Korean J Gastroenterol.

2019 Sep;74(3):149-158. 10.4166/kjg.2019.74.3.149.

Importance of a Diversity Committee in Advancing the Korean Society of Gastroenterology: A Survey Analysis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea.

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea. nayoungkim49@empas.com

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, Eulji University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Internal Medicine, Catholic University of Daegu School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea.

- 5Department of Internal Medicine, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Korea.

- 6Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Guro Hospital, Korea.

- 7Department of Internal Medicine, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 8Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, Cheongju, Korea.

- KMID: 2458695

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4166/kjg.2019.74.3.149

Abstract

- BACKGROUND/AIMS

The numbers of women, young doctors, and foreigners in the medical field have increased continuously. On the other hand, the environment for these minority groups has not improved, particularly in Eastern countries. The authors aimed to increase the awareness of the importance of a Diversity Committee in the Korean Society of Gastroenterology (KSG) by an analysis of a survey.

METHODS

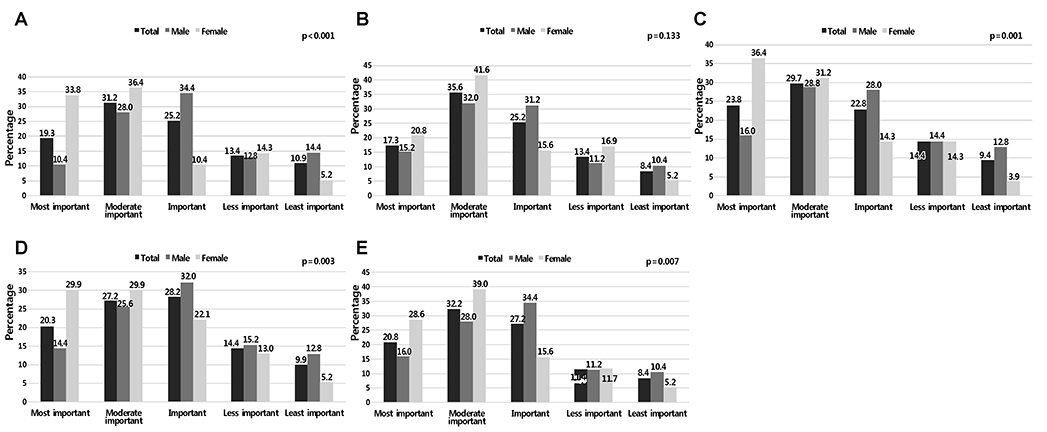

From January to February in 2019, a survey was conducted on physicians and a few medical students by googling. The questionnaire consisted of the target doctors of the Diversity Committee, purpose, specific activities, and expected effects of Diversity Committee to the KSG. The participants requested to respond with yes/no or a 5-point scale.

RESULTS

A total of 202 participants completed the questionnaire, and 93.5% (189/202) were medical specialists. The proportion of males was 61.9% (125/202), and 39.6% (80/202) and 36.1% (73/202) participants were in their 30s and 40s, respectively. A total of 174 participants (86.1%) agreed with the necessity of a Diversity Committee, and 180 participants (89.1%) answered this committee would help advance the KSG with significant differences between males and females (80.8% vs. 94.8%, p=0.006; 84.8% vs. 96.1%, p=0.011). Similarly, there were significant differences in the responses according to sex in most questions.

CONCLUSIONS

Most participants of the survey expected a contribution of the Diversity Committee to the advancement of the KSG. On the other hand, in most of the priorities of the target, purpose, specific activities, and expected effects of the Diversity Committee, there was a difference in the perceptions between males and females. Therefore, continuous efforts are needed to reduce the differences within the KSG.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

How Should the Diversity Committee Work?

Yong Sung Kim

Korean J Gastroenterol. 2019;74(3):127-129. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2019.74.3.127.

Reference

-

1. Chair's message of SNU diversity council. [Internet]. Seoul: SNU Diversity Council;2018. 07. cited 2019 Apr 10. Available from: http://diversity.snu.ac.kr/page/greeting.php.2. Inaugural forum: why diversity? [Internet]. Seoul: SNU Diversity Council;2016. 03. 28. cited 2019 June 3. Available from: http://diversity.snu.ac.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=forum_en&wr_id=1.3. Carethers JM, Quezada SM, Carr RM, Day LW. Diversity within US gastroenterology physician practices: the pipeline, cultural competencies, and gastroenterology societies approaches. Gastroenterology. 2019; 156:829–833.

Article4. Women Gastroenterologist Support Committee, the Japanese Society of Gastroenterology. Nagoshi S, Shiotani A, et al. Career advancement of women in the Japanese Society of Gastroenterology (JSGE). Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2013; 110:1387–1391.5. Member organizations of Korea federation of women's science & technology associations. [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Federation of Women's Science & Technology Associations;2019. 05. cited 2019 Jun 4. Available from: http://www.kofwst.org/eng/organizations/status.php.6. Underrepresented in medicine definition. [Internet]. Washington (DC): American Association of Medical Colleges;cited 2019 Apr 15. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/urm/.7. Kang SK, Kaplan S. Working toward gender diversity and inclusion in medicine: myths and solutions. Lancet. 2019; 393:579–586.

Article8. Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. academic medicine: statistics and medical school benchmarking 2003–2004. Washington (DC): Association of American Medical Colleges;2004. Table 1.9. More women than men enrolled in U.S. medical schools in 2017. [Internet]. Washington (DC): Association of American Medical Colleges;2017. 04. 18. Available from: https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-enrollment-2017/.10. Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. academic medicine: statistics and medical school benchmarking 2004–2005. Washington (DC): Association of American Medical Colleges;2005. Table 3.11. Association of American Medical Colleges. Women in U.S. academic medicine: statistics and medical school benchmarking 2004–2005. Washington (DC): Association of American Medical Colleges;2005. Table 2.12. The influence of women in medical circle has increased; a growing trend in women doctor and medical student. [Internet]. Seoul: Young Doctor Information, Inc.;2015. 04. 21. cited 2019 Apr 12. Available from: http://www.docdocdoc.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno= 173128.13. Yedidia MJ, Bickel J. Why aren't there more women leaders in academic medicine? The views of clinical department chairs. Acad Med. 2001; 76:453–465.

Article14. Mehta SJ, Forde KA. How to make a successful transition from fellowship to faculty in an academic medical center. Gastroenterology. 2013; 145:703–707.

Article15. Rice TK, Liu L, Jeffe DB, et al. Enhancing the careers of under-represented junior faculty in biomedical research: the Summer Institute Program to Increase Diversity (SIPID). J Natl Med Assoc. 2014; 106:50–57.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- How Should the Diversity Committee Work?

- The Effect of Aging on Intervals, Axis, Heart Position, and Transitional Zone of Electrocardiogram

- Food Diversity and Nutrient Intake of Elementary School Students in Daegu-Kyungbook Area

- An overview and the future of pediatric subspecialty board certification of the Korean Pediatric Society

- Research Using Big Data in Gastroenterology: Based on the Outcomes from Big Data Research Group of the Korean Society of Gastroenterology