Public Perceptions on Cancer Incidence and Survival: A Nation-wide Survey in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Family Medicine, Korean Cancer Center Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Family Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea. dwshin.snuh@gmail.com

- 3Cancer Survivorship Clinic, Seoul National University Cancer Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Laboratory of Health Promotion and Health Behavior, Biomedical Research Institute, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 5National Cancer Control Institute, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Korea. jonghyock@gmail.com

- 6Regional Cardiocerebrovascular Center, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea.

- 7Department of Health Informatics and Management, College of Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea.

- 8Graduate School of Health Science Business Convergence, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea.

- KMID: 2454356

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2014.369

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The aim of this study was to compare the public perceptions of the incidence rates and survival rates for common cancers with the actual rates from epidemiologic data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

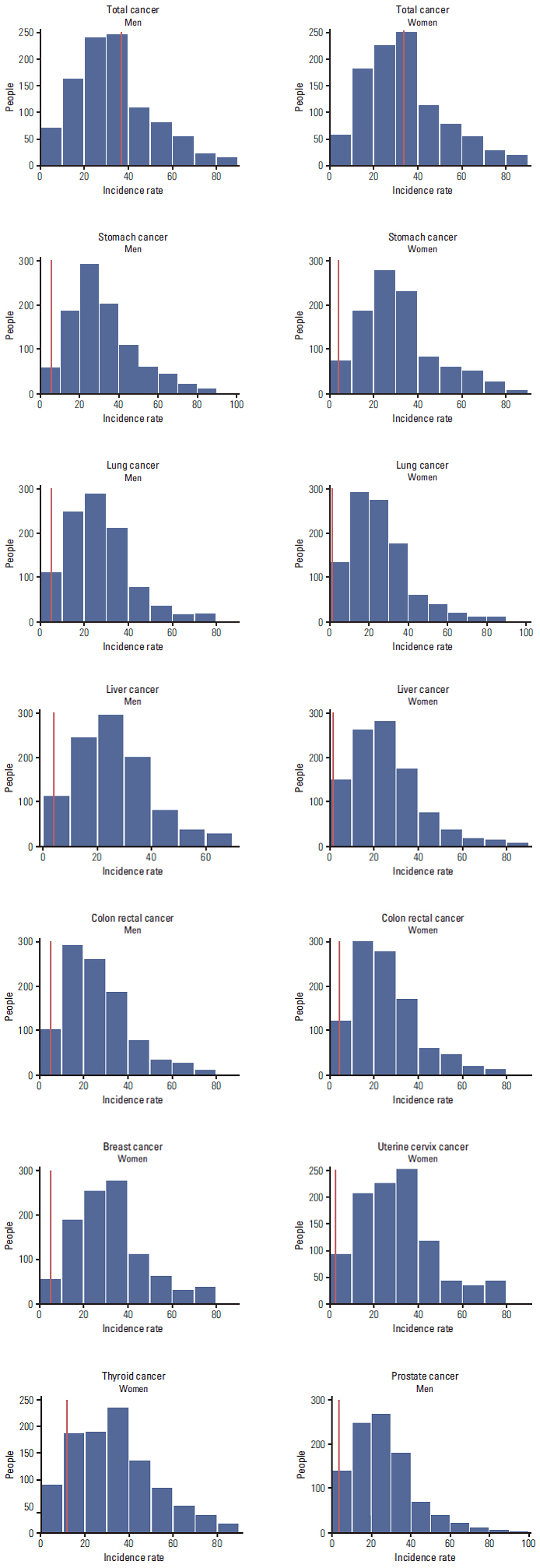

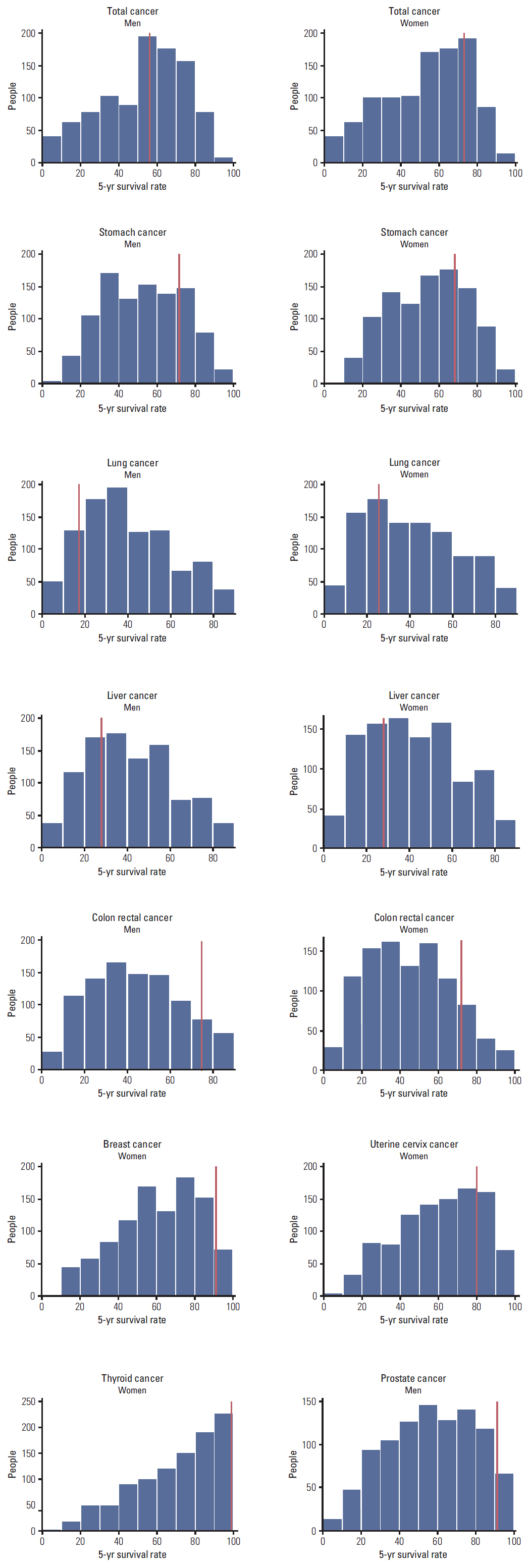

We conducted a survey of Korean adults without history of cancer (n=2,000). The survey consisted of questions about their perceptions regarding lifetime incidence rates and 5-year survival rates for total cancer, as well as those of eight site-specific cancers. To investigate associated factors, we included questions about cancer worry (Lerman's Cancer Worry Scale) or cared for a family member or friend with cancer as a caregiver.

RESULTS

Only 19% of Korean adults had an accurate perception of incidence rates compared with the epidemiologic data on total cancer. For specific cancers, most of the respondents overestimated the incidence rates and 10%-30% of men and 6%-18% of women had an accurate perception. A high score in "cancer worry" was associated with higher estimates of incidence rates in total and specific cancers. In cancers with high actual 5-year survival rates (e.g., breast and thyroid), the majority of respondents underestimated survival rates. However, about 50% of respondents overestimated survival rates in cancers with low actual survival rates (e.g., lung and liver). There was no factor consistently associated with perceived survival rates.

CONCLUSION

Widespread discrepancies were observed between perceived probability and actual epidemiological data. In order to reduce cancer worry and to increase health literacy, communication and patient education on appropriate risk is needed.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 4 articles

-

The Workplace Experiences of Breast Cancer Survivors: A Survey of an Online Community

Ka Ryeong Bae, Sun Young Kwon

Asian Oncol Nurs. 2016;16(4):208-216. doi: 10.5388/aon.2016.16.4.208.Health-Related Quality of Life, Perceived Social Support, and Depression in Disease-Free Survivors Who Underwent Curative Surgery Only for Prostate, Kidney and Bladder Cancer: Comparison among Survivors and with the General Population

Dong Wook Shin, Hyun Sik Park, Sang Hyub Lee, Seung Hyun Jeon, Seok Cho, Seok Ho Kang, Seung Chol Park, Jong Hyock Park, Jinsung Park

Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51(1):289-299. doi: 10.4143/crt.2018.053.Health-Related Quality of Life Changes in Prostate Cancer Patients after Radical Prostatectomy: A Longitudinal Cohort Study

Dong Wook Shin, Sang Hyub Lee, Tae-Hwan Kim, Seok Joong Yun, Jong Kil Nam, Seung Hyun Jeon, Seung Chol Park, Seung Il Jung, Jong-Hyock Park, Jinsung Park

Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51(2):556-567. doi: 10.4143/crt.2018.221.A Web-Based Decision Aid for Informed Prostate Cancer Screening: Development and Pilot Evaluation

Wonyoung Jung, In Young Cho, Keun Hye Jeon, Yohwan Yeo, Jae Kwan Jun, Mina Suh, Ansuk Jeong, Jungkwon Lee, Dong Wook Shin

J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(46):e360. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e360.

Reference

-

References

1. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2010. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute;2013.2. National Cancer Control Institute. National cancer registration and statistics in Korea 2011. Goyang: National Cancer Control Institute;2013.3. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Seo HG, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in 2010. Cancer Res Treat. 2013; 45:1–14.

Article4. Rastad H, Khanjani N, Khandani BK. Causes of delay in seeking treatment in patients with breast cancer in Iran: a qualitative content analysis study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012; 13:4511–5.

Article5. Borland R, Donaghue N, Hill D. Illnesses that Australians most feared in 1986 and 1993. Aust J Public Health. 1994; 18:366–9.

Article6. Donovan RJ, Jalleh G, Jones SC. The word 'cancer': reframing the context to reduce anxiety arousal. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2003; 27:291–3.

Article7. World Health Organization. Health literacy and health promotion, definitions, concepts and examples in the east Mediterranean region, 7th global conference on health promotion working paper [Internet]. Nairobi: WHO;2009. [cited 2014 Feb 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/7gchp/track2/en/last.8. Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005; 20:175–84.

Article9. Donelle L, Arocha JF, Hoffman-Goetz L. Health literacy and numeracy: key factors in cancer risk comprehension. Chronic Dis Can. 2008; 29:1–8.

Article10. Gardner PH, McMillan B, Raynor DK, Woolf E, Knapp P. The effect of numeracy on the comprehension of information about medicines in users of a patient information website. Patient Educ Couns. 2011; 83:398–403.

Article11. Morris NS, Field TS, Wagner JL, Cutrona SL, Roblin DW, Gaglio B, et al. The association between health literacy and cancer-related attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge. J Health Commun. 2013; 18 Suppl 1:223–41.

Article12. Jones CE, Maben J, Jack RH, Davies EA, Forbes LJ, Lucas G, et al. A systematic review of barriers to early presentation and diagnosis with breast cancer among black women. BMJ Open. 2014; 4:e004076.

Article13. Katapodi MC, Lee KA, Facione NC, Dodd MJ. Predictors of perceived breast cancer risk and the relation between perceived risk and breast cancer screening: a meta-analytic review. Prev Med. 2004; 38:388–402.

Article14. Whitaker KL, Simon AE, Beeken RJ, Wardle J. Do the British public recognise differences in survival between three common cancers? Br J Cancer. 2012; 106:1907–9.

Article15. Rutten LF, Hesse BW, Moser RP, McCaul KD, Rothman AJ. Public perceptions of cancer prevention, screening, and survival: comparison with state-of-science evidence for colon, skin, and lung cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2009; 24:40–8.16. Lerman C, Daly M, Masny A, Balshem A. Attitudes about genetic testing for breast-ovarian cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 1994; 12:843–50.

Article17. Paul C, Barratt A, Redman S, Cockburn J, Lowe J. Knowledge and perceptions about breast cancer incidence, fatality and risk among Australian women. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1999; 23:396–400.

Article18. Pohls UG, Fasching PA, Beck H, Kaufmann M, Kiechle M, von Minckwitz G, et al. Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with risk perception for breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2005; 14:1605–13.

Article19. Allahverdipour H, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Emami A. Breast cancer risk perception, benefits of and barriers to mammography adherence among a group of Iranian women. Women Health. 2011; 51:204–19.

Article20. Wardle J, Taylor T, Sutton S, Atkin W. Does publicity about cancer screening raise fear of cancer? Randomised trial of the psychological effect of information about cancer screening. BMJ. 1999; 319:1037–8.

Article21. Jones SC, Carter OB, Donovan RJ, Jalleh G. Western Australians' perceptions of the survivability of different cancers: implications for public education campaigns. Health Promot J Austr. 2005; 16:124–8.

Article22. Hakes JK, Viscusi WK. Dead reckoning: demographic determinants of the accuracy of mortality risk perceptions. Risk Anal. 2004; 24:651–64.

Article23. Takahashi M, Kai I, Muto T. Discrepancies between public perceptions and epidemiological facts regarding cancer prognosis and incidence in Japan: an Internet survey. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012; 42:919–26.

Article24. Reyna VF, Nelson WL, Han PK, Dieckmann NF. How numeracy influences risk comprehension and medical decision making. Psychol Bull. 2009; 135:943–73.

Article25. Consedine NS, Adjei BA, Ramirez PM, McKiernan JM. An object lesson: source determines the relations that trait anxiety, prostate cancer worry, and screening fear hold with prostate screening frequency. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008; 17:1631–9.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Chasm between Public Perceptions and Epidemiological Data on Colorectal Cancer

- Nation-Wide Korean Breast Cancer Data from 2008 Using the Breast Cancer Registration Program

- An Epidemiological Study on the Incidence of CO poisoning in Korea

- Disparities in All-cancer and Lung Cancer Survival by Social, Behavioral, and Health Status Characteristics in the United States: A Longitudinal Follow-up of the 1997-2015 National Health Interview Survey-National Death Index Record Linkage Study

- Cancer Registration in Korea: The Present and Furtherance