Terminal Versus Advanced Cancer: Do the General Population and Health Care Professionals Share a Common Language?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Family Medicine and Cancer Survivorship Clinic, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea. dwshin.snuh@gmail.com

- 2Laboratory of Health Promotion and Health Behavior, Biomedical Research Institute, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 3National Cancer Control Institute, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Korea. jonghyock@gmail.com

- 4Regional Cardiocerebrovascular Center, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju, Korea.

- 5Cancer Policy Branch, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Korea.

- 6Hospice and Palliative Care Branch, National Cancer Control Institute, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Korea.

- 7Institute on Aging, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 8Advanced Institutes of Convergence Technology, Seoul National University, Suwon, Korea.

- 9Department of Health Informatics and Management, College of Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea.

- 10Graduate School of Health Science Business Convergence, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea.

- KMID: 2454354

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2015.124

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Many end-of-life care studies are based on the assumption that there is a shared definition of language concerning the stage of cancer. However, studies suggest that patients and their families often misperceive patients' cancer stages and prognoses. Discrimination between advanced cancer and terminal cancer is important because the treatment goals are different. In this study, we evaluated the understanding of the definition of advanced versus terminal cancer of the general population and determined associated socio-demographic factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 2,000 persons from the general population were systematically recruited. We used a clinical vignette of a hypothetical advanced breast cancer patient, but whose cancer was not considered terminal. After presenting the brief history of the case, we asked respondents to choose the correct cancer stage from a choice of early, advanced, terminal stage, and don't know. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed to determine sociodemographic factors associated with the correct response, as defined in terms of medical context.

RESULTS

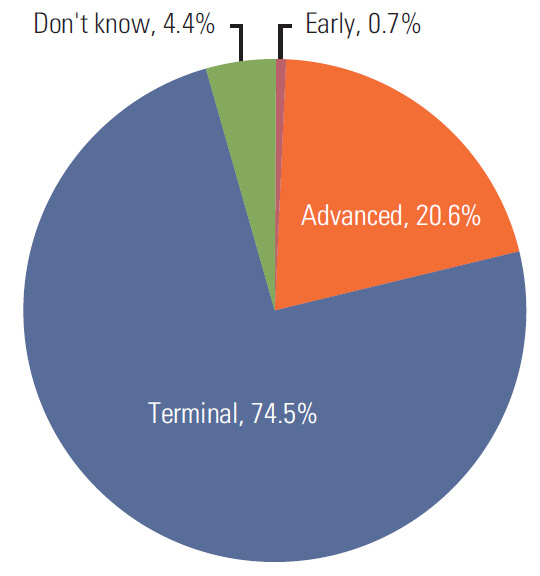

Only 411 respondents (20.6%) chose "advanced," while most respondents (74.5%) chose "terminal stage" as the stage of the hypothetical patient, and a small proportion of respondents chose "early stage" (0.7%) or "don't know" (4.4%). Multinomial logistic regression analysis found no consistent or strong predictor.

CONCLUSION

A large proportion of the general population could not differentiate advanced cancer from terminal cancer. Continuous effort is required in order to establish common and shared definitions of the different cancer stages and to increase understanding of cancer staging for the general population.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Consensus guidelines for the definition of the end stage of disease and last days of life and criteria for medical judgment

Sang-Min Lee, Su-Jung Kim, Youn Seon Choi, Dae Seog Heo, Sujin Baik, Bo Moon Choi, Daekyun Kim, Jae Young Moon, So Young Park, Yoon Jung Chang, In Cheol Hwang, Jung Hye Kwon, Sun-Hyun Kim, Yu Jung Kim, Jeanno Park, Ho Jung Ahn, Hyun Woo Lee, Ivo Kwon, Do-Kyong Kim, Ock-Joo Kim, Sang-Ho Yoo, Yoo Seock Cheong, Younsuck Koh

J Korean Med Assoc. 2018;61(8):509-521. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2018.61.8.509.Experiences and Opinions Related to End-of-Life Discussion: From Oncologists' and Resident Physicians' Perspectives

Su-Jin Koh, Shinmi Kim, JinShil Kim, Bhumsuk Keam, Dae Seog Heo, Kyung Hee Lee, Bong-Seog Kim, Jee Hyun Kim, Hye Jung Chang, Sun Kyung Baek

Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50(2):614-623. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.446.

Reference

-

References

1. Frosch DL, Kaplan RM. Shared decision making in clinical medicine: past research and future directions. Am J Prev Med. 1999; 17:285–94.

Article2. McCusker J. The terminal period of cancer: definition and descriptive epidemiology. J Chronic Dis. 1984; 37:377–85.

Article3. American Cancer Society. Advance directives: why do you need an advance directive? [Internet]. Mobile, AL: American Cancer Society;2015. [cited 2015 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/treatment/findingandpayingfortreatment/understandingfinancialandlegalmatters/advancedirectives/advance-directives-why-do-we-need-advance-directives.4. Christakis NA, Escarce JJ. Survival of medicare patients after enrollment in hospice programs. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:172–8.

Article5. Llobera J, Esteva M, Rifa J, Benito E, Terrasa J, Rojas C, et al. Terminal cancer. duration and prediction of survival time. Eur J Cancer. 2000; 36:2036–43.6. Levy MH, Back A, Benedetti C, Billings JA, Block S, Boston B, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009; 7:436–73.7. Swetz KM, Smith TJ. Palliative chemotherapy: when is it worth it and when is it not? Cancer J. 2010; 16:467–72.8. Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, Gallagher ER, Jackson VA, Lynch TJ, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29:2319–26.

Article9. Oh DY, Kim JE, Lee CH, Lim JS, Jung KH, Heo DS, et al. Discrepancies among patients, family members, and physicians in Korea in terms of values regarding the withholding of treatment from patients with terminal malignancies. Cancer. 2004; 100:1961–6.

Article10. Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, Dimitry S, Tattersall MH. Communicating prognosis in cancer care: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Oncol. 2005; 16:1005–53.

Article11. Shim HY, Park JH, Kim SY, Shin DW, Shin JY, Park BY, et al. Discordance between perceived and actual cancer stage among cancer patients in Korea: a nationwide survey. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e90483.

Article12. Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, Finkelman MD, Mack JW, Keating NL, et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367:1616–25.

Article13. Lux MP, Bayer CM, Loehberg CR, Fasching PA, Schrauder MG, Bani MR, et al. Shared decision-making in metastatic breast cancer: discrepancy between the expected prolongation of life and treatment efficacy between patients and physicians, and influencing factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013; 139:429–40.

Article14. Chow E, Andersson L, Wong R, Vachon M, Hruby G, Franssen E, et al. Patients with advanced cancer: a survey of the understanding of their illness and expectations from palliative radiotherapy for symptomatic metastases. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2001; 13:204–8.

Article15. Yun YH, Han KH, Park S, Park BW, Cho CH, Kim S, et al. Attitudes of cancer patients, family caregivers, oncologists and members of the general public toward critical interventions at the end of life of terminally ill patients. CMAJ. 2011; 183:E673–9.

Article16. Yun YH, Kwon YC, Lee MK, Lee WJ, Jung KH, Do YR, et al. Experiences and attitudes of patients with terminal cancer and their family caregivers toward the disclosure of terminal illness. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:1950–7.

Article17. Yun YH, Lee MK, Kim SY, Lee WJ, Jung KH, Do YR, et al. Impact of awareness of terminal illness and use of palliative care or intensive care unit on the survival of terminally ill patients with cancer: prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29:2474–80.18. Coalition to Transform Advanced Care. Public perceptions of advanced illness care: how can we talk when there’s no shared language? [Internet]. Washington, DC: Coalition to Transform Advanced Care;2012. [cited 2015 Aug 1]. Available from: http://advancedcarecoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Consumer-Research-Brief2.pdf.19. Lee JK, Yun YH, An AR, Heo DS, Park BW, Cho CH, et al. The understanding of terminal cancer and its relationship with attitudes toward end-of-life care issues. Med Decis Making. 2013; 34:720–30.

Article20. Mackillop WJ, Stewart WE, Ginsburg AD, Stewart SS. Cancer patients' perceptions of their disease and its treatment. Br J Cancer. 1988; 58:355–8.

Article21. Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, Walder S, Butow PN, Carrick S, et al. Discrepant perceptions about end-of-life communication: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007; 34:190–200.

Article22. Perkins HS. The varied understandings of "terminal cancer" and their implications for clinical research and patient care. Med Decis Making. 2014; 34:696–8.

Article23. Ahn E, Shin DW, Choi JY, Kang J, Kim DK, Kim H, et al. The impact of awareness of terminal illness on quality of death and care decision making: a prospective nationwide survey of bereaved family members of advanced cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2013; 22:2771–8.

Article24. Weeks JC, Cook EF, O'Day SJ, Peterson LM, Wenger N, Reding D, et al. Relationship between cancer patients' predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998; 279:1709–14.

Article25. Matsuyama R, Reddy S, Smith TJ. Why do patients choose chemotherapy near the end of life? A review of the perspective of those facing death from cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24:3490–6.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Impact of Clinical Nurses' Terminal Care Attitude and Spiritual Health on Their Terminal Care Stress

- The Effects of Attitude to Death in the Hospice and Palliative Professionals on Their Terminal Care Stress

- Needs of Hospice Care in Families of the Hospitalized Terminal Patients with Cancer

- Doctor's Perception and Referral Barriers toward Palliative Care for Advanced Cancer Patients

- Notification of Terminal Status and Advance Care Planning in Patients with Cancer