J Clin Neurol.

2019 Jul;15(3):376-385. 10.3988/jcn.2019.15.3.376.

Examining the Impact of Refractory Myasthenia Gravis on Healthcare Resource Utilization in the United States: Analysis of a Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Patient Registry Sample

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Health Care Organization and Policy, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA.

- 2Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Boston, MA, USA.

- 3Department of Biostatistics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA. caban@uab.edu

- KMID: 2451123

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2019.15.3.376

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Patients with refractory myasthenia gravis (MG) experience ongoing disease burden that might be reflected in their healthcare utilization. Here we examine the impact of refractory MG on healthcare utilization.

METHODS

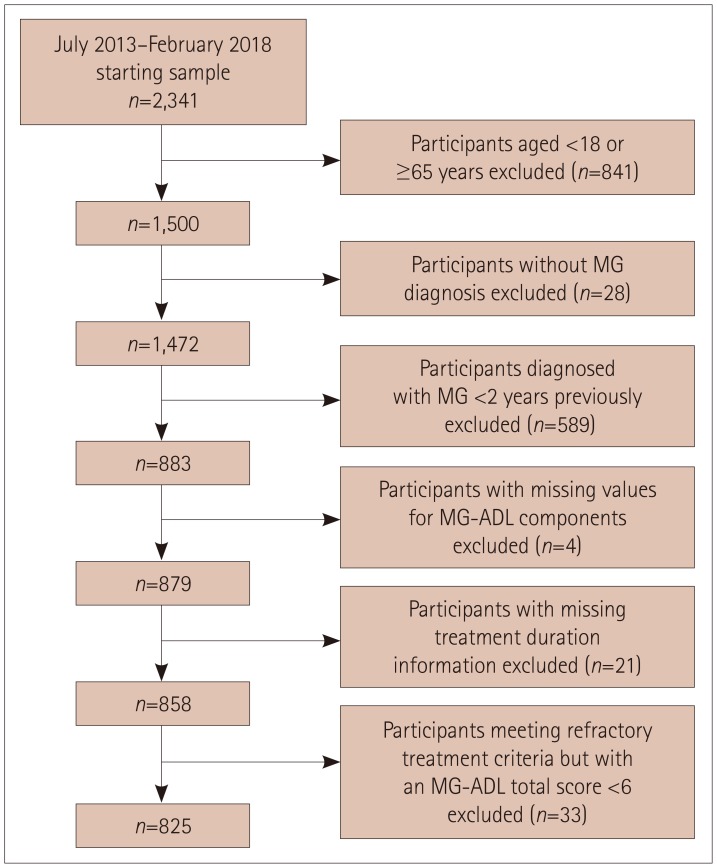

The 825 included participants were aged 18-64 years, enrolled in the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Patient Registry between July 2013 and February 2018, and had been diagnosed with MG ≥2 years previously.

RESULTS

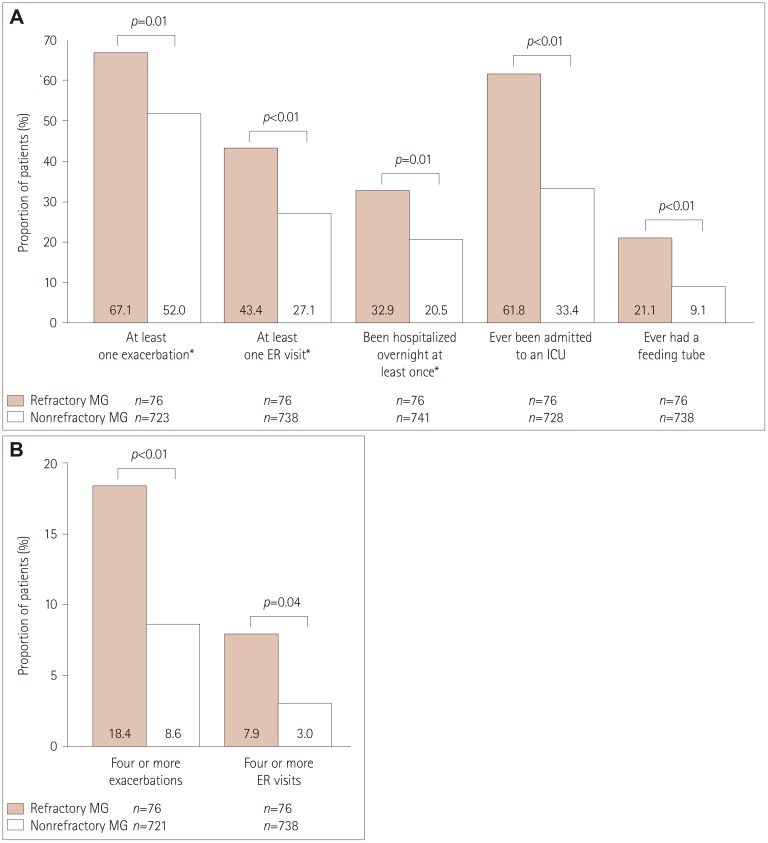

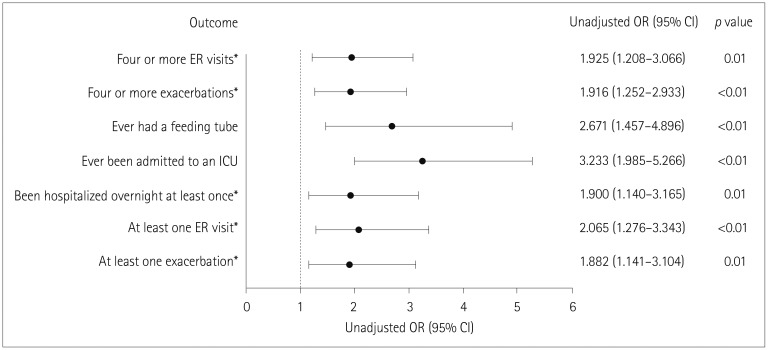

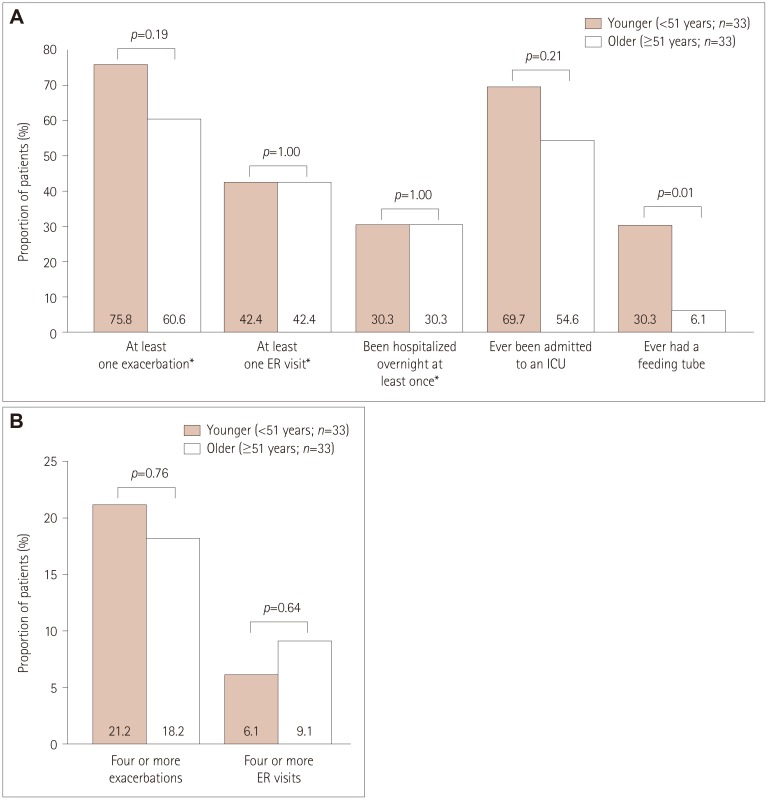

Participants comprised 76 (9.2%) with refractory MG and 749 (90.8%) with nonrefractory MG. During the 6 months before enrollment, participants with refractory MG were significantly more likely than those with nonrefractory MG to have experienced at least one exacerbation [67.1% vs. 52.0%, respectively, p=0.01; odds ratio (OR)=1.882, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.141-3.104], visited an emergency room at least once [43.4% vs. 27.1%, p<0.01; OR=2.065, 95% CI=1.276-3.343], been hospitalized overnight at least once (32.9% vs. 20.5%, p=0.01; OR=1.900, 95% CI=1.140-3.165), ever been admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) (61.8% vs. 33.4%, p<0.01; OR=3.233, 95% CI=1.985-5.266), or ever required a feeding tube (21.1% vs. 9.1%, p<0.01; OR=2.671, 95% CI=1.457-4.896). A total of 75.8% younger females with refractory disease (<51 years, n=33) experienced at least one exacerbation, 69.7% had been admitted to an ICU, and 30.3% had required a feeding tube. For older females with refractory disease (≥51 years, n=33), 60.6%, 54.6%, and 6.1% experienced these outcomes, respectively (between-group differences were not significant).

CONCLUSIONS

Refractory MG is associated with higher disease burden and healthcare utilization than nonrefractory MG.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Heldal AT, Owe JF, Gilhus NE, Romi F. Seropositive myasthenia gravis: a nationwide epidemiologic study. Neurology. 2009; 73:150–151. PMID: 19597135.

Article2. Fang F, Sveinsson O, Thormar G, Granqvist M, Askling J, Lundberg IE, et al. The autoimmune spectrum of myasthenia gravis: a Swedish population-based study. J Intern Med. 2015; 277:594–604. PMID: 25251578.

Article3. Cetin H, Fülöp G, Zach H, Auff E, Zimprich F. Epidemiology of myasthenia gravis in Austria: rising prevalence in an ageing society. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012; 124:763–768. PMID: 23129486.

Article4. Park SY, Lee JY, Lim NG, Hong YH. Incidence and prevalence of myasthenia gravis in Korea: a population-based study using the National Health Insurance claims database. J Clin Neurol. 2016; 12:340–344. PMID: 27165426.

Article5. Murai H, Yamashita N, Watanabe M, Nomura Y, Motomura M, Yoshikawa H, et al. Characteristics of myasthenia gravis according to onset-age: Japanese nationwide survey. J Neurol Sci. 2011; 305:97–102. PMID: 21440910.

Article6. Grob D, Brunner N, Namba T, Pagala M. Lifetime course of myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2008; 37:141–149. PMID: 18059039.

Article7. Robertson NP, Deans J, Compston DA. Myasthenia gravis: a population based epidemiological study in Cambridgeshire, England. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998; 65:492–496. PMID: 9771771.

Article8. Melzer N, Ruck T, Fuhr P, Gold R, Hohlfeld R, Marx A, et al. Clinical features, pathogenesis, and treatment of myasthenia gravis: a supplement to the Guidelines of the German Neurological Society. J Neurol. 2016; 263:1473–1494. PMID: 26886206.

Article9. Zieda A, Ravina K, Glazere I, Pelcere L, Naudina MS, Liepina L, et al. A nationwide epidemiological study of myasthenia gravis in Latvia. Eur J Neurol. 2018; 25:519–526. PMID: 29194859.

Article10. Muppidi S, Wolfe GI, Conaway M, Burns TM. MG Composite and MG-QoL15 Study Group. MG-ADL: still a relevant outcome measure. Muscle Nerve. 2011; 44:727–731. PMID: 22006686.

Article11. Hoffmann S, Ramm J, Grittner U, Kohler S, Siedler J, Meisel A. Fatigue in myasthenia gravis: risk factors and impact on quality of life. Brain Behav. 2016; 6:e00538. PMID: 27781147.

Article12. Paul RH, Cohen RA, Goldstein JM, Gilchrist JM. Fatigue and its impact on patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2000; 23:1402–1406. PMID: 10951443.

Article13. Silvestri NJ, Wolfe GI. Treatment-refractory myasthenia gravis. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2014; 15:167–178. PMID: 24872217.

Article14. Wendell LC, Levine JM. Myasthenic crisis. Neurohospitalist. 2011; 1:16–22. PMID: 23983833.

Article15. Conti-Fine BM, Milani M, Kaminski HJ. Myasthenia gravis: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest. 2006; 116:2843–2854. PMID: 17080188.

Article16. Sanders DB, Wolfe GI, Benatar M, Evoli A, Gilhus NE, Illa I, et al. International consensus guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: executive summary. Neurology. 2016; 87:419–425. PMID: 27358333.17. Suh J, Goldstein JM, Nowak RJ. Clinical characteristics of refractory myasthenia gravis patients. Yale J Biol Med. 2013; 86:255–260. PMID: 23766745.18. Mantegazza R, Antozzi C. When myasthenia gravis is deemed refractory: clinical signposts and treatment strategies. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018; 11:1756285617749134. PMID: 29403543.

Article19. Boldingh MI, Dekker L, Maniaol AH, Brunborg C, Lipka AF, Niks EH, et al. An up-date on health-related quality of life in myasthenia gravis-results from population based cohorts. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015; 13:115. PMID: 26232146.

Article20. Utsugisawa K, Suzuki S, Nagane Y, Masuda M, Murai H, Imai T, et al. Health-related quality-of-life and treatment targets in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2014; 50:493–500. PMID: 24536040.

Article21. Engel-Nitz NM, Boscoe A, Wolbeck R, Johnson J, Silvestri NJ. Burden of illness in patients with treatment refractory myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2018; 58:99–105.

Article22. Murai H, Hasebe M, Murata T, Utsugisawa K. Clinical burden and healthcare resource utilization associated with myasthenia gravis: assessments from a Japanese claims database. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2019; 10:61–68.

Article23. Wolfe GI, Herbelin L, Nations SP, Foster B, Bryan WW, Barohn RJ. Myasthenia gravis activities of daily living profile. Neurology. 1999; 52:1487–1489. PMID: 10227640.

Article24. Howard JF Jr, Utsugisawa K, Benatar M, Murai H, Barohn RJ, Illa I, et al. Safety and efficacy of eculizumab in anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive refractory generalised myasthenia gravis (REGAIN): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2017; 16:976–986. PMID: 29066163.25. Lee I, Kaminski HJ, Xin H, Cutter G. Gender and quality of life in myasthenia gravis patients from the myasthenia gravis foundation of America registry. Muscle Nerve. 2018; 58:90–98.

Article26. Gilhus NE, Nacu A, Andersen JB, Owe JF. Myasthenia gravis and risks for comorbidity. Eur J Neurol. 2015; 22:17–23. PMID: 25354676.

Article27. Diaz BC, Flores-Gavilán P, García-Ramos G, Lorenzana-Mendoza NA. Myasthenia gravis and its comorbidities. J Neurol Neurophysiol. 2015; 6:1–5. PMID: 26753104.

Article28. Tanovska N, Novotni G, Sazdova-Burneska S, Kuzmanovski I, Boshkovski B, Kondov G, et al. Myasthenia gravis and associated diseases. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018; 6:472–478. PMID: 29610603.

Article29. Guptill JT, Marano A, Krueger A, Sanders DB. Cost analysis of myasthenia gravis from a large U.S. insurance database. Muscle Nerve. 2011; 44:907–911. PMID: 22102461.

Article30. Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, Robbins JA. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract. 2000; 49:147–152. PMID: 10718692.