J Dent Rehabil Appl Sci.

2019 Mar;35(1):27-36. 10.14368/jdras.2019.35.1.27.

The survey on the infection control of noncritical instruments used in dental treatment

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Prosthodontics, College of Dentistry, Wonkwang University, Iksan, Republic of Korea. dentist@empas.com

- KMID: 2450923

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14368/jdras.2019.35.1.27

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The aims of this study were to evaluate the dentist's awareness and the actual status of infection control of noncritical dental instruments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

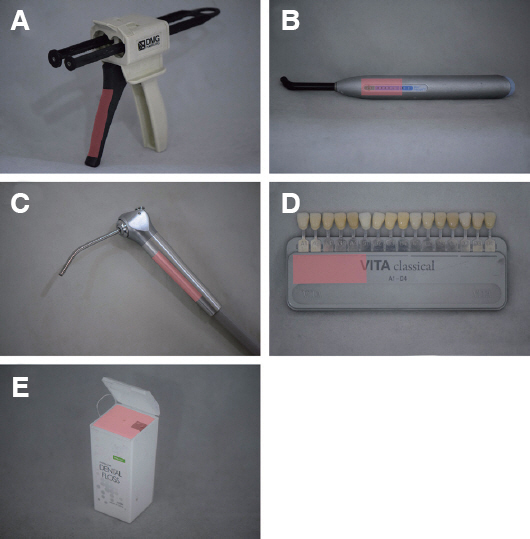

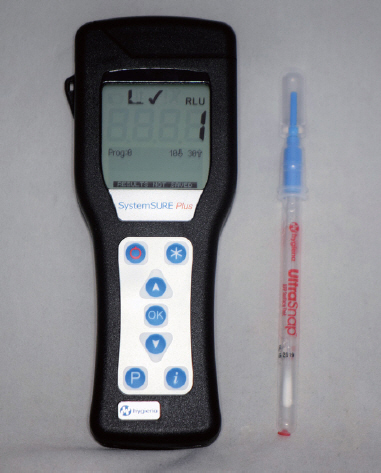

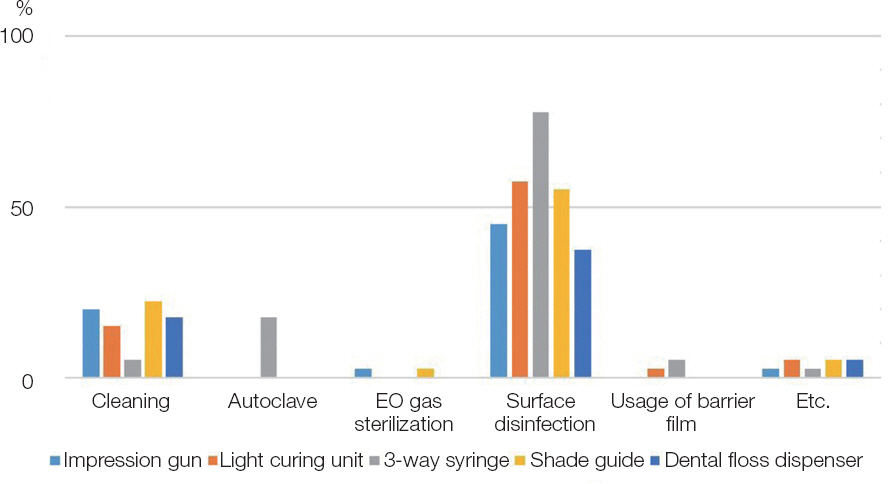

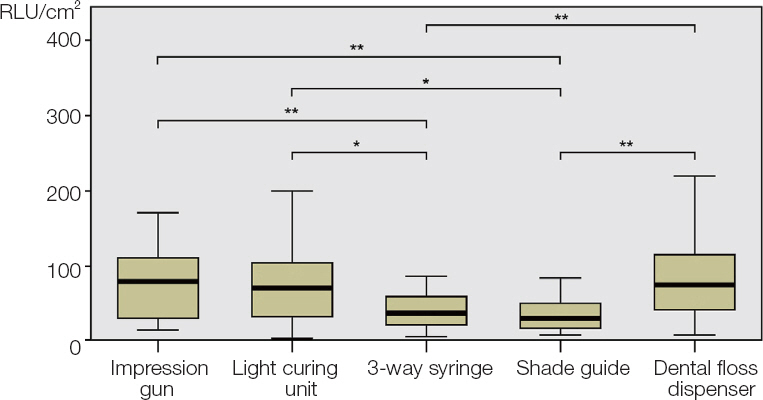

40 dental clinics in Daejeon, South Chungcheong, North Chungcheong and North Jeolla provinces were surveyed. The questionnaire was delivered to the dentists belonging to those clinics, and the awareness and the practice of infection control were examined. The microbial contamination on the surface of five noncritical instruments (impression gun, light curing unit, 3-way syringe, shade guide, and dental floss dispenser) used by them was measured with an ATP luminometer. Correlation analysis between the awareness and the actual state of infection control was conducted.

RESULTS

Awareness and frequency of infection control was highest in the 3-way syringe. Surface disinfection using disinfectant was most frequent in all instruments. 3-way syringes and shade guides were less contaminated than impression guns, light curing units, and dental floss dispensers.

CONCLUSION

3-way syringes had a significant correlation between user awareness of infection control and surface contamination, and the higher awareness, the lower the contamination measurement was shown.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Korea Centers for Disease Control &Prevention (KCDC). Guidelines for prevention and control of healthcare associated infections. 2017. (updated 2019 Mar 4). Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/together/CdcKrTogether0302.jsp?menuIds=HOME006-NU2804-NU3027-MNU2979&fid=10713&q_type=&q_value=&cid=138061&pageNum=1.2. Bolyard EA, Tablan OC, Williams WW, Pearson ML, Shapiro CN, Deitchmann SD. Guideline for infection control in healthcare personnel, 1998. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1998; 19:407–63. DOI: 10.2307/30142429. PMID: 9669622.3. Lee JH. The infection control of dental impressions. J Dent Rehabil Appl Sci. 2013; 29:183–93. DOI: 10.14368/jdras.2013.29.2.183.4. KOSIS (Korean Statistical Information Service). 2018 Statistics on the aged. Available from: http://kosis.kr/publication/publicationWord.do. (updated 2019 Mar 4).5. Meskin L, Berg R. Impact of older adults on private dental practices, 1988-1998. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000; 131:1188–95. DOI: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0356. PMID: 10953537.6. Younai FS. Health care-associated transmission of hepatitis B &C viruses in dental care (dentistry). Clin Liver Dis. 2010; 14:93–104. DOI: 10.1016/j.cld.2009.11.010. PMID: 20123443.7. Spaulding EH. Lawrence C, Block SS, editors. Chemical disinfection of medical and surgical materials. Disinfection, sterilization and preservation. Philadelphia: Lea &Febiger;1968. p. 517–31.8. American Dental Association Council (ADA). Infection control recommendations for the dental office and the dental laboratory. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996; 127:672–80. DOI: 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0280.9. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings. MMWR (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep). 2003; 52:1–61. PMID: 14685139.10. Kim HK, Lee SJ. The control of transmissible disease in dental practice in Seoul, Korea. J Korean Dent Assoc. 1995; 33:291–6.11. Lee YA, Jo MJ, Bae JY, Park HS. A study on practice of infection control among dental staffs in dental office. J Dent Hyg Sci. 2007; 7:263–9.12. Kim KM, Jung JY, Hwang YS. A study on the state of infection control in dental clinic. J Korean Acad Dental Hygiene Education. 2007; 7:213–30.13. Jeon HS, Lee JH. The study of awareness and practice of infection control on dental practitioners during the prosthodontic treatment. J Korean Acad Prosthodont. 2015; 53:189–97. DOI: 10.4047/jkap.2015.53.3.189.14. Kim K. Likert scale. Korean J Fam Med. 2011; 32:1–2. DOI: 10.4082/kjfm.2011.32.1.1.15. Goebel WM. Reliability of the medical history in identifying patients likely to place dentists at an increased hepatitis risk. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979; 98:907–13. DOI: 10.14219/jada.archive.1979.0192. PMID: 287709.16. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Recommendations for prevention of HIV transmission in healthcare settings. MMWR (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep). 1987; 36:1–18.17. Garner JS, Favero MS. CDC guideline for handwashing and hospital environmental control, 1985. Infect Control. 1986; 7:231–43. DOI: 10.1017/S0195941700084022.18. Korean Dental Association (KDA). Infection control procedure in dental office. Available from: https://www.kda.or.kr/downLoad.kda?attach_key=5156&save_attach_name=201605251464143729427021.pdf. (updated 2019 Mar d4).19. Cha SR, Kim KJ. Protocol for disinfection and sterilization in dental clinic. J Korean Dent Assoc. 2013; 51:130–7.20. Runnells RR. An overview of infection control in dental practice. J Prosthet Dent. 1988; 59:625–9. DOI: 10.1016/0022-3913(88)90083-2.21. Boyce JM, Havill NL, Dumigan DG, Golebiewski M, Balogun O, Rizvani R. Monitoring the effectiveness of hospital cleaning practices by use of an adenosine triphosphate bioluminescence assay. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009; 30:678–84. DOI: 10.1086/598243. PMID: 19489715.22. Hygiena LLC. SystemSURE Operators Manual V3.0. 2013. Available from: https://www.hygiena.com/food-and-beverage-products/systemsure.html#resources. (updated 2019 Mar4).23. Davidson CA, Griffith CJ, Peters AC, Fielding LM. Evaluation of two methods for monitoring surface cleanliness-ATP bioluminescence and traditional hygiene swabbing. Luminescence. 1999; 14:33–8. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-7243(199901/02)14:1<33::AID-BIO514>3.0.CO;2-I. PMID: 10398558.24. Smith PW, Gibbs S, Sayles H, Hewlett A, Rupp ME, Iwen PC. Observations on hospital room contamination testing. Healthc Infect. 2013; 18:10–3. DOI: 10.1071/HI12049.25. Huang YS, Chen YC, Chen ML, Cheng A, Hung IC, Wang JT, Sheng WH, Chang SC. Comparing visual inspection, aerobic colony counts, and adenosine triphosphate bioluminescence assay for evaluating surface cleanliness at a medical center. Am J Infect Control. 2015; 43:882–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.03.027. PMID: 25952617.26. Westergard EJ, Romito LM, Kowolik MJ, Palenik CJ. Controlling bacterial contamination of dental impression guns. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011; 142:1269–74. DOI: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0112. PMID: 22041413.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Actual Condition and an Alternative of Students in the Department of Dental Hygiene about Dental Instrument Injuries during Clinical Practice

- The Analysis of Actual Condition for Implementation of Dental Clinic Infection Prevention Standards in the Hospital

- Effects of Infection Control Training on Dental Hygienists' Health Beliefs and Practices of Infection Control

- Pre-Treatment Infection Control Practices and Associated Factors among Korean Dental Hygienists in Response to COVID-19

- The study of awareness and practice of infection control on dental practitioners during the prosthodontic treatment