Yonsei Med J.

2017 Sep;58(5):934-943. 10.3349/ymj.2017.58.5.934.

Impact of Follow-Up Ischemia on Myocardial Perfusion Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Cardiology, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Seongnam, Korea.

- 2Division of Cardiology, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. mdyhkim@amc.seoul.kr

- 3Department of Applied Statistics, Gachon University, Seongnam, Korea.

- 4Department of Nuclear Medicine, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2418928

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2017.58.5.934

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Few studies have reported on predicting prognosis using myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) during coronary artery disease (CAD) treatment. Therefore, we aimed to assess the clinical implications of myocardial perfusion SPECT during follow-up for CAD treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

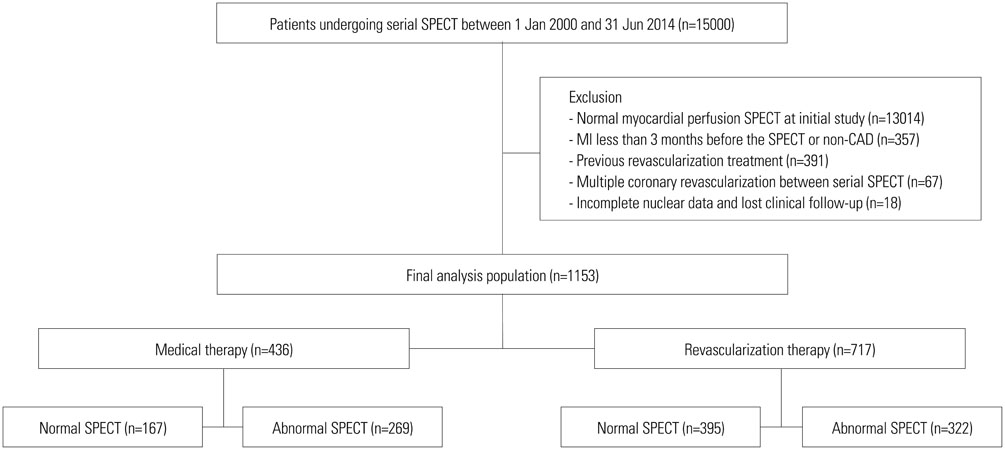

We enrolled 1153 patients who had abnormal results at index SPECT and underwent follow-up SPECT at intervals ≥6 months. Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) were compared in overall and 346 patient pairs after propensity-score (PS) matching.

RESULTS

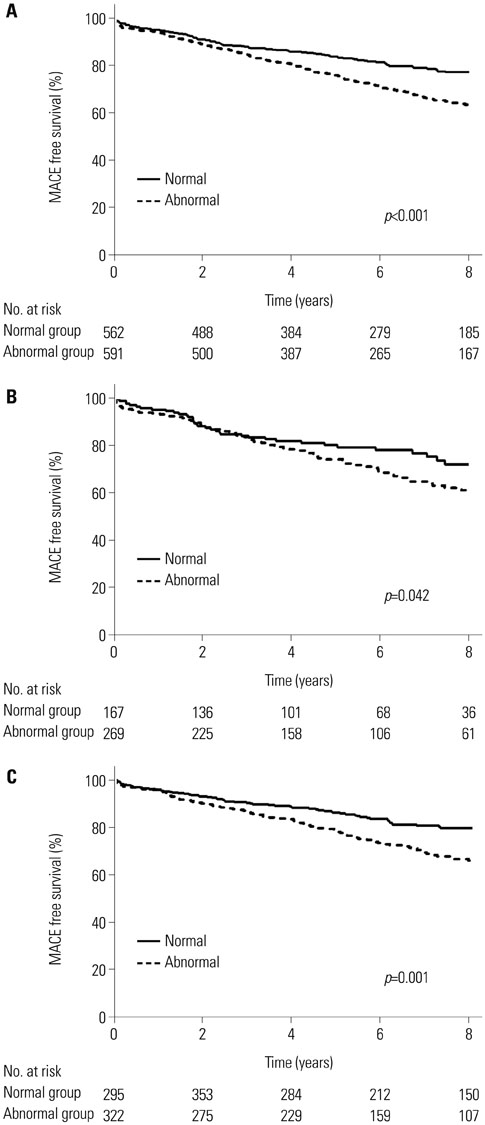

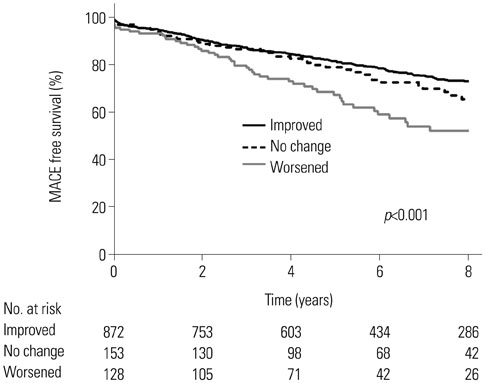

Abnormal SPECT was associated with a significantly higher risk of MACE in comparison with normal SPECT over the median of 6.3 years (32.3% vs. 19.8%; unadjusted p<0.001). After PS matching, abnormal SPECT posed a higher risk of MACE [32.1% vs. 19.1%; adjusted hazard ratio (HR)=1.73; 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.27-2.34; p<0.001] than normal SPECT. After PS matching, the risk of MACE was still higher in patients with abnormal follow-up SPECT in the revascularization group (30.2% vs. 17.9%; adjusted HR=1.73; 95% CI=1.15-2.59; p=0.008). Low ejection fraction [odds ratio (OR)=5.33; 95% CI=3.39-8.37; p<0.001] and medical treatment (OR=2.68; 95% CI=1.93-3.72; p<0.001) were independent clinical predictors of having an abnormal result on follow-up SPECT.

CONCLUSION

Abnormal follow-up SPECT appears to be associated with a high risk of MACE during CAD treatment. Follow-up SPECT may play a potential role in identifying patients at high cardiovascular risk.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Shaw LJ, Hage FG, Berman DS, Hachamovitch R, Iskandrian A. Prognosis in the era of comparative effectiveness research: where is nuclear cardiology now and where should it be? J Nucl Cardiol. 2012; 19:1026–1043.

Article2. Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Cohen I, Berman DS. Stress myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography is clinically effective and cost effective in risk stratification of patients with a high likelihood of coronary artery disease (CAD) but no known CAD. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 43:200–208.

Article3. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, Berra K, Blankenship JC, Dallas AP, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012; 126:e354–e471.4. Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico JA, Friedman J, et al. Exercise myocardial perfusion SPECT in patients without known coronary artery disease: incremental prognostic value and use in risk stratification. Circulation. 1996; 93:905–914.

Article5. Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Shaw LJ, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico JA, et al. Incremental prognostic value of myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography for the prediction of cardiac death: differential stratification for risk of cardiac death and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998; 97:535–543.

Article6. Farzaneh-Far A, Borges-Neto S. Ischemic burden, treatment allocation, and outcomes in stable coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011; 4:746–753.

Article7. Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Cohen I, Berman DS. Comparison of the short-term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003; 107:2900–2907.

Article8. Hachamovitch R, Rozanski A, Hayes SW, Thomson LE, Germano G, Friedman JD, et al. Predicting therapeutic benefit from myocardial revascularization procedures: are measurements of both resting left ventricular ejection fraction and stress-induced myocardial ischemia necessary? J Nucl Cardiol. 2006; 13:768–778.

Article9. Dagenais GR, Lu J, Faxon DP, Bogaty P, Adler D, Fuentes F, et al. Prognostic impact of the presence and absence of angina on mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and stable coronary artery disease: results from the BARI 2D (Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:702–711.

Article10. Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, Mancini GB, Hayes SW, Hartigan PM, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the clinical outcomes utilizing revascularization and aggressive drug evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008; 117:1283–1291.11. Zellweger MJ, Fahrni G, Ritter M, Jeger RV, Wild D, Buser P, et al. Prognostic value of “routine” cardiac stress imaging 5 years after percutaneous coronary intervention: the prospective long-term observational BASKET (Basel Stent Kosteneffektivitäts Trial) LATE IMAGING study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014; 7:615–621.

Article12. Schepis T, Benz K, Haldemann A, Kaufmann PA, Schmidhauser C, Frielingsdorf J. Prognostic value of stress-gated 99m-technetium SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging: risk stratification of patients with multivessel coronary artery disease and prior coronary revascularization. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013; 20:755–762.

Article13. Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D, Buszman P, Camici PG, Crea F, et al. Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris: executive summary: the task force on the management of stable angina pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:1341–1381.

Article14. Hendel RC, Berman DS, Di Carli MF, Heidenreich PA, Henkin RE, Pellikka PA, et al. ACCF/ASNC/ACR/AHA/ASE/SCCT/SCMR/SNM 2009 appropriate use criteria for cardiac radionuclide imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53:2201–2229.15. Zellweger MJ, Kaiser C, Jeger R, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Buser P, Bader F, et al. Coronary artery disease progression late after successful stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 59:793–799.

Article16. Kim YH, Ahn JM, Park DW, Song HG, Lee JY, Kim WJ, et al. Impact of ischemia-guided revascularization with myocardial perfusion imaging for patients with multivessel coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60:181–190.

Article17. Aepfelbacher FC, Johnson RB, Schwartz JG, Chen L, Parker RA, Parker JA, et al. Validation of a model of left ventricular segmentation for interpretation of SPET myocardial perfusion images. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001; 28:1624–1629.

Article18. Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, et al. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002; 105:539–542.

Article19. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011; 124:2574–2609.

Article20. Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, Bittl JA, Bridges CR, Byrne JG, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011; 124:e652–e735.21. Ho D, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Softw. 2011; 42:1–28.22. Mahmarian JJ, Dakik HA, Filipchuk NG, Shaw LJ, Iskander SS, Ruddy TD, et al. An initial strategy of intensive medical therapy is comparable to that of coronary revascularization for suppression of scintigraphic ischemia in high-risk but stable survivors of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48:2458–2467.

Article23. Dakik HA, Kleiman NS, Farmer JA, He ZX, Wendt JA, Pratt CM, et al. Intensive medical therapy versus coronary angioplasty for suppression of myocardial ischemia in survivors of acute myocardial infarction: a prospective, randomized pilot study. Circulation. 1998; 98:2017–2023.

Article24. Schwartz RG, Pearson TA, Kalaria VG, Mackin ML, Williford DJ, Awasthi A, et al. Prospective serial evaluation of myocardial perfusion and lipids during the first six months of pravastatin therapy: coronary artery disease regression single photon emission computed tomography monitoring trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 42:600–610.

Article25. Klocke FJ, Baird MG, Lorell BH, Bateman TM, Messer JV, Berman DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ASNC guidelines for the clinical use of cardiac radionuclide imaging--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASNC Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Clinical Use of Cardiac Radionuclide Imaging). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 42:1318–1333.

Article26. Farzaneh-Far A, Phillips HR, Shaw LK, Starr AZ, Fiuzat M, O'Connor CM, et al. Ischemia change in stable coronary artery disease is an independent predictor of death and myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012; 5:715–724.

Article27. Zellweger MJ, Hachamovitch R, Kang X, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Germano G, et al. Threshold, incidence, and predictors of prognostically high-risk silent ischemia in asymptomatic patients without prior diagnosis of coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2009; 16:193–200.

Article28. Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, Daley J, Deedwania PC, Douglas JS, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina--summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 41:159–168.

Article29. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 128:1810–1852.

Article30. McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:1787–1847.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Correlation Between Functional Myocardial Perfusion Imaging and Anatomical Cardiac CT in a Case of Myocardial Bridging

- Comparison of Silent Patients with Painful Patients in Patients with Coronary Artery Stenoses during Exercise Myocardial Perfusion Scintigraphy

- Diagnosis of Coronary Artery Disease Using Myocardial Perfusion SPECT

- Assessment of Myocardial Ischemia Using Stress Perfusion Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance

- Post-Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Myocardial Ischemia Caused by an Overgrown Left Internal Thoracic Artery Side Branch