J Bone Metab.

2019 Nov;26(4):253-261. 10.11005/jbm.2019.26.4.253.

Estimating the Fiscal Costs of Osteoporosis in Korea Applying a Public Economic Perspective

- Affiliations

-

- 1Unit of Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Pharmacy, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. m.connolly@rug.nl

- 2Global Market Access Solutions SÃ rl, St-Prex, Switzerland.

- 3Division of Endocrinology, Department of Internal Medicine, Wonkwang University Sanbon Hospital, Wonkwang University School of Medicine, Gunpo, Korea.

- KMID: 2465027

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.11005/jbm.2019.26.4.253

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Osteoporosis and attributable fractures are disruptive health events that can cause short and long-term cost consequences for families, health service and government. In this fracture-based scenario analysis we evaluate the broader public economic consequences for the Korean government based on fractures that can occur at 3 different ages.

METHODS

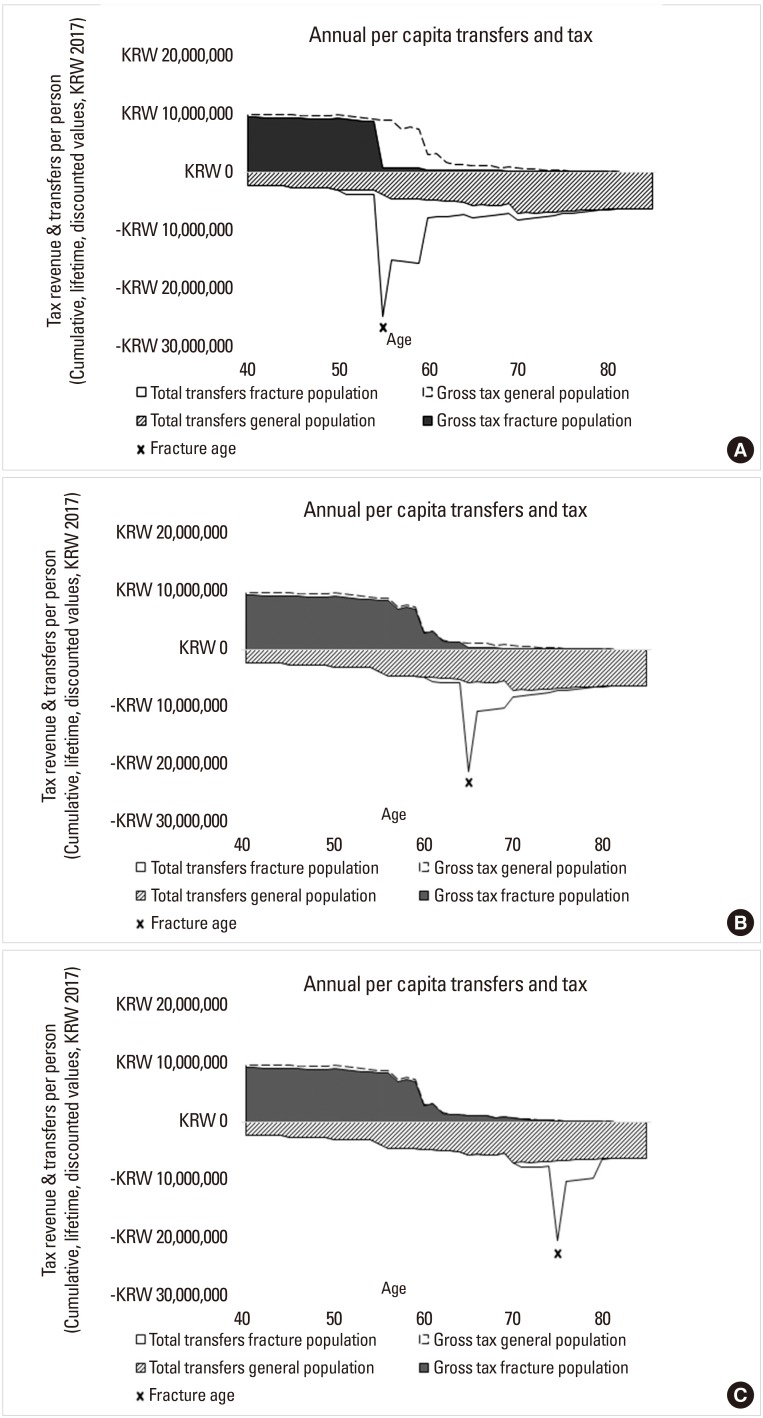

We developed a public economic modelling framework based on population averages in Korea for earnings, direct taxes, indirect taxes, disability payments, retirement, pension payments, and osteoporosis health costs. Applying a scenario analysis, we estimated the cumulative average per person fiscal consequences of osteoporotic fractures occurring at different ages 55, 65, and 75 compared to average non-fracture individuals of comparable ages to estimate resulting costs for government in relation to lost tax revenue, disability payments, pension costs, and healthcare costs. All costs are calculated between the ages of 50 to 80 in Korean Won (KRW) and discounted at 0.5%.

RESULTS

From the scenarios explored, fractures occurring at age 55 are most costly for government with increased disability and pension payments of KRW 26,048,400 and KRW 41,094,206 per person, respectively, compared to the non-fracture population. A fracture can result in reduction in lifetime direct and indirect taxes resulting in KRW 53,648,886 lost tax revenue per person for government compared to general population.

CONCLUSIONS

The fiscal consequences of osteoporotic fractures for government vary depending on the age at which they occur. Fiscal benefits for government are greater when fractures are prevented early due to the potential to prevent early retirement and keeping people in the labor force to the degree that is observed in non-fracture population.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. The International Osteoporosis Foundation. Broken bones, broken lives: A roadmap to solve the fragility fracture crisis in Europe. Nyon, CH: The International Osteoporosis Foundation;2019.2. Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006; 17:1726–1733. PMID: 16983459.

Article3. Goel A, Chen Q, Chhatwal J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of generic pan-genotypic sofosbuvir/velpatasvir versus genotype-dependent direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018; 33:2029–2036. PMID: 29864213.4. Cheung CL, Ang SB, Chadha M, et al. An updated hip fracture projection in Asia: The Asian Federation of Osteoporosis Societies study. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2018; 4:16–21. PMID: 30775536.

Article5. Mithal A, Kaur P. Osteoporosis in Asia: a call to action. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2012; 10:245–247. PMID: 22898971.

Article6. Lim S, Koo BK, Lee EJ, et al. Incidence of hip fractures in Korea. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008; 26:400–405. PMID: 18600408.

Article7. National Institute on Aging. Korean longitudinal study of aging (KLoSA). 2019. cited by 2019 Feb 5. Available from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/resource/korean-longitudinal-study-aging-klosa.8. Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research, National Health Insurance Service. Osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracture fact sheet. Seoul: Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research, National Health Insurance Service;2018.9. Gold M. Demystifying ageing: Lifting the burden of fragility fractures and osteoporosis in Asia-Pacific. 2017. cited by 2018 Nov 27. Available from: https://perspectives.eiu.com/healthcare/demystifying-ageing-lifting-burden-fragility-fractures-and-osteoporosis-asia-pacific.10. Cha HB. Public policy on aging in Korea. Geriatr Gerontol. 2004; 4:S45–S48.

Article11. Ha YC, Kim HY, Jang S, et al. Economic burden of osteoporosis in South Korea: Claim data of the national health insurance service from 2008 to 2011. Calcif Tissue Int. 2017; 101:623–630. PMID: 28913546.

Article12. Kim J, Lee E, Kim S, et al. Economic burden of osteoporotic fracture of the elderly in South Korea: A national survey. Value Health Reg Issues. 2016; 9:36–41. PMID: 27881257.

Article13. World Health Organization. Active ageing: A policy framework. Geneva, CH: World Health Organization;2002.14. Kim S, So WY. Prevalence and correlates of fear of falling in Korean community-dwelling elderly subjects. Exp Gerontol. 2013; 48:1323–1328. PMID: 24001938.

Article15. Black DC. Working for a healthier tomorrow. London, UK: Crown Copyright;2008.16. Connolly MP, Kotsopoulos N, Postma MJ, et al. The fiscal consequences attributed to changes in morbidity and mortality linked to investments in health care: A Government perspective analytic framework. Value Health. 2017; 20:273–277. PMID: 28237208.

Article17. Mauskopf J, Standaert B, Connolly MP, et al. Economic analysis of vaccination programs: An ISPOR good practices for outcomes research task force report. Value Health. 2018; 21:1133–1149. PMID: 30314613.

Article18. Statistics Korea. Household income & expenditure trends in the third quarter 2016. 2016. cited by 2018 Nov 27. Available from: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=358731.19. International Monetary Fund. Interest rates, discount rate for Republic of Korea. 2019. cited by 2019 Feb 2. Available from: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/INTDSRKRM193N.20. Statistics Korea. Household assets, liabilities and income by age groups of households head. 2018. cited by 2018 Nov 27. Available from: http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1HDCA06&vw_cd=MT_ETITLE&list_id=&scrId=&seqNo=&language=en&obj_var_id=&itm_id=&conn_path=E3&path=%252Feng%252Fsearch%252Fsearch01_List.jsp.21. The Program on Global Aging, Health, and Policy, The Center for Economic and Social Research. Korean longitudinal study of aging. 2018. cited by 2018 Nov 27. Available from: https://g2aging.org/?section=study&studyid=5.22. National Pension Service. National pension statistics facts book. 2018. cited by 2018 Nov 27. Available from: https://www.nps.or.kr/jsppage/info/resources/info_resources_03_01.jsp?cmsId=statistics_year.23. Hyun KR, Kang S, Lee S. Population aging and healthcare expenditure in Korea. Health Econ. 2016; 25:1239–1251. PMID: 26085120.

Article24. Korea Ministry of Government Legislation. Korean laws in English: Value-added tax act. 2019. cited by 2018 Nov 27. Available from: http://www.moleg.go.kr/english/korLawEng.25. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Pensions at a glance 2017: OECD and G20 Indicators. Paris, FR: OECD Publishing;2017.26. Korea Legislation Research Institute. Statutes of the Republic of Korea. 2019. cited by 2018 Nov 27. Available from: http://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/main.do.27. Cho H, Byun JH, Song I, et al. Effect of improved medication adherence on health care costs in osteoporosis patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018; 97:e11470. PMID: 30045269.

Article28. Kwon JW, Park HY, Kim YJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pharmaceutical interventions to prevent osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women with osteopenia. J Bone Metab. 2016; 23:63–77. PMID: 27294078.

Article29. Alavinia SM, Burdorf A. Unemployment and retirement and ill-health: a cross-sectional analysis across European countries. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008; 82:39–45. PMID: 18264715.

Article30. Qu B, Ma Y, Yan M, et al. The economic burden of fracture patients with osteoporosis in western China. Osteoporos Int. 2014; 25:1853–1860. PMID: 24691649.

Article31. Schofield D, Shrestha RN, Zeppel MJB, et al. Economic costs of informal care for people with chronic diseases in the community: Lost income, extra welfare payments, and reduced taxes in Australia in 2015-2030. Health Soc Care Community. 2019; 27:493–501. PMID: 30378213.

Article32. Tatangelo G, Watts J, Lim K, et al. The cost of osteoporosis, osteopenia, and associated fractures in Australia in 2017. J Bone Miner Res. 2019; 34:616–625. PMID: 30615801.

Article33. Eekman DA, ter Wee MM, Coupe VM, et al. Indirect costs account for half of the total costs of an osteoporotic fracture: a prospective evaluation. Osteoporos Int. 2014; 25:195–204. PMID: 24072405.

Article34. Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, et al. Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA. 2009; 301:513–521. PMID: 19190316.

Article35. Lee YK, Jang S, Jang S, et al. Mortality after vertebral fracture in Korea: analysis of the National Claim Registry. Osteoporos Int. 2012; 23:1859–1865. PMID: 22109741.36. Kotsopoulos N, Connolly MP. Is the gap between micro- and macroeconomic assessments in health care well understood? The case of vaccination and potential remedies. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2014; 1:2.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Estimating the Socioeconomic Costs of Alcohol Drinking Among Adolescents in Korea

- Estimating the Economic Burden of Osteoporotic Vertebral Fracture among Elderly Korean Women

- Socioeconomic Costs of Glaucoma in Korea

- Socioeconomic Costs of Overactive Bladder and Stress Urinary Incontinence in Korea

- Socioeconomic Costs of Food-Borne Disease Using the Cost-of-Illness Model: Applying the QALY Method