Korean Circ J.

2019 Dec;49(12):1136-1151. 10.4070/kcj.2018.0413.

The Current Status of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Korea: Based on Year 2014 & 2016 Cohort of Korean Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (K-PCI) Registry

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Busan Paik Hospital, University of Inje College of Medicine, Busan, Korea.

- 4Department of Internal Medicine, St. Vincent's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, Suwon, Korea. cardiomoon@gmail.com

- 5Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 6Department of Cardiology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 7Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, Cheongju, Korea.

- 8Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Heart Center of Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju, Korea.

- 9Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Daegu, Korea.

- 10Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Sanggye-Paik Hospital, University of Inje College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 11Department of Cardiology, National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea.

- 12Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 13Department of Internal Medicine, Gangdong Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2464293

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2018.0413

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

In this second report from Korean percutaneous coronary intervention (K-PCI) registry, we sought to describe the updated information of PCI practices and Korean practice pattern of PCI (KP3).

METHODS

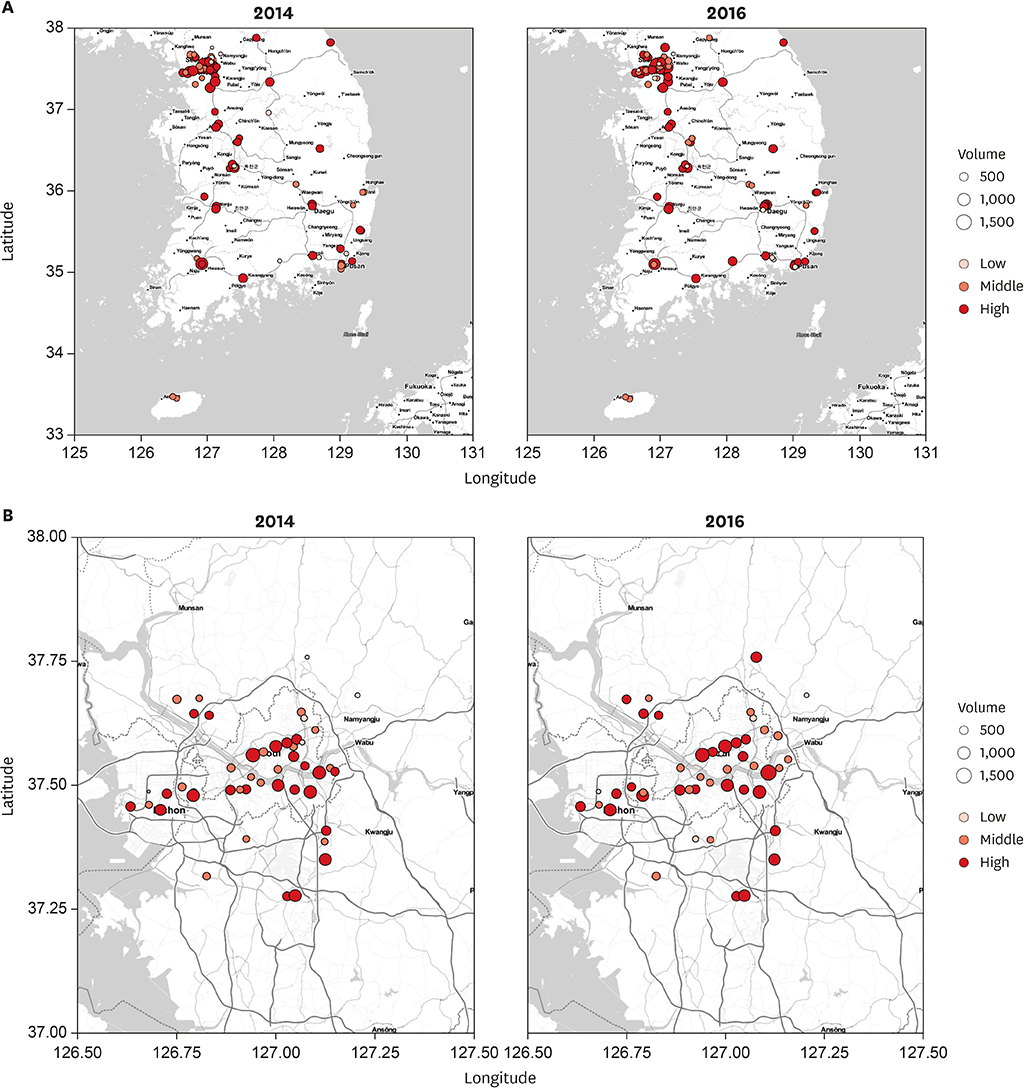

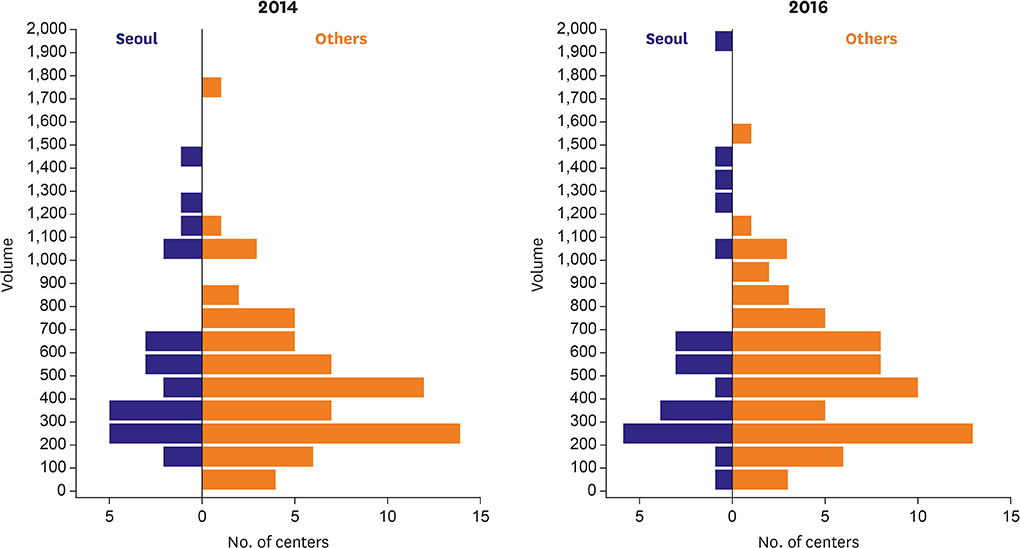

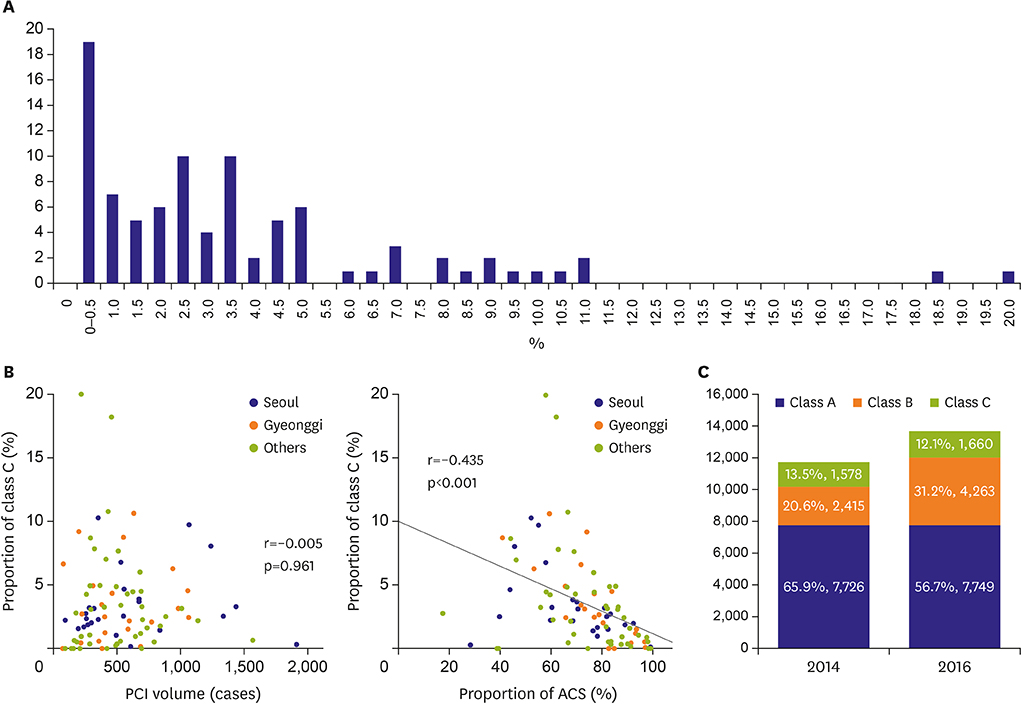

In addition to K-PCI registry of 2014, new cohort of 2016 from 92 participating centers was appended. Demographic and procedural information, as well as in-hospital outcomes, of PCI was collected using a web-based reporting system. KP3 class C was defined as any strategy with less evidence from randomized trials and more aggressive for PCI than medical therapy or bypass-surgery.

RESULTS

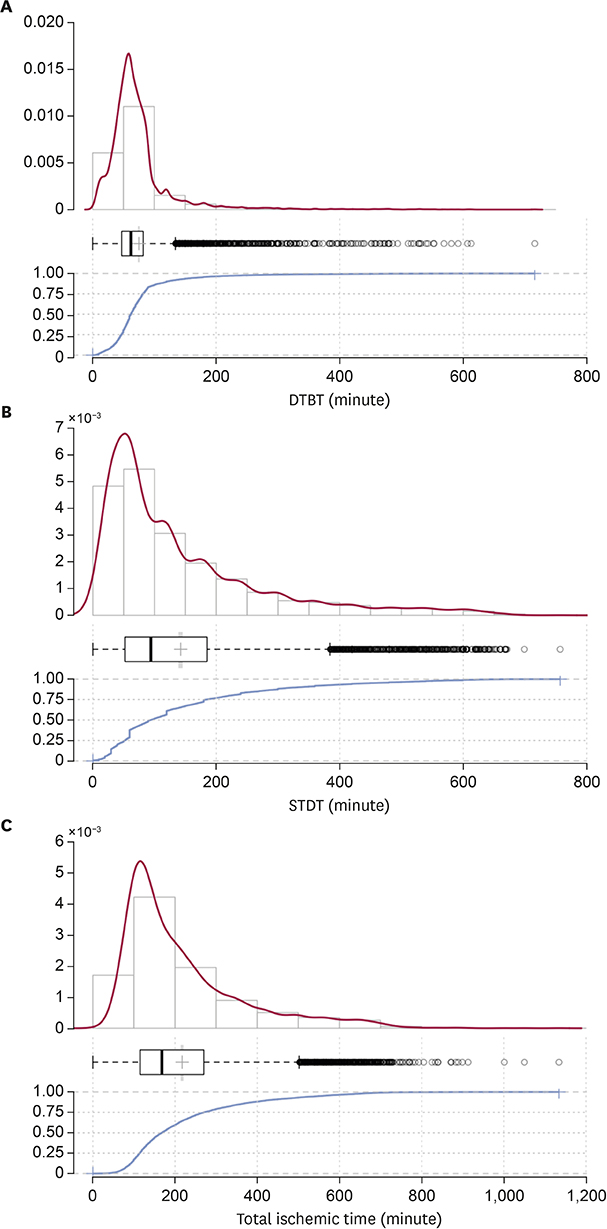

In 2016, total 48,823 PCI procedures were performed at 92 participating centers. Mean age of the patients was 65.7±11.6 years, and 71.7% were males. Overall patient characteristics and PCI practices in 2016 were similar to those in 2014. The biggest change was the decrease in the in-hospital occurrence of myocardial infarction (MI;1.6%→0.7%, p<0.001). Many associations between PCI volumes and demographic/procedural characteristics observed in 2014 have disappeared. The median of door-to-balloon time was 62 minutes, and 83.3% of ST-elevation MI patients received primary PCI within 90 minutes, while the median of total ischemic time was 168 minutes and patients who had total ischemic time within 120 and 180 minutes were 29.1% and 54.1%, respectively. The proportion of KP3 class C cases in non-acute coronary syndrome patients decreased from 13.5% in 2014 to 12.1% in 2016 (p<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

In this second report from K-PCI registry, we described the current practices of PCI and changes from 2014 to 2016 in Korea.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Jang JS, Han KR, Moon KW, et al. The current status of percutaneous coronary intervention in Korea: based on year 2014 cohort of Korean percutaneous coronary intervention (K-PCI) registry. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:328–340.2. Gwon HC, Jeon DW, Kang HJ, et al. The practice pattern of percutaneous coronary intervention in Korea: based on year 2014 cohort of Korean percutaneous coronary intervention (K-PCI) registry. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:320–327.

Article3. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992; 112:155–159.4. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. Converting among effect sizes. In : Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR, editors. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd;2009. p. 45–49.5. Mark DB, Lee KL, Harrell FE Jr. Understanding the role of P values and hypothesis tests in clinical research. JAMA Cardiol. 2016; 1:1048–1054.6. Durlak JA. How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009; 34:917–928.

Article7. Sullivan GM, Feinn R. Using effect size-or why the P value is not enough. J Grad Med Educ. 2012; 4:279–282.8. Masoudi FA, Ponirakis A, de Lemos JA, et al. Trends in U.S. cardiovascular care: 2016 report from 4 ACC national cardiovascular data registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:1427–1450.9. Mamas MA, Nolan J, de Belder MA, et al. Changes in arterial access site and association with mortality in the United Kingdom: observations from a national percutaneous coronary intervention database. Circulation. 2016; 133:1655–1667.10. Faxon DP, Williams DO. Interventional cardiology: current status and future directions in coronary disease and valvular heart disease. Circulation. 2016; 133:2697–2711.11. Kim C, Shin DH, Ahn CM, et al. The use pattern and clinical impact of new antiplatelet agents including prasugrel and ticagrelor on 30-day outcomes after acute myocardial infarction in Korea: Korean health insurance review and assessment data. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:888–897.12. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:2001–2015.

Article13. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1045–1057.14. Masoudi FA, Ponirakis A, Yeh RW, et al. Cardiovascular care facts: a report from the national cardiovascular data registry: 2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:1931–1947.15. Jneid H, Addison D, Bhatt DL, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC clinical performance and quality measures for adults with ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on performance measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 70:2048–2090.16. Denktas AE, Anderson HV, McCarthy J, Smalling RW. Total ischemic time: the correct focus of attention for optimal ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction care. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011; 4:599–604.17. Antman EM. Time is muscle: translation into practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 52:1216–1221.18. Shiomi H, Nakagawa Y, Morimoto T, et al. Association of onset to balloon and door to balloon time with long term clinical outcome in patients with ST elevation acute myocardial infarction having primary percutaneous coronary intervention: observational study. BMJ. 2012; 344:e3257.

Article19. Rollando D, Puggioni E, Robotti S, et al. Symptom onset-to-balloon time and mortality in the first seven years after STEMI treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2012; 98:1738–1742.20. Kim HK, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, et al. Relationship between time to treatment and mortality among patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention according to Korea acute myocardial infarction registry. J Cardiol. 2017; 69:377–382.

Article21. Bradley SM, Chan PS, Spertus JA, et al. Hospital percutaneous coronary intervention appropriateness and in-hospital procedural outcomes: insights from the NCDR. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012; 5:290–297.22. Han S, Park GM, Kim YG, et al. Trends, characteristics, and clinical outcomes of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in Korea between 2011 and 2015. Korean Circ J. 2018; 48:310–321.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Current Status of Coronary Intervention in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease

- Unprotected Left Main Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in a 108-Year-Old Patient

- The Second Report from K-PCI Registry: a Step toward Continuous Systemic Monitoring of Korean Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Practice

- Terrible Stent Thrombosis Induced by a Treadmill Test Performed Three Days after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- Simple Management of Radial Artery Perforation during Transradial Percutaneous Coronary Intervention