Mental Disorders in Korea. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2017. p. 97–110.29. Ha EH, Oh KJ, Kim EJ. Depressive symptoms and family relationship of married women : focused on parenting stress and marital dissatisfaction. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1999; 18:79–93.30. Shin SC, Kim MK, Yun KS, Kim JH, Lee MS, Moon SJ, et al. The center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D): its use in Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 1991; 30:752–767.31. Busch FN, Rudden M, Shapiro T. Psychodynamic treatment of depression. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.;2004. p. 13–30.32. Moon SJ. A study on the perception of household work's value. J Korean Home Manage Assoc. 1991; 9:285–302.33. Park JH, Yoo YJ. Individual and family relational factors associated with housewives' depression. J Fam Relat. 1999; 4:91–119.34. Park JH, Yoo YJ. The effect of family strengths and wives' self-esteem on depression among married women. J Korean Home Manage Assoc. 2000; 18:155–174.35. Brockner J, John G. Improving the performance of low self-esteem individuals: an attributional approach. Acad Manag J. 1983; 26:642–656.

Article36. Roe Ey, Kwon JH. The role of self-esteem and marital relationship on women's depression II. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1997; 16:41–54.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Influence of the Burden of Nurturing and Depression on Sleep Quality in Female Full-Time Homemakers : The Moderated Mediating Effect of Monthly Income

- Women's Willingness to Pay for Cancer Screenin

- Perceived Social Support, Instrumental Support Needs, and Depression of Elderly Women

- Factors Influencing Depression with Emotional Labor among Workers in the Service Industry

- Perceived Benefits and Barriers of Exercise in Community-Dwelling Adults at a Local City in Korea