J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2018 Sep;59(9):842-847. 10.3341/jkos.2018.59.9.842.

Cost-utility Analysis of Primary Open-angle Glaucoma according to Follow-up Observation Period

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, St. Vincent's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea. doj087@mail.catholic.ac.kr

- KMID: 2420332

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2018.59.9.842

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To evaluate the cost-utility based on the quantitative relationship between glaucoma follow-up and glaucoma progression.

METHODS

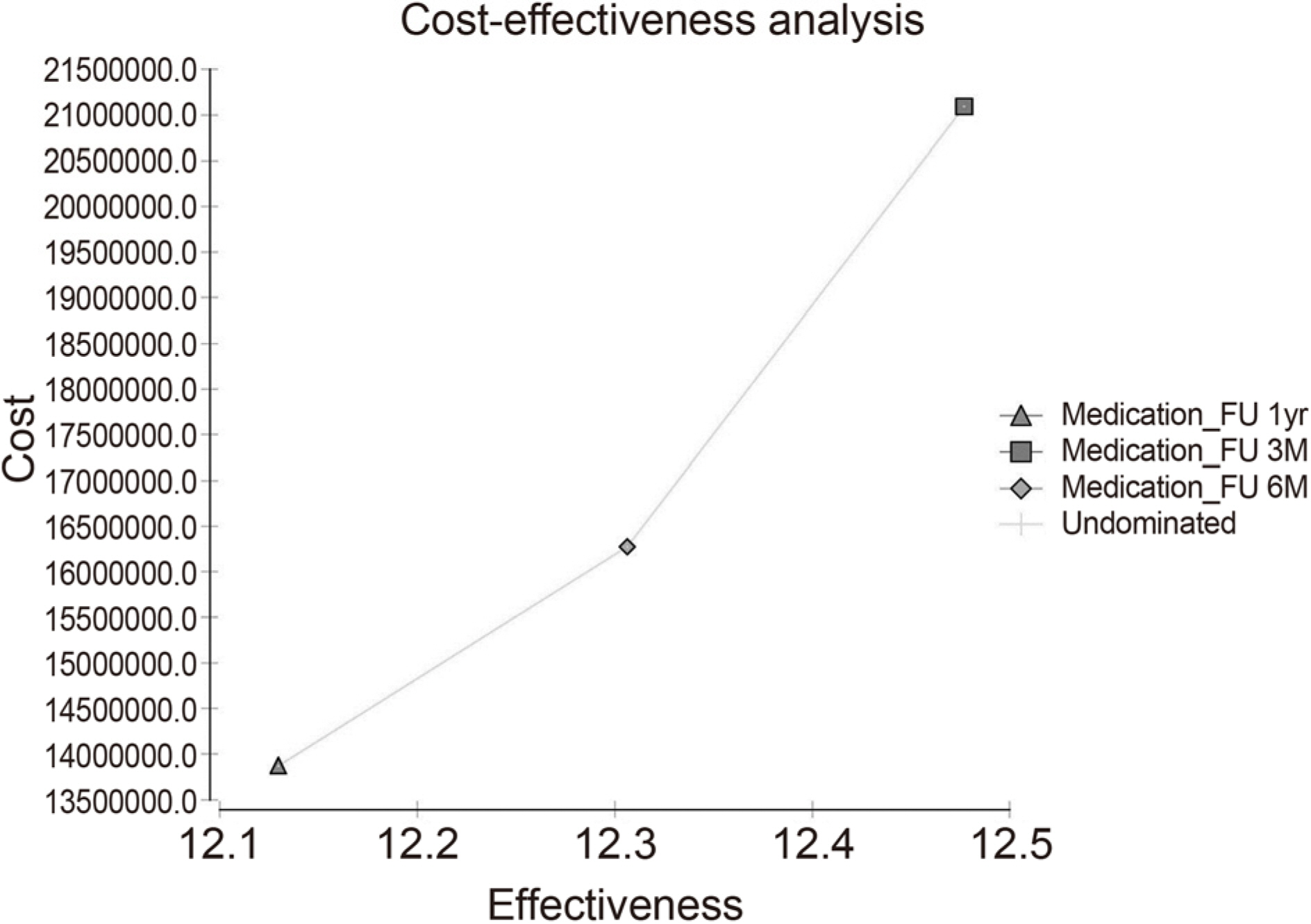

The Markov model was constructed and analyzed to determine the cost-effectiveness of primary open-angle glaucoma. The Markov model set up a virtual cohort of Korean over 40 years of age with early glaucoma. The costs associated with glaucoma treatment were assessed from a social point of view, and the utility was calculated using the quality adjusted life years according to the glaucoma states. Glaucoma health status was divided into 5 stages (early, middle, late, unilateral, bilateral blindness). The transition probability was set in one direction from mild to severe, and the length of each cycle was set at one year. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated and compared with each other different follow-up periods. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine how the uncertainty of the variables used in this study affected the outcome.

RESULTS

ICER of 3-month follow-up was 28,244,398 won/quality adjusted life years (QALY) compared 6-month follow-up, and ICER of 6-month follow-up was 13,615,443 won/QALY compared to 12-month follow-up. If the probability of progression of glaucoma in 6-months follow-up observations increases by more than 10% over 3-month periodic follow-up and the progression probability of 12-month follow-up increases by more than 15% follow-up compared to 3-months follow-up, 3-months follow-up was found to be a cost-effective strategy. On the other hand, 6-month follow-up was found to be cost-effective if probability of progression of 6-month follow-up was less than 10% increase of 3-month follow-up and 15% increase of 6-months follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Cost-effective follow-up strategies differed according to the probability of progression of glaucoma, and 3-month or 6-month follow-up strategies were cost-effective and acceptable in Korea's health care system.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Jonas JB, Aung T, Bourne RR, et al. Glaucoma. Lancet. 2017; 390:2183–93.

Article2. Levine RM, Yang A, Brahma V, Martone JF. Management of blood pressure in patients with glaucoma. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017; 19:109.

Article3. Stan C, Tîrziu D, Lupaş cu S. A new risk factor in glaucoma? Oftalmologia. 2011; 55:74–6.4. Jutley G, Luk SM, Dehabadi MH, Cordeiro MF. Management of glaucoma as a neurodegenerative disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2017; 7:157–72.

Article5. Bourne RRA, Jonas JB, Bron AM, et al. Prevalence and causes of vision loss in high-income countries and in Eastern and Central Europe in 2015: magnitude, temporal trends and projections. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018; 102:575–85.

Article6. Wang B, Congdon N, Bourne R, et al. Burden of vision loss abdominal with eye disease in China 1990–2020: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018; 102:220–4.7. Sung H, Shin HH, Baek Y, et al. The association between socioeconomic status and visual impairments among primary glaucoma: the results from Nationwide Korean National Health Insurance Cohort from 2004 to 2013. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017; 17:153.

Article8. Chan EW, Li X, Tham YC, et al. Glaucoma in Asia: regional prevalence variations and future projections. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016; 100:78–85.

Article9. Kim KE, Kim MJ, Park KH, et al. Prevalence, Awareness, and Risk Factors of Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008–2011. Ophthalmology. 2016; 123:532–41.10. Flaxman SR, Bourne RRA, Resnikoff S, et al. Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990–2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017; 5:e1221–e34.11. Rein DB. Vision problems are a leading source of modifiable health expenditures. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54:ORSF18–22.

Article12. Dirani M, Crowston JG, Taylor PS, et al. Economic impact of abdominal open-angle glaucoma in Australia. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011; 39:623–32.13. Ismail R, Azuara-Blanco A, Ramsay CR. Consensus on outcome measures for glaucoma effectiveness trials: results from a Delphi and nominal group technique approaches. J Glaucoma. 2016; 25:539–46.14. De Moraes CG, Liebmann JM, Levin LA. Detection and abdominal of clinically meaningful visual field progression in clinical trials for glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2017; 56:107–47.15. Vianna JR, Chauhan BC. How to detect progression in glaucoma. Prog Brain Res. 2015; 221:135–58.

Article16. Guedes RAP, Guedes VMP, Chaoubah A. Cost-effectiveness in glaucoma. concept result, and curent perspecitve. Revista Brasileira de Oftalmologia. 2016; 75:336–41.17. Rylander NR, Vold SD. Cost analysis of glaucoma medications. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008; 145:106–13.

Article18. Vold SD, Wiggins DA, Jackimiec J. Cost analysis of glaucoma medications. J Glaucoma. 2000; 9:150–3.

Article19. Stein JD, Kim DD, Peck WW, et al. Cost-effectiveness of medications compared with laser trabeculoplasty in patients with newly diagnosed open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012; 130:497–505.20. Motlagh BF. Medical therapy versus trabeculectomy in patients with open-angle glaucoma. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2016; 79:233–7.

Article21. Heijl A, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Leske MC. Natural history of open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2009; 116:2271–6.

Article22. Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Lee PP, et al. The cost-effectiveness of routine office-based identification and subsequent medical abdominal of primary open-angle glaucoma in the United States. Ophthalmology. 2009; 116:823–32.23. Paletta Guedes RA, Paletta Guedes VM, Freitas SM, Chaoubah A. Utility values for glaucoma in Brazil and their correlation with abdominal function. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014; 8:529–35.24. Saw SM, Gazzard G, Au Eong KG, et al. Utility values in Singapore Chinese adults with primary open-angle and primary abdominal-closure glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2005; 14:455–62.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Evaluation of Unilateral Open-Angle Glaucoma: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study

- Cost-Effectiveness of Early Surgical or Medical Therapy for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: A Decision Analytic Model

- IOP Change after Cataract Surgery in Patients with Controlled Chronic Glaucoma

- Significance of Peripapillary Atrophy in the Diagnosis of Open-angle Glaucoma

- Long-term Follow-up Results of Glaucoma Triple Procedures in Patients with Angle-closure Glaucoma