Infect Chemother.

2018 Dec;50(4):319-327. 10.3947/ic.2018.50.4.319.

Elimination of Lancet-Related Needlestick Injuries Using a Safety-Engineered Lancet: Experience in a Hospital

- Affiliations

-

- 1Infection Control Office, Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. hswon1@snu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Boramae Medical Center and Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2429935

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3947/ic.2018.50.4.319

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Lancet-related needlestick injuries (NSIs) occur steadily in clinical practices. Safety-engineered devices (SEDs) can systematically reduce NSIs. However, the use of SEDs is not active and no study to guide the implementation of SEDs was known in South Korea. The lancet-related NSIs may be eliminated to zero incidence using a SED lancet with effective sharp injury protection and reuse prevention features.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

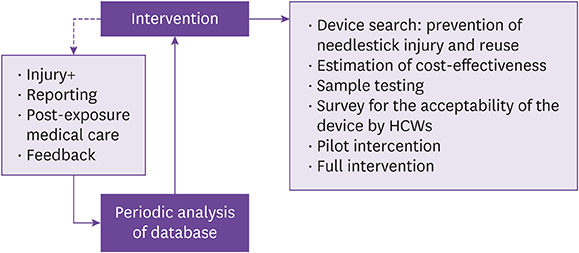

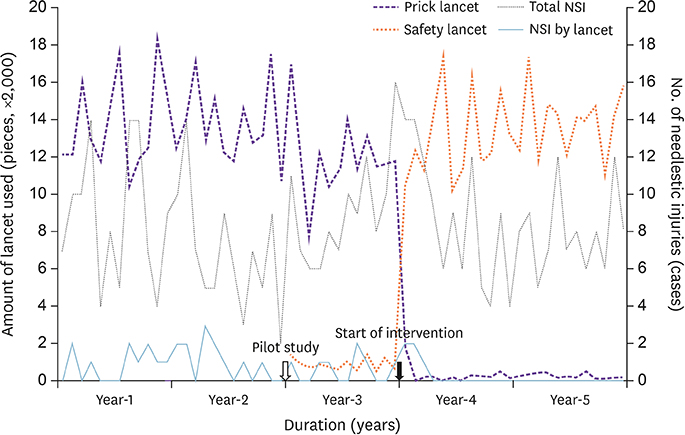

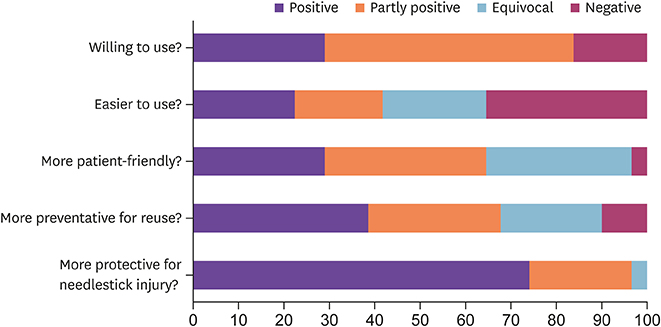

We implemented a SED lancet by replacing a conventional prick lancet in a tertiary hospital in a sequential approach. A spot test of the new SED was conducted for 1 month to check the acceptability in practice and a questionnaire survey was obtained from the healthcare workers (HCWs). A pilot implementation of the SED lancet in 2 wards was made for 1 year. Based on these preliminary interventions, a hospital-wide full implementation of the SED lancet was launched. The incidence of NSIs and cost expenditure before and after the intervention were compared.

RESULTS

There were 29 cases of conventional prick lancet-related NSIs for 3 years before the full implementation of SED lancet. The proportion of prick lancet-related NSIs among yearly all kinds of NSIs during two years before the pilot study was average 11.7% (22/188). Pre-interventional baseline incidence of all kinds of NSIs was 7.01 per 100 HCW-years. After the full implementation of SED lancet, the lancet-related NSIs became zero in the 2nd year (P = 0.001). The average direct cost of 18,393 US dollars (USD) per year from device and post-exposure medical care before the intervention rose to 20,701 USD in the 2nd year of the intervention. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was 210 USD per injury avoided.

CONCLUSION

The implementation of a SED lancet could eliminate the lancet-related NSIs to zero incidence. The cost increase incurred by the use of SED lancet was tolerable.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Green B, Griffiths EC. Psychiatric consequences of needlestick injury. Occup Med (Lond). 2013; 63:183–188.

Article2. Naghavi SH, Shabestari O, Alcolado J. Post-traumatic stress disorder in trainee doctors with previous needlestick injuries. Occup Med (Lond). 2013; 63:260–265.

Article3. Mannocci A, De Carli G, Di Bari V, Saulle R, Unim B, Nicolotti N, Carbonari L, Puro V, La Torre G. How much do needlestick injuries cost? A systematic review of the economic evaluations of needlestick and sharps injuries among healthcare personnel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016; 37:635–646.

Article4. Prüss-Ustün A, Rapiti E, Hutin Y. Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005; 48:482–490.

Article5. Cooke CE, Stephens JM. Clinical, economic, and humanistic burden of needlestick injuries in healthcare workers. Med Devices (Auckl). 2017; 10:225–235.

Article6. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO guideline on the use of safety-engineered syringes for intramuscular, intradermal and subcutaneous injections in health care settings. Accessed 01 February 2016. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250144/1/9789241549820-eng.pdf.7. Jagger J, Perry J, Gomaa A, Phillips EK. The impact of U.S. policies to protect healthcare workers from bloodborne pathogens: the critical role of safety-engineered devices. J Infect Public Health. 2008; 1:62–71.

Article8. Phillips EK, Conaway M, Parker G, Perry J, Jagger J. Issues in understanding the impact of the needlestick safety and prevention act on hospital sharps injuries. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013; 34:935–939.

Article9. Adams D, Elliott TS. Impact of safety needle devices on occupationally acquired needlestick injuries: a four-year prospective study. J Hosp Infect. 2006; 64:50–55.

Article10. Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA, Heneine W, Thomas V, Cheever LW, Gomaa A, Panlilio AL. US Public Health Service Working Group. Updated US Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013; 34:875–892.

Article11. U.S. Public Health Service. Updated U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001; 50:RR-11. 1–52.12. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Appendix B: Postexposure prophylaxis to prevent hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006; 55:RR-16. 30–31.13. Menezes JA, Bandeira CS, Quintana M, de Lima E Silva JC, Calvet GA, Brasil P, Brasil P. Impact of a single safety-engineered device on the occurrence of percutaneous injuries in a general hospital in Brazil. Am J Infect Control. 2014; 42:174–177.

Article14. Wu HC, Ho JJ, Lin MH, Chen CJ, Guo YL, Shiao JS. Incidence of percutaneous injury in Taiwan healthcare workers. Epidemiol Infect. 2015; 143:3308–3315.

Article15. Oh HS, Yi SE, Choe KW. Epidemiological characteristics of occupational blood exposures of healthcare workers in a university hospital in South Korea for 10 years. J Hosp Infect. 2005; 60:269–275.

Article16. Park S, Jeong I, Huh J, Yoon Y, Lee S, Choi C. Needlestick and sharps injuries in a tertiary hospital in the Republic of Korea. Am J Infect Control. 2008; 36:439–443.

Article17. Yun YH, Chung YK, Jeong JS, Jeong IS, Park ES, Yoon SW, Jin HY, Park JH, Han SH, Choi JH, Choi HR, Han MK, Choi SI. Epidemiological characteristics and scale for needlestick injury in some university hospital workers. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 2011; 23:371–378.

Article18. Lee JH, Cho J, Kim YJ, Im SH, Jang ES, Kim JW, Kim HB, Jeong SH. Occupational blood exposures in health care workers: incidence, characteristics, and transmission of bloodborne pathogens in South Korea. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17:827.

Article19. Elseviers MM, Arias-Guillén M, Gorke A, Arens HJ. Sharps injuries amongst healthcare workers: review of incidence, transmissions and costs. J Ren Care. 2014; 40:150–156.

Article20. Ministry of Employment and Labor. Occupational safety and health act, article 24. Accessed 1 February 2018. Available at: http://www.law.go.kr/engLsSc.do?menuId=0&p1=&subMenu=5&query=Occupational+safety+and+health+act&x=0&y=0#liBgcolor17.21. Ministry of Employment and Labor. Enforcement decree of the occupational safety and health act, article 597. Accessed 1 February 2018. Available at: http://www.law.go.kr/engLsSc.do?menuId=0&p1=&subMenu=5&query=Occupational+safety+and+health+act&x=0&y=0#liBgcolor0.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines: implementation and checklist development: a Korean translation

- A Comparative Study of Two Different Heel Lancet Devices for Blood Collection in Preterm Infants

- Comparison of Laser and Conventional Lancing Devices for Blood Glucose Measurement Conformance and Patient Satisfaction in Diabetes Mellitus

- Needlestick/Sharps Injuries in Nursing Students in Korea: A Descriptive Survey

- The Relationship between Job Stress and Needlestick Injury among Nurses at a University Hospital