J Korean Med Sci.

2017 Aug;32(8):1319-1326. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.8.1319.

Trends in Fetal and Perinatal Mortality in Korea (2009–2014): Comparison with Japan and the United States

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Konyang University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea. limsoa@hanmail.net

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Konyang University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea.

- 3Department of Pediatrics, Kyung Hee University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2439467

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.8.1319

Abstract

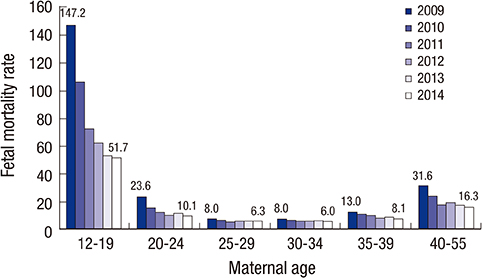

- Fetal death is an important indicator of national health care. In Korea, the fetal mortality rate is likely to increase due to advanced maternal age and multiple births, but there is limited research in this field. The authors investigated the characteristics of fetal deaths, the annual changes in the fetal mortality rate and the perinatal mortality rate in Korea, and compared them with those in Japan and the United States. Fetal deaths were restricted to those that occurred at 20 weeks of gestation or more. From 2009 to 2014, the overall mean fetal mortality rate was 8.5 per 1,000 live births and fetal deaths in Korea, 7.1 in Japan and 6.0 in the United States. While the birth rate in Korea declined by 2.1% between 2009 and 2014, the decrease in the number of fetal deaths was 34.5%. The fetal mortality rate in Korea declined by 32.9%, from 11.0 in 2009 to 7.4 in 2014, the largest decline among the 3 countries. In addition, rates for receiving prenatal care increased from 53.9% in 2009 to 75.0% in 2014. Perinatal mortality rate I and II were the lowest in Japan, followed by Korea and the United States, and Korea showed the greatest decrease in rate of perinatal mortality rate II. In this study, we identified that the indices of fetal deaths in Korea are improving rapidly. In order to maintain this trend, improvement of perinatal care level and stronger national medical support policies should be maintained continuously.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Neonatal and perinatal mortality: country, regional and global estimates [Internet]. accessed on 26 March 2017. Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43444/1/9241563206_eng.pdf.2. Cousens S, Blencowe H, Stanton C, Chou D, Ahmed S, Steinhardt L, Creanga AA, Tunçalp O, Balsara ZP, Gupta S, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2009 with trends since 1995: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011; 377:1319–1330.3. MacDorman MF, Gregory EC. Fetal and perinatal mortality: United States, 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015; 64:1–24.4. Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing Group. Causes of death among stillbirths. JAMA. 2011; 306:2459–2468.5. Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, Frøen JF, Smith GC, Gibbons K, Coory M, Gordon A, Ellwood D, McIntyre HD, et al. Major risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011; 377:1331–1340.6. Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing Group. Association between stillbirth and risk factors known at pregnancy confirmation. JAMA. 2011; 306:2469–2479.7. Liu S, Joseph KS, Wen SW. Trends in fetal and infant deaths caused by congenital anomalies. Semin Perinatol. 2002; 26:268–276.8. Ministry of Health and Welfare (KR). National Survey on Trends of Induced Abortion. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2011.9. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (JP). Vital statistics: foetal mortality [Internet]. accessed on 31 March 2017. Available at http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/NewListE.do?tid=000001028897.10. Shim JW, Jin HS, Bae CW. Changes in survival rate for very-low-birth-weight infants in Korea: comparison with other countries. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30:S25–S34.11. Chang JY, Lee KS, Hahn WH, Chung SH, Choi YS, Shim KS, Bae CW. Decreasing trends of neonatal and infant mortality rates in Korea: compared with Japan, USA, and OECD nations. J Korean Med Sci. 2011; 26:1115–1123.12. Choi SH, Park YS, Shim KS, Choi YS, Chang JY, Hahn WH, Bae CW. Recent trends in the incidence of multiple births and its consequences on perinatal problems in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2010; 25:1191–1196.13. Han DH, Lee KS, Chung SH, Choi YS, Hahn WH, Chang JY, Bae CW. Decreasing pattern in perinatal mortality rates in Korea: in comparison with OECD nations. Korean J Perinatol. 2011; 22:209–220.14. MicroData Integrated Service (KR). Complementary investigation of cause of death [Internet]. accessed on 31 March 2017. Available at https://mdis.kostat.go.kr/index.do.15. MicroData Integrated Service (KR). Population dynamics database: birth [Internet]. accessed on 31 March 2017. Available at https://mdis.kostat.go.kr/index.do.16. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (JP). Vital statistics: natality [Internet]. accessed on 31 March 2017. Available at http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/NewListE.do?tid=000001028897.17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). National center for health statistics: birth data files [Internet]. accessed on 31 March 2017. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/vitalstatsonline.htm.18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). National center for health statistics: fetal death data files [Internet]. accessed on 31 March 2017. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/vitalstatsonline.htm.19. Health Insurance review & Assessment Service (KR). Healthcare bigdata hub [Internet]. accessed on 31 March 2017. Available at http://opendata.hira.or.kr/op/opc/olap4thDsInfo.do.20. Ministry of Health and Welfare (KR). Health management support project for mother and newborn 2017. [Internet]. accessed on 31 March 2017. Available at http://www.socialservice.or.kr/upload/etc/2017_3000.pdf.21. Ministry of Health and Welfare (KR). Establishment of Health Care Delivery System between the Integrated Center for High-risk Pregnant Women and Neonates and the Maternity Care in the Underserved Area. Cheongju: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2015.22. Ministry of Health and Welfare (KR). Evaluation of Performance and Efficiency in Operation of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, 2016. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2016.23. Kim HY, Moon CS. Integrated care center for high risk pregnancy and neonate: an analysis of process and problems in obstetrics. Korean J Perinatol. 2014; 25:140–152.24. Chang YS, Park HY, Park WS. The Korean neonatal network: an overview. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30:S3–S11.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Recent Trends in Neonatal Mortality in Very Low Birth Weight Korean Infants: In Comparison with Japan and the USA

- Decreasing Trends of Neonatal and Infant Mortality Rates in Korea: Compared with Japan, USA, and OECD Nations

- Bench-marking of Japanese Perinatal Center System for Improving Maternal and Neonatal Outcome in Korea

- Infant, maternal, and perinatal mortality statistics in the Republic of Korea, 2014

- Perinatal Care Center System for High Risk Pregnancy and Newborn in Japan